Hoarding at the End of the World

Eurogamer's Rich Stanton explores how The Last of Us works for The Most of Us.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

While playing and after finishing The Last of Us, all I could think about was a book.

When Naughty Dog began development Amazon must have seen a miniature sales spike for Cormac McCarthy's The Road; the mind's eye imagines a bulk order from California, and subsequent rows of well-thumbed paperbacks.

This is a great thing! Video games are wedded to the idea of dystopias anyway, and I'd much rather have one influenced by The Road than Fallout. What is interesting are the aspects of this world The Last of Us absorbs, and those it decides to leave behind -- choices driven by a clear-eyed focus on what a video game 'should' offer its players.

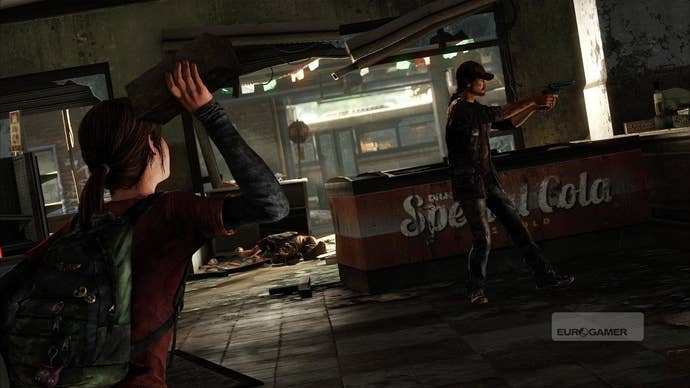

The most obvious example is everywhere: stuff. Rags, nails, blades, scrap metal, candy, bullets, tape, booze, toolkits, sugar, and comics. Scarcity of resources in The Last of Us is something that was emphasized by its developers pre-release, and is driven home by a narrative filled with examples -- rations, the Hunters that strip unwary travellers of their possessions, and the little hunting cameo. Except in practice this world is abundant, something exemplified in the multiple sweeping animations of Joel's hypnotic hands. I find his occasional comments on this good luck pretty funny, because they always remind me of CJ in San Andreas saying "I'll ha' that."

Because I love you all I'm going to type out a short section from The Road; for those who haven't read it, the book tells the story of a father and his son in a desolate post-crisis society. In this extract, after fruitlessly searching an old supermarket, the father finds something.

By the door were two softdrink machines that had been tilted over into the floor and opened with a prybar. Coins everywhere in the ash. He sat and ran his hand around in the works of the gutted machines and in the second one it closed over a cold metal cylinder. He withdrew his hand slowly and sat looking at a Coca Cola.

What is it, Papa?

It's a treat. For you.

What is it?

Here. Sit down.

He slipped the boy's knapsack straps loose and set the pack on the floor behind him and he put his thumbnail under the aluminium clip on the top of the can and opened it. He leaned his nose to the slight fizz coming from the can and then handed it to the boy. Go ahead, he said.

The boy took the can. It's bubbly, he said.

Go ahead.

He looked at his father and then tilted the can and drank. He sat there thinking about it. It's really good, he said.

Yes. It is.

You have some, Papa.

I want you to drink it.

You have some.

He took the can and sipped it and handed it back. You drink it, he said. Let's just sit here.

It's because I wont ever get to drink another one, isn't it?

Ever's a long time.

Okay, the boy said.

I wish every critic who praised The Last of Us' world building had to spend a week reading that over and over again. It communicates scarcity using capitalism's biggest and brightest emblem -- but look at what else we can glean along the way. Currency is worthless. Places like supermarkets have long since been picked clean. The boy is suspicious of bubbles, so has never seen a soft drink. And the father's tenderness is palpable -- not least in that half-conscious echo of Peter Pan at the end. "Forever is an awfully long time."

That unfamiliar sense of awe you're feeling is because McCarthy has created a universe in a few paragraphs. Even though a can of Coca Cola is a common object, we understand that in this world it is something very special -- a treat. My intention is not to boot The Last of Us for imitating aspects of The Road then being unable to match them; comparing the characterization of the boy to Ellie, for example, may be unfavorable to The Last of Us but it's not a straight comparison. Rather it's to think about why The Last of Us' world, in the eyes of its creators at least, had to incorporate so many mechanics and things at the expense of its setting. And why the cost of making games like this, and I mean that literally, is both creator and destroyer.

During my playthrough (on Hard) I frequently had too much stuff to actually carry. Rags, blades and bottles were overflowing from Joel's backpack -- so I'd combine what I could to make space, and go on. By the latter half of the game I had so much stuff like molotovs I'd deliberately use them during engagements just to pre-emptively clear inventory space. This is the opposite of scarcity -- a direct contradiction to what we're told about the setting.

So we have mechanics that oppose the world's narrative. But it's when you combine this with the guns that The Last of Us really rips free of the fiction -- as it establishes in its very first piece of post-apocalypse scene-setting, guns are a valuable commodity indeed. So rare, in fact, they're Joel's initial reason for taking on this dangerous escort mission.

The truth is that by the end of the game he wouldn't need them anyway. In one of the final sequences, when Ellie is in trouble, as Joel you approach the building where she is. You've got a shotgun, a sniper, a shotgun pistol, a revolver, molotovs, grenades, smoke bombs, and plenty more stuff in your backpack. You feel like f***ing RAMBO. Welcome to the end of the world!

Now rather than criticizing The Last of Us for this, which is an open goal, think about why it's like this. There's accumulation: you only gain guns, never lose them. Then there's the wealth of ammunition. Then there's the fact that The Last of Us has a crude but very effective formula underpinning its status as an original title: if players don't like the sneaking around, they can play it like any other third-person shooter.

This is crucial and the beginnings of a wider point: Naughty Dog don't make niche titles, they make mainstream hits. This means that the studio cannot even risk alienating the dumb shooter portion of the audience. More than that, it means that The Last of Us is a game that has negative space instead of rough edges -- every surface is smoothed-down and anything that could potentially annoy or inconvenience players has been mitigated. These are the fruits of an incredible dedication to playtesting and responding to audience feedback. It also unfortunately makes it near-impossible to challenge your audience beyond certain very well-defined limits. So for example, The Last of Us' structure of fights-then-downtime soon becomes so predictable that it helps create the impression of abundance -- because there's no point in conserving anything when you're guaranteed a bonanza of items after nearly every fight.

The Last of Us is really, rather than a grim end-of-the-world tale, a lavish action extravaganza. Why is this important? Every single item in the game, and its interactions, demands a sizeable commitment of resources -- which means it is not literally but practically impossible for Naughty Dog to, for example, create a shotgun and give you only two shells to last the whole game. Think about that; imagine they'd made a game where ammunition actually was scarce, where choosing to shoot a gun was actually a decision rather than a reflex.

This is kind of funny, right? The Last of Us' weaponry is collectively a superb piece of engineering -- perfect exponents of what the critic Marsh Davies explains as 'Gunfeel.' And because of that level of craft and polish, and the time it must have taken, Naughty Dog simply cannot afford to use them as scarce one-offs. It can't give the weapons any value in-game because it has to get the studio's money's worth out of these assets.

And it's this that puts players in an invidious position. There's a dull itch at the back of your brain during The Last Of Us that's hard to place: what's not quite right here? And the answer is that everything's right.

All corners are sanded-down, and all of the rough edges are long since removed. This approach comes with a hidden cost, which is that by concentrating on keeping players within an interactive comfort zone, through an over-abundance of munitions and health packs, those same players are constantly reminded that the world is window-dressing. Nothing's precious if there's too much of it, and if your central theme is scarcity this changes from a balance issue into simple self-contradiction.

I've always thought that the cutscene-heavy approach towards action games exemplified by Naughty Dog's Uncharted series is a dead end, because it's more of a refusal to engage with interactive narrative than any kind of a solution. Eurogamer's Tom Bramwell made a great argument for why you shouldn't see the game in quite these terms but for me the similarities in method are much larger than the differences. And so I'd say The Last of Us actually stands as the best example of that approach ever made -- the great mistake.

That's why for me The Last of Us is ultimately ephemeral rather than memorable. I wasn't interested in playing through it again. It just went back on the shelf -- worth the £40, I'd say, but the more you digest it the less convincing it becomes as a whole . The saddest thing is that for all the care and work that's gone into the game, it's all been in the wrong places -- or, at least, the most superficial ones. You can cut this game's atmosphere with a knife -- and then blow away everything with big guns. I suppose that's the price you pay for working at the top.