Guided by Voices

Eurogamer's Jeffrey Matulef catches up with Davey Wreden behind the scenes of his mental meta madhouse The Stanley Parable.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The Stanley Parable creator Davey Wreden is a PR person's nightmare.

"In a way, the whole point of The Stanley Parable was to create something that was intrinsically difficult to describe," he tells me, upon revealing the completely bonkers PAX demo he created specifically for the occasion. The whole "you just have to play it" mantra is too vague to function as a selling point, and God help the poor soul who's tasked with writing a press release for this highly experimental satirical curio that not so much breaks the fourth wall as completely demolishes it and digs a chasm in its place just for good measure.

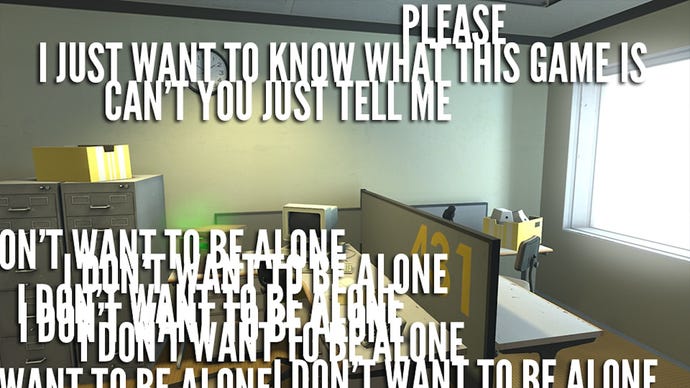

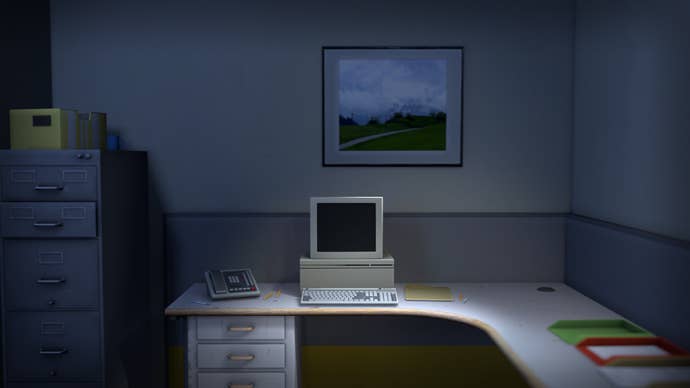

So what is The Stanley Parable, you ask? At its core, it began as a Half-Life 2 mod in which the player assumes the role of an office worker named Stanley who's having a rather unusual day. A delightful British narrator explains Stanley's peculiar set of circumstances just before the player is asked to enact them. When facing two doors, the narrator will explain that Stanley took the left one to the cafeteria, when in reality the player can subvert the narration by taking the door on the right, at which point the narrator will comment on Stanley being terrible at following directions. Saying any more would ruin astoundingly labyrinthine onion-like layers of narrative tangents the player can embark on in what feels like the unholy interactive offspring of Inception, Being John Malkovich and Portal.

It's hard to say more without dryly ruining the jokes as much of the fun comes from the narrator constantly reacting to your input in increasingly unpredictable ways. Most games put the player in the role of a listener, sitting cross-legged on the rug while the developer spins them a yarn, while other titles are more akin to Choose Your Own Adventure books with plenty of branching narrative paths that are usually tied to moral or strategic choices. The Stanley Parable, however, is more like playing improv theater with a robot comedian who was programmed to be much, much funnier than you. Only the Stanley Parable's puppeteer isn't a robot, and like the funniest comedians, his humour comes from a dark place.

In Wreden's case, The Stanley Parable, his first game, emanated from feelings of alienation. There's nothing outwardly off-putting about Wreden -- a handsome lanky young man from Austin sporting a rainbow-colored mohawk -- but he felt like he couldn't connect with other people in a meaningful way. "I'm fascinated by conversation," he tells me. "I'm fascinated by the language that people use to describe things to one another that don't have very convenient words for. Feelings like a passion that you feel or a person, or a thing, or a sensation. Describing an experience that was like a very personal experience that you went through. Maybe you went to a country somewhere and maybe there was a night where the most incredible thing happened and you felt so alive and you come back and you want to talk to other people about that one thing that you went through because that was so meaningful. And you know that no one else would ever have gone through that, right? So how can you put it in words? How can you describe it in such a way for someone else to know?"

"When people are at a total communicative impasse I'm always freaked out by that idea," he explains. "I'm always thinking 'there must be a way to get you to understand what the other is thinking. It must be in the language. It's something about the language that we're using that isn't precise enough. That isn't fine enough. Or doesn't convey intricately enough what you're thinking or feeling.'"

I suggest that perhaps the problem is that he's chronically indecisive. Writing, as it turns out, is hard. That stereotype of the scribe overflowing their waste bin with crumpled up wads of paper is unusually apt (or was before word processors, anyway), but the really hard part about writing comes when you have a few drafts left and you like all of them. Only one makes it to the press, so which one version do you wish to go with? Wreden sidesteps this in The Stanley Parable by making its malleable storyline and reactive, neurotic narrator an expression of his scatterbrained thought process.

"In a way it's autobiographical," he tells me. "What it starts with for me is sort of a history of emotional anxiety, of feeling sort of uncomfortable in my own skin about how I present myself to other people. The original Stanley Parable starts with Stanley being alone, right? He doesn't know where everyone else is. I think that's how I felt at the time. I didn't know where are all the other people that I feel comfortable around? Where are the people where I feel like I can just be me around? I wasn't really thinking about that at the time, but when I look back it's actually pretty clear that that's what I was trying to say: that I don't feel comfortable around people a lot of the time."

"I'm sure that anyone who's played the game will understand that I was that guy," he adds. "About the time when I was creating the original game I went through a hardcore depression on this nonstop [track of] thinking about the fact that I was thinking about the fact that I was thinking about the fact... forever. It was awful. It was the kind of thing where you're thinking 'Am I going to be this way forever? Am I always going to feel this way about the world?' And part of the original Stanley Parable came out of this uncertainty."

While Wreden never set out to make a semi-autobiographical game about grappling with mental issues, his over-analytic perspective shaped The Stanley Parable into the maddening masterpiece that it's hailed as in some circles. "Strange, marginal, out there thoughts are a super normal part of your experience all the time," he says. "Usually we like to pretend that we're these rational thinkers. That we're normal. I think feeling confused and schizophrenic about your thought patterns are totally normal and everybody feels that. We're always doing that all the time and I'd just like to call attention to it."

Thankfully for Wreden, people did connect with his plucky, silent first-person avatar and the sometimes brilliant, sometimes foolhardy voice in his head. "When The Stanley Parable came out, people started talking to me about it, and I realised that a lot of people got what I was trying to say," Wreden smiled. "I've been able to meet people and they already understand me in some way. That was not really my intention going into it, but it somehow very serendipitously ended up happening that way and I realised in retrospect that maybe it was more autobiographical than I thought it was."

Connecting to other people this way has been Wreden's primary driving force in continuing his new career as a game developer. "I could very easily start doubting that anyone would ever actually want to play a game like this, but people seem to be really enjoying it, so I guess people want to engage with that. As long as I feel that it's actually making an impact and it is actually giving someone a positive reference point to think about themselves and the world, then I feel like I want to keep doing it," he explains.

But now that Wreden's disposition has grown sunnier, how will the affect his unique brand of humor? "I think my sensibility has just been getting more comedic as I've just been feeling happier and happier," he says. "I feel like over the past couple of years I've just become a happier person and that's reflected in my work."

This is certainly apparent in the PAX demo, a standalone slice of comically convoluted mayhem that captures the spirit of the game without actually letting you see any of it.

This tailor-made teaser begins with the player taking a number from a waiting room and eventually the narrator comes into play and tells you he's going to introduce you to The Stanley Parable's demo. After requesting you to stand still for 15 minutes to relish this anticipation, he eventually gives in when the player naturally decides not to comply. Upon much pomp and fanfare, you slip past the tantalising proverbial curtain to finally try the demo, only to emerge right back in the same waiting room, this time with the narrator already in tow, perplexed by this sense of deja vu.

This time the narrator apologizes for the error, but is confident that as soon as a mammoth gate full of TV screens opens, you'll be able to finally enjoy the much anticipated demo for The Stanley Parable. The colossal door slides open to a blinding white light and the player is finally treated to... Octodad 2: Dadliest Catch! Well, sort of. It's actually a room full of Octodad 2 paraphernalia, but the room is clearly meant to commemorate Young Horses' physics-based comedy. "If you like Octodad so much why don't you go around the corner and play it?" The narrator digs, seemingly aware of the fact that Octodad 2 really is a few meters away in the Indie Megabooth. Well played, Stanley narrator. Well played.

Amazingly, Wreden isn't done surprising prospective players with offbeat marketing ploys as the new trailer for the remake contains yet another unpredictable riff of the premise, this time initially replacing the narrator with a real Let's Player who gradually morphs from prospective player to part of the story.

Even with the glut of first-person non-shooters like Dear Esther, Thirty Flights of Loving, and Gone Home exploring as wildly divergent storytelling techniques and atmospheres ranging from serene loneliness to zany capers and nostalgic romance, there's still nothing out there that feels quite like The Stanley Parable. Of course, I haven't actually played its remake yet, but if Wreden's self-made marketing manoeuvres are anything to go by, it doesn't seem like our boy Stanley or the parable that encapsulates him has run out of Steam yet. Forget video games' search for its Citizen Kane; I think we just just found the medium's Charlie Kaufman.