He’s Getting a Fireball: Josh Sawyer Reflects on Nearly 20 Years Spent Making RPG Classics for Obsidian and Black Isle Studios

Obsidian’s veteran RPG designer talks about getting into the industry, working on some of the best RPGs ever, and what he does to monologuing villains.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

It's a quiet Wednesday morning; and in what has become a regular ritual for the Obsidian office, Josh Sawyer has brought bagels for the team. He enjoys it because it brings him back to college, where it was much easier to bike around than in Irvine.

Soft-spoken and yet loquacious, Sawyer will rarely speak until a topic piques his interest, at which point he will hold forth for seemingly minutes at a time. And as it happens, quite a few topics pique his interest: fencing, history, tattoos. At one point he even attended the Lawrence Conservatory of Music for vocal performance (he quickly switched to history).

But what Sawyer is best-known for is RPG design, which is why he's been at Obsidian-and before that, Black Isle Studios-for more than a decade. Sawyer has worked on some of the best-loved RPGs around, and he brings the same laser-focused intensity to his work as a designer that he does to his conversations.

I recently sat down with Sawyer to discuss his nearly 20 year journey through the industry, which has taken him from a small town in Wisconsin, through the collapse of Black Isle Studios, and into Obsidian, where he is currently working on Pillars of Eternity II: Deadfire. Below you can find his reflections on his successes and failures, the challenges he's faced through his career, and most importantly, why he's prone to throwing fireballs in the faces of monologuing villains.

Origin Story

Josh Sawyer grew up in a small town in Wisconsin. An introverted, artistic kid, he mainly gravitated toward games as his outlet. Dungeons& Dragons were where he found friends, and also an understanding of how games really worked.

You grew up in Wisconsin in kind of a small town. Is that fair to say?

Josh Sawyer:: Yeah. It's Fort Atkinson which, when I was growing up I think it was 10,000, now I think it's 11, maybe 12,000 people. Yeah, it's very typical of a Wisconsin town. There are lots of 10,000 population towns all over Wisconsin. Now my family lives in a little teeny town of like 2,000 people. It's technically like a village, I guess.

It was a pretty typical sort of upbringing. We moved around a lot but usually lived in farmhouses in the countryside and just went to public schools.

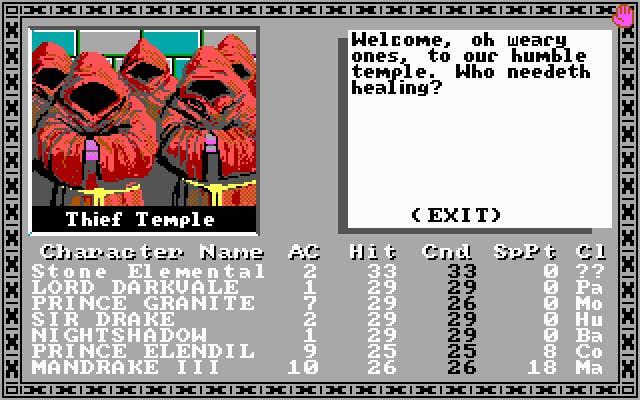

The Bard's Tale was the first CRPG that you saw.

JS: Yeah. That was pretty weird. I actually started playing D&D before I really knew about CRPGs. My family didn't really have a lot of money growing up and so having a computer was not really a thing, especially since computers were relatively expensive back then, but we had a really nice public library. I went to the public library with a few of my friends and I saw this older kid on a Commodore 64 playing something and I was like, "What in the world am I looking at?" It was Bard's Tale and it was incredible to me.

This older kid, Tony, he was actually pretty nice. He was, I want to say like six, maybe eight years older than me, but he was pretty nice to me considering I was a little kid and he was in high school. He told me all about it and I said, "Oh yeah, we play D&D." He was like, "Oh, what do you play," and I was like, "Oh, I play Expert with my friend Ryan." He was like, "Oh, me and my friends play Advanced," and I was like, "I don't even know what that is!"

I started playing Advanced Dungeons & Dragons with Tony and his friends. It's a small town so there was lots of connections between, like so one of Tony's friends who played in the game was the son of the guy who owned the pizza joint where everyone went after the football games.

It was pretty cool. It was sort of a way for me for me to socialize, because I grew up in the countryside and I wasn't super social and because we moved around a lot. I didn't have a ton of close friends but I knew a lot of people. Like when I went to high school, I knew almost everyone because I had gone to every public school in the area and I had played basketball with the kids from the parochial schools as well, but I didn't really have close friends. D&D was one of the ways where I finally started to get friends that were more than just kind of superficial, more than acquaintances, I guess.

I'm not a designer by any means, but I used to make missions and that kind of thing. I would also play the occasional tabletop game, and it did get me thinking in kind of game design terms. Was that the same for you?

JS: Yeah, very much so. I started thinking like, "I don't really like how these rules encourage this behavior or how these rules discourage this a cool and fun behavior." Or, "I don't really understand what this rule accomplishes, like why is this rule here? What good does it do?" That's when I started just modifying rules, just sort of saying to the players, "Hey, I'm going to change this. Does anyone really care?" Sometimes they cared, most of the time they were like, "No, that's fine." Sometimes it was to their benefit and so they were like, "Oh great, sure, change whatever you want.

Then in college, I played a lot more tabletop games. Played GURPS, played Vampire, played Legend of the Five Rings, played a lot of this stuff and so I was getting exposure to different mechanics that were just fundamentally really different from AD&D's. Then I started thinking, "Oh, okay, so this is another way that you can do things and this is what this accomplishes and this is what this really doesn't accomplish," or, "These are the problems that arise in something like Shadowrun." People joke about rolling 20 six-sided dice to do things.

Also, a friend and a classmate of mine, Jer Strandberg, was designing his own roleplaying game and he wanted playtesters. I signed up to just break the rules. I would be the guy who said, "Hey Jer, you know if you do this then you can basically break the game," and he's like, "I don't think that's true," and I'm like, "Here we go, my friend." I'd start building the characters. "Okay, okay, okay, you proved the point, you proved the point!" It wasn't to do anything malicious, it was literally to help him. I said, "There is a structural problem here."

College was when I started developing my own tabletop roleplaying game and playing with my friends. I ran a campaign for a few years and that was really complicated, but it also showed because in my mind, being a young amateur game designer, I was like, "Oh, I want to simulate things more, I want it to be more realistic." But in doing that I also saw, "Oh, this can really slow the game down, there are drawbacks to doing this."

I think that's when I started to understand that design is less about coming up with a perfect decision. Like, "Oh, this is the perfect answer to the problem." It's more about what compromises you are willing to deal with, because there are really tradeoffs to almost any decision you can make. There are people that you're going to make happy, people who are not going to be happy, things that you're going to accomplish, things that you're not going to accomplish, things that you're going to cause to happen that are negative, but you have to weigh them against, "Well, that's a negative, but I think that overall accomplishes something good, so I'm willing to accept that."

Even as an amateur designer I was starting to get a picture of design as about deciding what you want to do. Like fundamentally at a high level, "What am I trying to accomplish with these rules, these characters, these systems," and then thinking about, "Okay, if this what I'm trying to do, how can I get there?" Constantly reevaluating and saying, "Am I still really getting to where I want to go or have I gone astray?" That helps redirect me into hopefully something better.

Who was your favorite character?

JS: The character that I really liked in college was a holy strategist of the Red Knight, so she was a cleric of the goddess of strategy and tactics. That was the character I made for the Second Edition campaign because it kind of allowed me to metagame in character, like I could have a character who was min-maxing because that was her point.

She was a little non-traditional in a few ways. She was physically not very strong, which as a cleric can be a liability in Second Edition because you kind of expect them to do a little bit of melee fighting, but she had an 18 in intelligence, which is not really an asset for a cleric but that's the character that I wanted to play. As this super intelligent priest of tactics, she was pretty wise and sort of charismatic. But she was also ruthless, always thinking about how she could get the drop on people, how people could get the drop on them and really pragmatic.

The party got this magic item called the Medegian Bracelet of Lost Ships and we got a Helm of Underwater Action, and so we used those to find a sunken Calishite war galley I think that had sunk off of the Sword Coast. We were like, "God, how are we going to get this thing out of here?" She was like, "Okay, I've got a plan."

We went to the Priests of Lathander in, I think it was Lathtarl's Lantern on the Sword Coast. We were like, "Hey, we will make a big donation to your church. We know that you have the spell Rosemantle that can be used to repair damage to things. Would you come out with us to the ocean and help us fix this ship?" They're like, "What? Okay, I guess that's fine."

We went out there and we used the Medegian Bracelet of Lost Ships. We had our ranger put on the Helm of Underwater Action and go around down below and scout it out. We brought it up and the Priests of Lathander, they patched the ship up. They were like, "How are you going to get this thing back to shore?" I was like, "Oh, we got some ways to take care of that. Here's the donation, see you guys later," and they went back to shore.

Then my character animated all the dead sailors and had them sail the ship back. When they got into port, the Priests of Lathander were like, "What are you doing?" Because it's a bunch of undead. She was like, "What's the big deal?" She dismissed them all. She was like, "It doesn't matter. They're all resting now. It's no big deal."

That was a really fun character to play, just in part because she was kind of against type. She wasn't physically strong, she wasn't actually super wise, but she was very smart. And being able to metagame or min-max in character was pretty fun.

What was the eureka moment that made you go, "Yes, I want to work in games"?

JS: I always thought I was going to work on tabletop games. I think it was in high school. I don't think there was a eureka moment, I think I started to realize, "Hey, you can just make rules." This is something I sort of tell people all the time, like, "You know, roleplaying games a lot of times in the books will say, 'Hey, you're free to change any of these rules.'" But a lot of people feel very paralyzed, they don't really do it. I'm like, "No, no, you can just do whatever you want." There are going to be consequences to I,t but you can just get rid of a rule, you can change a rule, you can do whatever you want. You can sit down and you can write all your own rules for you and your friends. You don't even have to write all of them, you just have to write the rules that you need and that's enough.

When I started realized you could do that, I felt like almost anyone could do this. Like they wouldn't necessarily do it well, but I think I could do a pretty good job of it. That's when I started thinking, "I think I want to be a tabletop game designer." I had no idea how in the world I was going to do that. I had no idea how that industry even worked even though my dad had worked with TSR and with TSR artists and all this other stuff, but that was in my mind. I was like, "Oh yeah, I'm going to be a tabletop game designer."

It was just luck that wound up getting me a job at Black Isle working on computer roleplaying games that happened to be based on tabletop roleplaying games. It was just incredible lucky, really, that I wound up in the game industry at all.

Black Isle Studios

Josh Sawyer applied to Black Isle Studios as a web designer and was ultimately hired after the first choice moved to Seattle. Soon, Sawyer was a junior designer working on Ice Wind Dale.

Can you paint a picture of what Black Isle was like back in those days?

JS: Coming to Black Isle, it was lots of dudes, lots of young dudes mostly. There were some people that had been in the industry there for quite a while, some of whom still work here at Obsidian.

Icewind Dale was interesting because we had no leads. It was almost entirely juniors, so it was a bunch of junior designers. Some of them had worked on Torment, but they were still juniors.

That was when I lived very close to work in Irvine. I lived with a coworker, Jacob Devore, who was a programmer at Black Isle, and we went to work pretty much every day. I didn't really have a life outside of work. Part of that was because the school has a very compact campus. Everyone was required to live on campus and you don't really need a car. It was very hard for me to think outside of just waking up, going to work, doing a bunch of stuff, playing Tribes--I played a lot of Tribes--and then coming home.

It was a little more stressful than Obsidian in a lot of ways. There were more personality problems to manage, I think in part because there were so many us who were very young and inexperienced and we were just brats and professionalism was not a thing that we really understood. If we got into arguments, they could just be big, stupid arguments. For the most part, though, surprisingly we got along on stuff.

It was a bunch of people just trying stuff. For me, from my perspective, I think Colin McComb recognized pretty early that I knew the Forgotten Realms and Dungeons& Dragons really, really thoroughly, and so I was the person on the team who was the most driven to get all the Forgotten Realms elements in, to get all the rules as close as possible.

One of the things that always bugged me, because Baldur's Gate came out before I came to Black Isle and I was really irritated that none of the racial bonuses were implemented. So as soon as I got onto Icewind Dale I'm like, "Okay, we're implementing all these racial bonuses. Elves get resistance to Sleep and Charm," and so on. I was the person who was really into all the lore stuff and trying to get all that really accurate.

I remember people loved working on games. Maybe not every single person, but overall the feeling was that people wanted to work hard. We never had required overtime, but people were there all the time because they just wanted to make cool games, and so we just wanted to be at work doing that, and we were in our 20s.

Was Colin McComb kind of a mentor?

JS: I wouldn't necessarily say that. It's kind of weird. One of the things that's sort of unfortunate is that, I mean I respect Colin a lot, don't get me wrong, but the Icewind Dale project was a bunch of juniors without leads. Colin gave feedback, Colin came up with the name of Yxunomei because I was like, "Okay Colin, you come up with goofy fantasy names. Give me something with Xs or Zs in it or some apostrophes." Chris Avellone gave feedback and he eventually wound up writing some characters and things like that, but they had other stuff to work on.

It was sort of a weird environment where there wasn't formal mentoring. We sort of learned things as we went along. We got feedback from the more senior designers, but it was just less structured, I think, than a lot of companies are in terms of a junior comes on and they're immediately put with a senior person or a lead to help guide them. But that really wasn't the vibe at Black Isle. It was kind of, "Make stuff! Talk to each other! Figure out how to make more stuff!"

Any particular hard lessons or things that you learned from Icewind Dale where you were like, "Oh, don't do that again?"

JS: Oh, there was tons of stuff that was not good. There was lots of stuff about level design. I started as an area designer even though I was doing a lot of system design as well. But things about level flow and layout, the fact that Dragon's Eye was five levels deep and had no backdoor to get out of so you had to march all the way back out to the top.

I did learn some good things, I think, in Dragon's Eye even though it didn't make necessarily great sense. There were some good things I wound up doing there in terms of varying the enemies that you fought so that as you go from level to level to level you feel like, "Oh wow." Not necessarily that each encounter is new, but that each level is certainly new.

There were certain other things that I did, like not randomizing unique items that people rely on for their build. Also making sure that everything that you can specialize in as a weapon is represented in the game by a unique item, so if someone says, "I'm going to be a short bow specialist," there should be a weapon that's better than +1 Short Bow in the game.

There's just a lot of things to think about, and a lot of this came out in the feedback where people were like, "What the hell, I made this character and I was hoping to get this mace, but that mace is randomized, so on my playthrough I never found it."

I thought it would be cool, sort of like tabletop. Like, sometimes you find the thing you want and sometimes you don't. When a person is investing that amount of time into a CRPG, though, they just get more aggravated.

A lot of people associate you closely with Chris. Is it fair to say that you guys had a really close working relationship, and how did that mature and grow over time?

JS: It changed from time to time. On some projects we worked closely together, on some projects we didn't work on at all. Certainly Chris is really fundamentally responsible for how we wrote dialogue at Black Isle. Colin was also a huge influence on that. As we came over to Obsidian, Chris was the driving force behind, like these are the standards for how we write things, how we format things, and he was always very quick to give constructive feedback on story elements, character development, things like that.

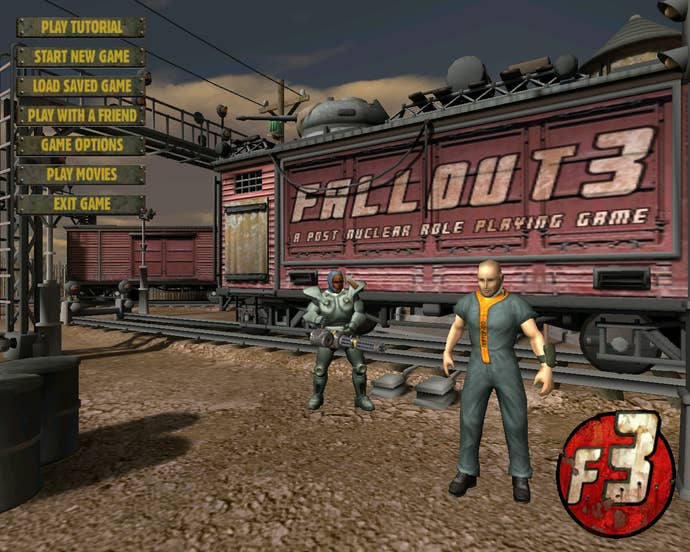

Our paths sort of crossed at various places. On Icewind Dale, he wound up writing a few characters, and then in Heart of Winter he wrote a few additional characters, but it wasn't like a very close working relationship. Then on Fallout 3 he was the lead designer and I was the lead systems guy. We worked closer on that because Chris had the Fallout bible that he had written, and so I was trying to help focus. Like, "Okay, is there a single story in here that we can take and actually move forward with," because he had an incredible range of ideas.

The other thing that Chris did was he ran a Fallout tabletop game based on the computer mechanics at Black Isle, and so I was one of the people playing in his campaign there. Then at Obsidian, the games that we worked most closely on were Fallout: New Vegas. Chris was not super involved on the core of Fallout: New Vegas. He worked a little bit with me and with John Gonzales on cleaning up the story and certain character things, in part because John Gonzales, who's a great writer, was not used to writing branching narratives and stuff like that, so Chris and I worked a lot with John to evolve that.

Chris wrote Cass, one of the companions. Then as the main game wrapped up, Chris was the director on Dead Money, on Old World Blues and Lonesome Road. I was the director on Honest Hearts and Gun Runner's Arsenal. Although Gun Runner's Arsenal didn't really have anything to do with the rest of the stuff, Chris and I had to collaborate a lot to make sure that the DLCs actually fit together with Fallout: New Vegas and the core game. He had a certain progression towards Ulysses in mind, and Honest Hearts needed to fit into that progression.

What was the number one thing that you learned from working with Chris Avellone?

JS: I would say it's thinking about what the player wants to do. There's pictures of Chris around the office with a speech bubble that says, "Can I make a speech check here? Because I really want to make a speech check."

The idea is like if a NPC says something, imagine if you're sitting at a table. You have to write the possibilities of what the player can say. If an NPC is a jerk, think about, "Okay, well how is a player going to want to respond? How are different players going to want to respond? Is the player going to want to slap this character? Is the player going to want to take the high ground and be above it all? Are they going to be quiet and just accept it? Or are they going to want to do something else?" Also like, "Oh, if there's a quest that presents this thing, does that sort of beg, 'Oh, I'm a character with these skills and that makes me want to do these things?'"

He was always the guy who was pushing for us as designers to find ways to respond. Not only to give players opportunities to slap the guy who makes fun of you, but also saying, "Hey, if you have this skill in the game, if you have electronics in the game, you have to find ways to bring electronics to the surface and let a character who specializes in electronics feel like they are a cool character." He reinforced that a lot.

Sometimes when we would play through games, he would make a character with an odd build that would seem kind of unusual and he would say, "Why can't I use these things," which is a good point. Again, if you make a character that's built in a certain way, if the player doesn't have some opportunity to really shine and go, "Ah yes, finally, all those points I put into doctor make me feel like I'm really cool," then that sucks. It feels like a huge letdown.

Black Isle obviously produced some of the best CRPGs ever. Planescape: Torment, Fallout. What was the secret?

JS: do think that the huge focus on really trying to let players define who they were and express that and have the world respond to it instead of just boxing them in. Instead of the designer saying, "This is my story and you're here to go through it," you're saying, "Here is a story, here is part of a story, here's half of a story, and here is a space where you decide how the other half comes into this."

It's saying that when you, I think back to, I'll pick on one of my DMs from high school. I won't name him, but he had this tendency to read big chunks of block text, like soliloquies from villains. It gets kind of boring. He had this wizard come down these stairs, actually I think it was a lich or something, and he started reading this box text and he started to talk and I'm like, "Hey dude, fireball." He's like, "What?" I'm like, "That guy's getting a fireball." He's like, "Oh, but he just started talking." I'm like, "He's getting a fireball."

He was really upset and I'm like, "I'm not going to listen to this guy. This dude has been tormenting us. He's screwed with us. He yanked us off our ship. I don't want to hear what he has to say. I want to throw a fireball at him," and so he's like, "Okay." And so I f*cking just blew this dude up with a fireball!

I think about that and I think about other DMs who try to bend over backwards to make the player go on their story. That's not why people really play those games. When I listen to people talk about their favorite roleplaying game experiences, I'm talking about tabletop, they're not talking about the DM's story. That's not what people talk about. That's literally never what people talk about. They talk about, "Dude, we got in this thing, and I smacked this guy, and then they called the guards, and then I jumped out the window and my character broke their leg, and then..." It's like all this sort of side stuff where they improvise and they do the unexpected thing and they just lash out and act crazy, and the DM goes like, "Okay."

The good DMs, they just roll with it. They create a world that doesn't punish the player for doing what they want, but responds believably. Yeah, if you smack the mayor with a bunch of guards standing around with spears, they're probably going to come after you, but if you murder someone in the middle of nowhere where no one can see it, maybe you get away with that.

[H]e started to talk and I'm like, "Hey dude, fireball." He's like, "What?" I'm like, "That guy's getting a fireball."

I think that with Fallout, for me it was really amazing in college to play that because I got all the way through it and you can kill everybody in that game, and when I got to the end and I went online and there was this nascent forum, a Black Isle Fallout forum. People were talking about the evil ending and I was like, "What? What is this?" I was like, "Okay, what would be more efficient? Would it be more efficient for me to replay the entire game or to take my character into the game and murder everything I come across until I get negative karma?" I'm like, "The latter."

I went in and I killed everything and I got back and I got the evil ending and I'm like, "Wow, that's so cool. The game just lets me just lay waste to all these things." The more I looked at Fallout and I realized that the structure of it allowed me to go straight from Vault 13 to the Necropolis. You can do that. You would never do that on your first playthrough because you don't even know the Necropolis exists, but the game's structure actually allows you to do that and you can get the water chip very quickly.

I started thinking about how that gives a player a huge amount of freedom. They can do stuff in all sorts of weird orders. They can ignore the path and they can do all the stuff and it really made me as a player feel like, "This is not a tabletop game, but it's giving that feeling where the DM says, 'Oh yeah, Vault 15 is over there,' and I'm like, 'You know what? We're going south,' and they're like, 'Uh ... Okay!'" Then they start coming up with like, "Uh, you encounter a group of raiders!" You're like, "Oh my God!"

A good CRPG I think gives you that sense.

When did things start to get a little rough at Black Isle?

JS: Things started getting rough at Black Isle when they were rough at Interplay. Black Isle was a pretty successful division of Interplay, but Interplay had a lot of divisions that were not necessarily successful or a lot of games that didn't really pan out, games that were big budget and that didn't really sell many units at all. Also, Interplay was a publicly traded company, so when things started getting rough for Interplay, they started getting rough for Black Isle.

Granted, it's not like we did everything perfectly. We were developing a roleplaying game called Torn using LithTech. LithTech at that time was not a super robust engine. We were having a lot of technical problems with it and it just so happened that it was at a time when Interplay was starting to get pretty strapped for money and was having not a good time.

Torn was canceled and that was the first time and maybe the only time that Black Isle had layoffs, which was really crazy. We'd never had layoffs before. Then I remember Feargus [Urquhart] and [Chris] Parker and Darren [Monahan] maybe took me into an office and said, "Here's what happening. Tomorrow we're going to cancel Torn, we're going to layoff a handful of people, and we're going to start developing Icewind Dale II." Though Feargus will dispute this, at the time he said, "We need to develop it in four months. What do you think?"

I said, "We can work on that game. It's not getting in four months." They're sort of like, "Well, we're under the gun. Interplay is in a lot of trouble."

The layoffs happened and we started working on it. I worked with Steve Bokkes a little bit and I went home. I said, "I'm going home to write the story." I wrote the story for Icewind Dale II in 48 hours and came back. I wrote the story, I wrote the major characters. I said, "These are all the areas in the game," because I had to come back and this is the first, well, I was the lead designer on a game that got canceled before that, but they said basically everyone just has to go to work.

That was pretty rough. It was very stressful. There was a lot of arguing at that time because we were really under a huge amount of pressure. Later of course, that game slipped to nine months and it eventually shipped in 10 months, which is frankly astonishing that that game. I mean it had a lot of problems but we made the game in 10 months.

It was really rough. I think that was the beginning of Icewind Dale II was the beginning of hard times from my perspective. We had people leaving too because either they were really fed up or stressed out or they just were going, "I don't know if this is going to really pan out in the long run."

A lot of people stayed, honestly, because we still really wanted to make Fallout 3. There was the game that I had been working on that we paused, which was [Baldur's Gate III: The Black Hound]. They were like, "Oh yeah, we're going to stop working on this for now because we need to get a game out in a short amount of time and that one is not going to come out soon." But that game got canceled because Interplay lost the D&D license.

Then Fallout 3 started, but we were losing people and then the founders of Obsidian left. I'm like, "I don't know, we can still maybe make something here," but Interplay was moving in a different direction. At a certain point I realized that we were never going to get this. Like, there is a handful of really talented people working their asses off to make the game they've dreamed about making for years and years and years and we're never going to get to finish it. I was just like, "I've got to go."

That must have been pretty tough.

JS: Yeah. It was really, really disappointing. I can't say that it was completely heartbreaking because I got to make a bunch of cool games and there are a lot of things I would do differently if I had to make them over again and they were made kind of under duress. And also the people I worked with were great, I learned a lot of stuff, and even though we didn't get to make Fallout 3, we got to play through tabletop stuff that was fun. The process itself was enjoyable. I think was more disappointing was to see how Black Isle just collapsed over time.

Some of the things, like the artists especially. There were fantastic designers. Don't get me wrong, amazing designers. The artists at that studio, Justin Sweet, Vance Kovacs, Jason Manley, Chris Applehans, Andrew Jones, Kevin Llewellyn. Just phenomenal 2D artists. John Dickenson. I can't even name them all. I took for granted, "Oh, like wow, I guess the game industry is full of phenomenal artists." I mean it is, but Black Isle really had this incredible stockpile of fantastic artists.

Anyhow, it was just sad because it was a studio that, when I got there, was just people worked really hard because they wanted to work hard, not just because they were under, well, they were under pressure too. Don't get me wrong. Especially the Torment team was under a lot of pressure so I don't want to misrepresent that. People were working hard in part because they just wanted to make something awesome. It was just like at every step of the way is getting huge bags of concrete put on your back.

What was the moment you decided to leave? Was it you just kind of looked around and said, "I don't have enough people to make this game?"

JS: The moment I decided to leave was literally, we had a great character artist on our team, and he was like the only character artist left on the team. Interplay senior development pulled him over to a non-Black Isle project. I'm like, "Okay, you know what? If you're going to take the only senior character artist off of this project, you have no interest."

The other thing too is that Tom French and I... Tom had taken over as producer on the project. We had been sort of begging Interplay development, like the upper management, to come over and look at what we were doing. We were like, "Dudes, we're making something really cool. We're super excited about it. You got to come see it. We're scheduling stuff. You can take a look at our budget, our schedules, all this stuff." We were working hard to make something amazing and they never came over and looked at anything. It was really disheartening. It basically made me think, "They have either no interest in what we're doing."

Black Isle really seems pretty special to you in hindsight.

JS: I don't want to overstate it because there were certainly problems there. I don't think I would want to work in that environment now, to be honest. I mean it was an environment of, again, dudes, many of whom had a lot of personality problems, who worked too hard and so had a very myopic view of things. I'm including myself in all of this. By the same token, it was the first job I had in the industry. A lot of people come into the game industry at companies that are not making anything particularly noteworthy, to be honest, and I just completely lucked out.

Like if you had asked me before anything, "What company do you want to work for in the game industry," I'd be like, "Black Isle. I guess they're the guys who made Fallout, right? Okay, I want to work for them." Maybe Ensemble at the time because I was really into Age of Empires.

It's funny because as Black Isle was imploding, I did interview at Ensemble. I went over there and I do remember one design. It was great because I got to meet Sandy Petersen. He was a person I did remember because he worked on Darklands, which is one of my favorite games of all time. At the end of it, I met everyone, it was a really good time and they said, "You should keep working on roleplaying games."

Is there a single project looking back on Black Isle that you're like, "Yeah, that was my favorite," or maybe most proud to be associated with?

JS: I guess I would say, there's something that's kind of, have you seen Jodorowsky's Dune? That documentary about, I think it's Alejandro Jodorowsky. He was making a version of Dune before David Lynch and it was insane. It was absolutely ludicrous and he pulled together all these people who later went on to do Alien and all this other stuff after the movie imploded. It was canceled right as they had all these amazing ideas together that were just phenomenal. He said, "It's the perfect movie because it never had to come out."

The Black Hound was the game that I always wanted to make. It's like everything that I like about D&D, it's everything I like about the Forgotten Realms, with none of the stuff I don't like about Forgotten Realms and the way I want to tell a story and the way I want to do this. It was this huge game: 1,600 pages of design documentation for it. I was a lunatic, like, "Yeah, it's gonna be this big! It's three times the size of Baldur's Gate II!" I mean it wasn't quite that big. but it was enormous. and it had all these companions and all this other stuff.

I feel like with The Black Hound and with Fallout 3, we didn't actually get to achieve that stuff. We got to start doing it and then go like, "Hmm, maybe this would go wrong." Then later on like when we worked on Fallout: New Vegas, we got to say, "Okay, what are some things from Van Buren that we think actually could be cool on this engine in this setting?" Then on Pillars of Eternity it was like, "Okay, what are some ideas from The Black Hound that I think would be cool coming over into this?"

I think about The Black Hound as the thing that I'm happiest with because it never had to suffer reality. But of games that actually came out, I'd say Icewind Dale. I think it's kind of astonishing again in some ways that it was really just a bunch of juniors just making stuff and we didn't really know what we were doing. We just were like, "Let's put a bunch of stuff in and make areas," and it came out actually reasonably well.

Interlude at Midway

After the collapse of Black Isle, Sawyer moved on to Midway, where he spent the next year and a half.

You weren't at Midway very long. Were you just seeing it as a transition point? What was it like there?

JS: It was interesting. I came over to work on Gauntlet and Midway was sort of trying to refocus itself as a leader in mature titles because of Mortal Kombat. They wanted to do it with Gauntlet. I'm like, "Okay, mature, like M-rated Gauntlet? Holy crap, what does that look like?" I just kind of went wild on it.

I came over, and John Romero was there as the lead designer, and then he later took over as creative director and made me the lead designer. I hadn't worked on console games before, so that was new, so I had to learn a lot about that. Thankfully there were some really cool folks there like Mike Cuevas who had worked on Ready 2 Rumble, and he taught me a lot about how to work on console games and action games and things like that.

I had gone from one sinking ship to another sinking ship because Midway was not in a good position. It just came down to the point where I was really cognizant of not staying at some place when it was really hopeless. Because I should have recognized Interplay was not going to support Black Isle much earlier. At Midway, I was much more cognizant of, "There is a big company here that doesn't really care about me and it doesn't care about you as much as you care about games."

Now granted, again, the development team, it's not like we did things perfectly. We made a lot of mistakes. I can't remember even how much money we spent on an intro cinematic that was like super M-rated. Crazy stuff. They were like, "Hey, we notice a lot of kids play this game, it's kind of a family game. We should make this T." I'm like, "Holy crap, dude, the whole game is designed around being M! You've got people chopping heads off and doing all this crazy stuff," and they were like, "Nope, it's going to be a Teen rated game."

They also wanted to death march everyone for six months. They said, "Okay, we understand that was going to be this much time but we really need to get the game done and so we really need you guys to do this, and Midway rewards teams that deliver so just stick with it." I'm like, "Nope! Nope! I'm out, I'm not going to do it." Because I knew that no matter what, no matter how hard we worked, this game was going to be half-baked. I was like, "I did not come here to just make something that is shovelware," because it was being made just to get out, and so I left and a lot of people actually were really mad at me for doing that. I said, "I really do not think this is going to go well."

At the time, Darren Monahan had been talking to me about coming to Obsidian because they were in the middle of Neverwinter Nights 2.

I was going to ask, were you recruited?

JS: It wasn't like I stopped talking to everyone here when I went down to Midway. I would talk to Darren on MSN Messenger or whatever and he was like, "Buddy, come up here!" I'm like, "I got a game I'm working on!" Then, yeah, I said, "Hey dude, I think I'm going to hit you up for that." In the end that Midway team got that game out for Christmas and then they were laid off and the studio was shut down. I shouldn't say they were all laid off. Some of them were given the option of going off to LA, but it didn't really work out.

I learned a lot from those folks. I do feel kind of bad that I wasn't able to help them, but I would have been helping them just get something out that I don't think was that great. Not for the fault of anyone working on it. After Midway, I came up here and started working on Neverwinter 2.

Obsidian: The Next Chapter

JS: Yeah, relatively new. It was 2005, so it was almost two years into their development. They had already shipped Knights of the Old Republic II and they were working on Neverwinter Nights 2. They were at full speed on Neverwinter Nights 2. I was really burned out from Midway, really disappointed, and I said, "You know what? Can I just be a senior designer? I don't want to be a lead, I don't want to be in charge of anything. I want to be in charge of some areas. Just let me go back to designing areas and working on systems and I'll be totally fine," and they were cool with that. That's what I started doing.

You must have felt like, "I'm a hardened veteran at this point."

JS: It's not so much of a hardened veteran as much as like I saw a bunch of really young, very ambitious people and I was like, "Okay, everyone's kind of just doing stuff." I mean six years is really not that much time, but it was enough that it didn't feel like it was very organized. That was my first impression, where I was like, "There's a lot of cool stuff going on, I don't know what everything going into this game is," but I'm like, "Okay, this is my chunk of it and I'm going to try to just take charge of it and make sure that this is really solid and good."

The thing with Neverwinter Nights is it had a lot of bugs when it came out and that kind of thing. I think that happened a fair amount at Obsidian. It was kind of a case of ambition meets limited resources?

JS: Very much so. I'm not always responsible about resources, but I'm fairly responsible. One of my main concerns coming onto Neverwinter 2 was, "I don't think all this stuff is going to get done. I don't think all these areas are going to get done, I don't think these quests are going to get done, I don't these prestige classes or these abilities are going to get done. I think we've got to start getting real serious about cutting this stuff."

I will say, I had set a really bad example at Black Isle.

Because you liked to write 1,600 page design documents?

JS: [laughs] I mean seriously, that's what I had designed. I guess the thing is the rubber never really had to meet the road on that because I was in documentation land for a really long time. Then I looked back at it and I was like, "Oh, that was a bad way to do that. Of course we shouldn't have done that." Midway was much more production oriented and so I started going like, "Oh crap, I really have to think more carefully about this."

Again, it wasn't like I was innocent in all this stuff but I was very concerned when I came over. One of the main things that I had said to the owners at the time after I did a more long term analysis of Neverwinter 2 is, "Hey, KOTOR 2 came out and it was really buggy and a lot of people were mad but they were like, 'Okay, this was their first game.'" I said, "Neverwinter 2 can only be so buggy or else we're going to become the studio that makes buggy games," which is exactly what happened. That was really my concern, which was, "Hey, if you want to make the number of bugs go down, don't put as much stuff in the game and be more responsible about how you put it in the game." It really took a long time for the project to get to the point where that was the reality check.

I actually moved off of the project for several months because I was concerned and I didn't really feel like, "I don't know, I don't feel like I'm able to contribute to this team because I have these concerns that don't really seem to be shared. There's a console game or some, you know, pitches and things that are going on. Maybe it would be better if I contributed to those because I don't want to be the guy who's just saying, 'Hey everybody, listen to me! There's trouble!'"

I went over and I worked on another project for a while and then they brought me back over to Neverwinter 2 to just clean it up and get it in order. Because it was rough. It was rough for a very long time.

It was maybe around this time that publishers moved away from isometric RPGs. I know that you've told me in the past that this was kind of frustrating on you. In that moment, what was that like?

JS: It was kind of annoying. To be honest, that whole intermediary phase was a little frustrating because I remember when we were working on Van Buren, it was a 3D game but it still had... I wouldn't say isometric, but it was narrow field of view, top down camera or three-quarter view camera. I remember some people saying, "Why is it even 3D if you're not going to get in close?" I'm like, "What do you mean? There's a bunch of cool stuff that we're doing with the 3D. We don't have to be first person or close third person. Plus if we want to have a party, we want to do all these things.

On Neverwinter 1, BioWare made certain choices. This is about design and choices and accepting the consequences. BioWare made playing Neverwinter about your character. Like you make a character and you control that character and you have companions but they're more satellites. They're not controlled like they are in Baldur's Gate. The camera is fairly close to you, you're fairly close to the action. It's a very different feeling from Baldur's Gate or Icewind Dale or Fallout.

In Neverwinter 2, we had three camera modes and none of them felt that good. There was a tradition iso camera, there was a follow camera, there was one other one that I can't remember, which goes to show how important it was. It was this weird thing where we were like, "Well, you have a party but we want to also support this 3D follow cam, but you don't really want to fight in that mode because you can't see your party." It was a struggle to try to get into that space and figure out how we want to set up cameras.

The camera is the way that you view the whole game and so the decisions that you make with that are ultimately going to have a big effect on can you have party members, how do you control party members? Even thinking about something like Mass Effect when BioWare started going into close third-person, and I'm thinking about you have other characters around you, how you command them and understand where they are relative to you is a tricky thing to solve.I was disappointed to no longer have the sort of high top-down camera to play with, but more than that, it was frustrating trying to find a middle ground. We didn't really do a good job of finding a place where it's like, "Ah, this feels like the game that you know and love but it looks fresh and modern." Those were things that weren't really that compatible.

The Canceled Games

If the 2000s taught you anything, I'm guessing it's that AAA is a brutal business. Is that fair?

JS: I don't know. I guess it depends on what you define as AAA. I do think that dealing with publishers is really hard. One of the most difficult things that I think Obsidian had to deal with that Black Isle did not have to deal with, Brian Fargo understands what roleplaying games are about. He gets what roleplaying games are about. Keep in mind that my first CRPG was Bard's Tale, so coming to Interplay and meeting Brian Fargo, although I doubt he remembers initially meeting me, I was like, "Oh my God, this is incredible!"

Brian played games at Interplay. He would get mad. He would play multiplayer games and get upset. The "by gamers for gamers" thing, with Brian, I believed in that. I was like, "This dude, he gets games, and he gets roleplaying games.

Most publishers have a blind spot when it comes to roleplaying games. Roleplaying games are very esoteric and they have very specific needs and the audience is very specific about what they want and don't want. Publishers, when they talk to us, it's like they don't really understand where we're coming from and so a lot of times when we say like, "Hey, this is important," they don't understand why or they don't believe it is." They're like, "No, no, no, this thing is more important because the mainstream audience." We're like, "Okay, but hold on. This game fundamentally is not one that really is mainstream, so when you do this, the mainstream people, they're going to play it. Then the hardcore fans that really love it are going to hate this."

The 2000s were like the period of that. It was all this kind of like, "Oh come on, do we really have to do this? Is anyone actually going to enjoy this?" There was a lot of fighting over that. That's one of the reasons why on Pillars of Eternity it was like, "Woo!" Because we're just talking to fans, reading the boards, seeing what they say, getting their feedback and trying to respond to that.

The 2000s, it wasn't so much that AAA is brutal. It's just that publishers don't understand roleplaying games. At the beginning of my career I didn't have to deal with that because everyone at Black Isle understood roleplaying games and Brian Fargo understood roleplaying games. Who else needs to understand anything? Then it became more difficult.

The Aliens RPG was famously canceled. Can you open up about that at all?

JS: Cool. I thought it was going to be super cool. I want to say that it was Travis Stout who... he was a designer here for several years. He, I think, wrote up the initial pitch for it. So one of the things that I was most interested in exploring was the spacefarers who are now the engineers in the rebooted Aliens universe. That's what I wanted to explore and focus on. In terms of mechanical stuff, it was really focusing on a large group of companion characters who are working together to try to survive.

In my mind, the Alien setting is fantastic for a roleplaying game because I think about characters and character interactions. Especially the first two films, I think you can argue that all the films are about these relationships but Alien and Aliens at their core are about these human relationships and how people respond to stress and break down and help each other or turn on each other and all these things. That's what I think makes for great drama in a roleplaying game.

I liked the idea of coming into some environment where really it's not about, "Oh, I'm going to meet a world full of NPCs to talk to." I think that's what a lot of people think about when they think about roleplaying games, is like there's a big world and there's 200 NPCs and they all have dialogue. The way I thought about an Alien roleplaying game was that it's you and a small group of survivors and that is it, and it's about your relationships developing as you're like, "How do we survive? How do we get out of here? Who's on my side, who's turning against me," and all the dynamics of that.

People saw the leaked footage where it was about primarily, like a third-person, and obviously it was really rough but it was like a third-person exploration shooting mechanic. You had two companions with you at any given time and a handler. The handler would help sort of manage what was going on and call out things for you and your two support people would do various tasks like cutting through doors or setting up turrets or things like that or hacking. That was really the whole vibe of the game.

You weren't thinking in terms of, "How can I make really scary aliens?" You were thinking in terms of the scene from Aliens where Hudson is going, "Game over, man! Game over!"

JS: Yeah. Don't get me wrong. That was also very important and we did put a lot of work into lighting and sound and all that sort of stuff. I think in the leaked footage you can see where we have those little stingers or things moving and sounds playing. We did try to convey the horror sense. That was always the mood that we wanted to convey. But in terms of the mechanics we wanted to bring across, we wanted to think about the human interactions and how you manage this group of people and how they try to work with you or against you over however many hours it would take you to get through.

Was the atmosphere and the character interactions the thing that you were most proud of on that project?

JS: Yeah, I think so. What I really love about Alien is that it's a very small cast and you get to know those characters at a deeper level and you see them each break down over time. It's also really great because it's this kind of like blue collar space horror movie.

What I liked about Aliens, and this is something I think James Cameron does very well, which I'm just going to say I don't think Ridley Scott actually does very well: James Cameron does a good job of introducing a lot of characters in a brief amount of time and establishing strong characteristics that you remember about those characters. In Aliens, when you meet Vasquez, Frost, Hicks, Hudson, these people, some of them don't have a whole lot of screen time but you get enough to know something about them and to have a connection with them.

I liked the diversity of all these different characters. You got military people, you got company people, and you got blue collar workers. That's kind of the idea for the classes. We're sort of forming, like these are the sort of people that you're with. I was really most interested in establishing a range of these people from all over the world: different ages, backgrounds, really diverse appearances, because I think that's really important, because we weren't doing anything fantastic. We were doing something that's more grounded sci fi like Alien and Aliens, which was to try to bring out a lot of character just from using things that didn't look like costumes. They were like, "These are the clothes that this person wears." We put a lot of work into that and I think it was coming along really well.

Cool. You would have been stuck on a planet, the aliens are coming, kind of like Aliens, right? Just like, "How do we get out of here?"

JS: Yeah, and figuring out what the heck was actually going on on this planet and focusing mostly on the spacefarers, the engineers and what their deal was.

What would you say, I mean Obsidian obviously has tons of war stories. What would you consider a shining moment for you in your time here?

JS: Getting New Vegas done. That was a huge challenge. It was an opportunity to work on Fallout again, which I never imagined that I would get that opportunity. A lot of people had wanted to work on Fallout. We had no experience working with that engine. The first person who came here who had experience working on the engine was Jorge Salgado, who was a modder who had made Obscuro, an Oblivion overhaul, while the rest of us were completely clueless.

We just went wild and it released kind of bumpy. There are things that we certainly could have done better on it, things that I could have done a lot better on it, but yeah. We got that game done in 18 months and it's the game that, if someone were to just say, "Hey, what game of yours should I play," I would say Fallout: New Vegas. I think it's the easiest to get into, it has a ton of reactivity and player options. You can make a huge number of different characters. I'm happiest with that, especially considering the amount of time that we made it in.

What's kind of a defining war story for you here at Obsidian, a moment when the rubber hit the road?

JS: The end of Neverwinter Nights 2, I guess. I would say that even on Fallout: New Vegas, we had a little bit of mandatory overtime on that, but it was actually not too bad. We were stressed on that. Neverwinter Nights 2, I mean I was like the butcher of Neverwinter. I came in and I was like, "Get rid of this, get rid of that, cut these classes, we're not doing this feature, get rid of all this stuff." It was really rough. It was also really rough, there were a lot of people here who were busting ass to make that game be awesome, but it was enormous and there were so many things left to do.

At the time I was living in downtown San Diego or like Hillcrest, and I was taking the train up and down every night and it was an hour and 50 minutes each way. I would get up at 6ish or whatever and I would get home at sometimes 11:30 or midnight. I would take the last train back. That was not easy.

It was all just... it was really just triage. It was me being like, "How many quests do we have in this area? How far along are they? Okay, these three are barely started? Cut them. Just get rid of them. Figure out how to clean up the loose ends and get rid of them." Because we were already way behind schedule and over-budget. That was really rough. We got through it but it was stressful.

What about Stormlands?

JS: Yeah, I was the director on Stormlands. The end of that was very, very sad because we had to lay off a ton of people. I think on that project, with Neverwinter Nights 2 we were death marching to get that out. With Stormlands, it didn't end in quite the same way, but it was a more catastrophic ending because of the layoffs and everything.

My understanding is that it became Tyranny at a later point.

JS: I wouldn't really say that, no. There were ideas of, I think there was actually a name for Tyranny. Maybe it was Defiance or something like and then there was the TV show and the game called Defiance and we changed it. There was a period in time where we talked about using that tech in that way, but none of the story elements, none of the characters, none of the mechanics really were coming over. It was like, "Hey, we have this technology that's actually pretty cool. Do we want to use it to make a different game?" Then Avallone had ideas for Defiance, which later became Tyranny.

You had the tech from Defiance.

JS: We had the tech from Stormlands and we talked about, "Hey, we maybe make a different game. We could make a different game in this technology which is very beautiful, it works great on consoles and all this other stuff." Then we did Pillars and we said, "Okay, wait. We don't want to probably have two completely separate code bases. Do we really have the staff to make this huge third-person console-oriented game, or should we make Tyranny using essentially the Pillars of Eternity technology?" That's how that kind of went.

There's nothing really in Tyranny that's from Stormlands. The only link there is that after Stormlands was canceled, we were like, "Okay, we've got this engine. Do we want to make something with this?" Then we said, "Actually no, we don't. We want to make something with the Pillars of Eternity technology."

What was your vision for Stormwinds?

JS: Oh, I wanted to make a weird, wild fantasy thing. It's just a bizarre, a fantastic and beautiful land of crazy stuff and really pushing the artists to make imaginative and beautiful things. A lot of the ideas for it were actually inspired by Justin Cherry, and his art which is very fantastic.

I think one element that is similar between an idea for Stormlands and Tyranny is the idea of a sort of post-apocalyptic magical setting. I was like, "We're going wild, we're going to have crazy architecture of bizarre materials and it's just going to look brilliant and colorful and fantastic and just really, really unique." There were struggles with it because any time you really try to synthesize something that's really fresh, that's a hard thing to conceive together, but it was fun. It was really fun working on that.

Pillars of Eternity, it's often been said that it's kind of a studio saving success. Is that fair?

JS: Yes. I would say so. Don't get me wrong, it's possible we could have done something else that also kept the studio afloat but Pillars definitely, not only did Pillars financially work out very well for Obsidian but it reversed the morale at the company which was at its lowest following Stormlands cancellation, like bad, bad, bad.

Yes, that story's certainly been written. Now you're making Pillars of Eternity II: Deadfire. You've successfully crowdfunded multiple projects. Is there any chance that you might return to AAA at some point in the future?

JS: I think Obsidian would like to. I think Feargus would certainly like to make AAA games. I, frankly, could take it or leave it. If I never made a AAA game again I would be totally fine with that. I feel like I got to do that on Fallout: New Vegas and that was really cool, to make a game that literally millions and millions of people played and the surreal experience of... I remember coming home and my girlfriend at the time was watching South Park. A commercial came on and there I am on TV. Like, "What the hell is this?"

Bethesda had taken these interview clips and they had bought ad time for Fallout: New Vegas during South Park. People from high school contacted me on Facebook and being like, "Dude, did I just see you on South Park on Comedy Central?" That was surreal and cool. It was cool to be driving down the 405 in Los Angeles and see a billboard for Fallout: New Vegas. I was like, "What in the world is happening?"

That's cool. I don't feel like I need to do that again. I feel like I made a cool game that was a big game, that tons of people knew about and had a huge advertising budget and all this crazy stuff. That was, neat and if I never do it again, that's okay. Because that game is the game that I'm most happy with. I was totally happy making Icewind Dale, I'm totally happy making Pillars of Eternity and Deadfire. If I made something smaller than that, I would also be happy doing that. Personally I don't need to work on huge games again. If I got an opportunity to and it were the right game, then yeah.

I do know that, one of the things with Stormlands that in a way was cool was that Microsoft was totally actually on board with every insane world-building thing that we wanted to do. It didn't matter how ludicrous or crazy or wild, they were like, "Sure, awesome, sounds great!" I'm like, "Wow!" I know that AAA development is usually much, much more conservative than that. There's a trade-off there. Once you start designing for a truly mass market mainstream audience, you have to be really conservative and mainstream with your mechanics, with your characters, with your stories, your dialogue. Or maybe you don't have to but it's a very delicate balance.

I enjoy making hardcore stuff. I like making games like Pillars and Deadfire that are much more numbers oriented, they require a lot more tactical thinking, they require you to read a lot more than I think most AAA games do, and I'm totally comfortable with that.

How have the past 18 years changed your perspective on RPGs?

JS: That's an open question. I don't know. I don't think that they've really fundamentally changed tremendously. I think that I still found that the greatest value in RPGs came from finding ways to let players be part of the story. There's lots of different ways that you can do that, but even coming into the industry I still had that feeling that, yeah, this is about us making a space in which players get to define their own story, which on Icewind Dale was a little weird. I felt a little uncomfortable because it was so linear. It was a fun game but it was fundamentally a dungeon crawler and I was like, "I want to build something with more space than this."

I think when I came into the industry I viewed RPGs as a thing that needed to be designed a specific way, like there was a way. I think this is a common thing, like a game designer early on, they have ideas and then as they start to work they think, "Oh no, okay, this is the way that you design a game." I think now I'm in the phase where I feel like the challenges of designing an RPG are the challenges of designing anything, not just in a game, anything. A chair, a car. Anything at all.

The most high level design principles where you're thinking about, "What are the needs of what I'm doing? What are the constraints of what I'm doing? Who is this for?" Starting to abstract those things and think more like, because you can design a game like Fallout: New Vegas that's... it's not hardcore in terms of its mechanics at all, it's actually a pretty simple game in most ways, and still say, "This game, this is a mass market game. This is a game for millions of people to play, and so I'm not going to go crazy on these mechanics." I mean I went as crazy as I could but then I stopped short which is why I made the JSawyer mod. It's like, "Actually, let me get more noodly with this stuff."

It's a pretty easy game. It's not that challenging in a lot of ways, but it's about, "Okay, this audience wants the feeling of exploration. They want the cool story." I feel like the place where the tabletop stuff comes in that the mainstream audience can also benefit from is the freedom of choice. You can ally with whomever you want, you can go your own way, you can ally with Mr. House and then betray him, you can do all these things. That doesn't require a hardcore audience, it doesn't require a mainstream audience. It's just a thing that I think people will think is fun.

Something like Pillars, there's a lot that goes into it where I'm like designing a class. I like classless systems more than class-based systems, but the audience for Pillars of Eternity wants a class based game. Rather than say, "Well, I'm going to turn this upside down, you ain't never seen classes like this," that's ridiculous. No, make a good class-based game where people can have a lot of options, they can make cool characters. Things like make sure there's plate mail, make sure there's flairs, things like that where it's about feeling.

I think in RPGs you can get lost in the technical aspects of the systems and things like that, but really even those systems are about giving the players a feeling at various points. Like, "How do I feel about the game? What is this making me experience emotionally?" That can come from mechanical things, it can come from story things. I think over time, I've stopped really thinking that there is a single way to really design anything. It's about, "Well, what are the trade-offs?" Who are you going to design this for? Who are you not going to design this for? If you want to do this, can you accept this drawback or can you design it more like a little bit over this way and then this problem goes away? Is that acceptable or have you lost the essence of what you were going for?

I've just started to view RPGs as something that's, it's like any other design problem. It has a lot of unique things to it, but fundamentally it's like any other game or any other thing that you have to design.

One last question. Obviously you've gone through many tough times but also many amazing times. Is it a relief to find maybe a modicum of stability here at Obsidian after so many years? Also, what's the future hold?

JS: No, I don't think anyone likes living in an unstable circumstance. I mean growing up, my dad was a sculptor. He's a freelance bronze sculptor which is not exactly a super stable sort of thing. That could be rough at times. That's why we moved around a lot. I don't think anyone likes the fact that the industry overall is unstable. It still is not a very stable sort of place. The fact that Obsidian is coming up on its 15th year, most companies don't last that long.

Especially not a studio like Obsidian, a mid-range independent studio.

JS: Yeah, we're very uncommon. It is very nice to be in this position but we have to keep working. We have to keep building our IPs. The thing is too, again, 18 years has also given me the perspective of... I remember going to Ensemble to interview around the time of Age of Empires III being like, "Oh my God, this studio is amazing! This is incredible! I can't believe all the people here and all these facilities are incredible," and then within four or five years, they're gone. I know that you just can't take any of this stuff for granted. It's certainly nice to have some sense of stability, but I think anyone who's been in the industry for a while knows it's never really that stable.

As far as the future goes, I really want the next game I work on to be a historical game. It's probably going to be even smaller than Pillars or Deadfire. As far as Obsidian overall, that's for the owners to decide. I work on the projects that I get the opportunity to work on.

Josh Sawyer's next game is Pillars of Eternity II: Deadfire. It's due in 2018.