Gaming's Greatest Flops: Shenmue

Was Yu Suzuki's magnum opus a hubristic failure, or an evolutionary path left untraveled? As its 15th anniversary draws near, we find the answer could be somewhere in the middle.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Every Thursday this August, Gaming's Greatest Flops will examine one of our industry's biggest failures in an attempt to understand what went wrong. This week: Sega's great white hope for the Dreamcast, Shenmue (1999).

The 2000s opened on a sour note, with the catastrophic failure and subsequent exile of two video game visionaries. Square's Hironobu Sakaguchi bet the farm on Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, and this attempt to bring his series to a wider audience ended with box office returns that didn't come close to recouping the film's $147 million budget. Artists floundering in a new field provide the most common stories of failure in the entertainment industry, though, making the tragic tale of Yu Suzuki's Shenmue all the more devastating.

Shenmue is widely known as the game that killed Sega, but obviously, their financial state offered little hope for fans before the time of its release. But true believers knew in their hearts this game would be the one to save the industry's scrappy underdog. After all, Shenmue would be helmed by none other than Yu Suzuki, the man who rose through the ranks at Sega by developing games like Hang-On, Space Harrier, Out Run, and Virtua Fighter: spectacle-based arcade experiences offering minutes of jaw-dropping visuals for only a quarter. This new creation, which began life as an RPG, would be unlike anything else he worked on—an experience so new it required the christening of an genre. We didn't quite know what "FREE" (Full Reactive Eyes Entertainment) entailed, but that didn't mean we weren't anxious to find out.

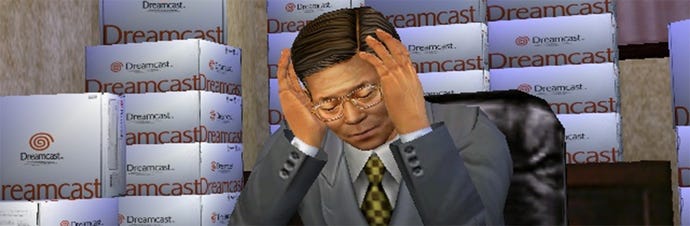

It's important to note that Shenmue entered development before the concept of the "open-world" game had been fully realized, mostly because console hardware of the era could never support such a technologically ambitious experience. In fact, Suzuki first envisioned Shenmue as a Saturn game, though the console's general failure and unfriendly hardware caused his team (which numbered over 300) to instead focus their efforts on the Dreamcast after six months of development. Due to the complexity of the game, Shenmue saw its share of delays, and a demo disc sent to those who pre-ordered it in Japan—titled What's Shenmue?—contains some self-effacing humor that points directly to Sega's troubles at the time. The preview disc co-stars Hidekazu Yukawa, Sega's Head Managing Director at the time, and when protagonist Ryo stumbles into the man's office, he's depicted cradling his head in his hands, surrounded by boxes of unsold Dreamcasts. Even if Sega had a sense of humor about their plight, they clearly understood something was about to give.

In our modern era, we scoff at the presumption of video game publishers who announce entire trilogies before anyone can even react to the first installment. Back in 1999, Yu Suzuki envisioned Shenmue spanning 11 chapters—a somewhat arrogant plan, especially in the years before digital distribution. In all fairness to Suzuki, he at least had the foresight to sketch out this narrative well in advance, but thanks to the generous budget provided by Sega—$47 million at last count—his working environment must have discouraged thinking small. The first installment of Shenmue establishes the story of a young man named Ryo out to avenge his father's death and retrieve a mysterious artifact from the enigmatic Lan Di, and stands as the only chapter of the story to come into being as intended. And, unsurprisingly, Shenmue feels like the beginning of a story, one that barely allows its lead to achieve any meaningful goals. At best, the first Shenmue is the story of a man in search of which way a boat went.

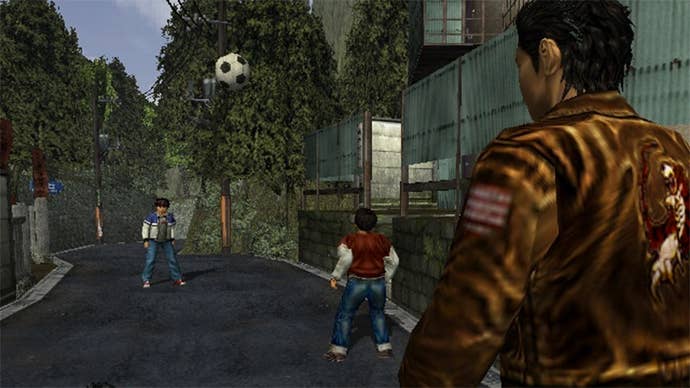

Even so, Shenmue's focus on mundanity offered a significant amount of appeal—remember, it launched just as The Sims taught us the sick pleasures of paying fake bills and queuing up bathroom breaks for our tiny avatars. Its world offered a level of unnecessary detail that's rarely been seen since: Even if you couldn't interact with every item you found, the contents of drawers, cabinets, and shelves could be inspected thoroughly. In addition, Ryo can nurse a kitten back to health—an act with no real purpose outside of the cuteness factor—collect capsule toys, play authentic Sega games at the arcade, and engage in several other pointless activities that didn't help the game's pacing, but gave the city of Yokosuka a sense of richness atypical for a video game backdrop. This slavish devotion to capturing the reality of 1986 Japan definitely didn't help the efficiency of Shenmue's production, as lead programmer Tak Hirai points out in an interview with 1UP.com.

"There were a lot of things that didn't make it into the game," says Hirai. "The hardest thing, and it doesn't even show on the screen, was the phone cord... The phone cord wasn't even showing up on camera, but [Suzuki] insisted on making it look realistic. I even made an eight-minute video presentation for the phone cord, but it didn't make it into the game."

Of course, the novelty of recapturing mid-80s Japan didn't hold the same appeal for an American audience. Though the beginning of America's short-lived anime boom had done its best to inform a young, gaming audience about Shenmue's country of origin, the late-90s U.S. perspective of Japan was that of a strange island that gave us sushi, karate movies, and tiny electronics. To soak up American dollars, Shenmue would need a thoughtful English localization capable of easing a foreign audience into its unfamiliar setting. Unfortunately, the sheer size of Shenmue's script—which includes fully voiced lines for every NPC—stood as an enormous challenge, especially for an industry just discovering the benefits of quality localizations.

Questionable casting decisions also dragged down the English localization, especially that of Corey Marshall as Ryo Suzuki. Marshall had no prior acting experience, but landed the job due to Suzuki's insistence that the voice actors resemble their characters—presumably for the type of cross-media promotion that's common in Japan. Marshall's poor performance, combined with the game's wealth of inexplicable line-readings, present an unintentional layer of humor that lends the English version of Shenmue the cheesiness of an ancient Godzilla dub.

In an interview with Hardcore Gaming 101, Jeremy Blaustein (who's worked on the localizations of Metal Gear Solid, Snatcher, Silent Hill 2, and many others) discussed the difficulties of this huge, expensive undertaking: "I've done a lot of these projects, and a lot of the times we've talked about my past work I've complained about how the budgets are low, and there isn't enough money, and here's a case where they made so many mistakes in the opposite direction. There was poor management and too much money thrown at it. It was rushed, and I know enough about games to know you're unlikely to get a consistent product. You have bits of it that were translated well, but there were probably 20 translators touching it, would be my guess. And with that many translators, working on that many characters, with a story that diffuse, you're going to have huge problems with consistency, huge problems with the story, huge problems with characters speaking."

It may sound arrogant to insist that Shenmue needed to appeal to Americans to find success, but that isn't the case at all. To be a success, Shenmue needed to appeal to everyone. Though its sales would have been considered a victory for Sega in any other case, the game's massive budget—now just a drop in the bucket compared to what's spent on AAA development—ensured that only an impossible amount of profit would have made Shenmue's production financially worthwhile. Just six years later, and you can see Sega directly apply the lessons learned from Shenmue to the Yakuza series. Though Yakuza features a Japanese setting and characters, it uses the touchstone of organized crime to lure in an audience who normally wouldn't be interested in a story completely divorced from America. And for its initial launch in the United States, Yakuza featured an all-star cast, with Michael Madsen, Mark Hamill, and John DiMaggio, amongst others. Later, Sega would realize gamers interested in playing very Japanese games probably don't mind if the characters actually speak the Japanese language.

In retrospect, it's difficult to understand just how Sega couldn't have prevented the failure of Shenmue at some point along the way—even if they had to kill it. But, knowing how much money they sunk into the production, Suzuki's pet project seemed to exist as an all-or-nothing gambit for the company, one that could possibly prove their relevancy and keep them solvent in the cutthroat world of gaming consoles. Thankfully, Suzuki has recently come out of hiding—like Hironobu Sakaguchi before him—occasionally tossing out a casual remark about his possible interest in continuing the Shenmue series, even if this does seem like the least likely thing to ever happen. Should the series remain stalled out forever, Shenmue will continue to exist as a testament to the plucky spirit of Sega, who decided to go out with a bang, when seeking the safest, cheapest way to stay out of the red would have been their best option.

But would that business strategy have given us the story of Ryo, the story of an honest man in search of black cars and sailors? I think not.

Most images courtesy of Hardcore Gaming 101.