Gaming Auteurs: Hideki Kamiya

From Devil May Cry to The Wonderful 101, Platinum Games' mastermind has always focused on making his audience feel as stylish as his outlandish heroes.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Games have so many moving parts, it's often impossible for one person's singular vision to shine through the many layers of content. But sometimes, we get lucky.

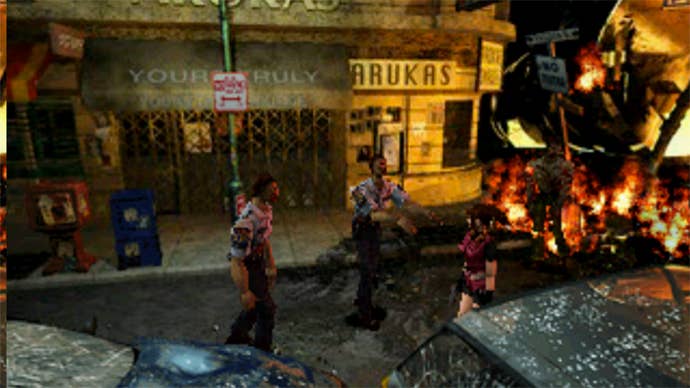

Though his projects vary wildly in premise, there's no denying the games of Platinum's Hideki Kamiya have a distinct character to them. Capcom might have kept this hotheaded developer on a tight leash for his directorial debut in Resident Evil 2, but, even when forced to strictly follow his predecessor's format, Kamiya makes his presence known. Resident Evil's first sequel ditches the original's hokey, Corman-style horror for a much slicker take on the genre (inspired by James Cameron and John Carpenter), and makes the series' trademark tank controls as manageable as they can possibly be by dropping in a few useful shortcuts. Though it lost much of the creepy, claustrophobic atmosphere that worked so effectively in the first game, Resident Evil 2 spoke to its audience through action-movie theatrics, and this approach worked incredibly well—think of it as Aliens to the first game's Alien.

At their best, Kamiya's games make players feel as if they're putting on a performance. And in 2001's Devil May Cry—which felt like the first game to finally figure out fast-paced 3D action—showing off stands as an implicit goal. Though grading systems aren't unusual to see in a Japanese game, Kamiya takes this idea one step further by relentlessly judging players based on how "cool" they look at any given moment, rather than waiting for the end of a level to evaluate their performance. And protagonist Dante's be-trenchcoated, post-Matrix sense of baditude reinforces this focus on being stylish: Throughout the course of the game, Dante preens, poses, and spouts one-liners to a "camera" he shouldn't even acknowledge. In Devil May Cry, players become directors themselves, trying to get the best performance out of the main character, both for the display of onscreen acrobatics, and the practical rewards that come from playing well.

This whole "performance" metaphor would go from implicit to explicit with Kamiya's next game, Viewtiful Joe. This side-scrolling brawler literally sucks its protagonist into a series of movies—and this premise ties directly into its interesting mechanics. The player controls Joe, and also acts as a makeshift film editor, as the game gradually unlocks commands that let you slow down the action, fast-forward, rewind, and zoom in. And each of these effects changes Joe's abilities: Slow down time, for instance, and your punches and kicks hit much harder (because slow-mo beatdowns look so brutal in the movies). Again, Kamiya places a focus on performance, and, like all of his games, Viewtiful judges ruthlessly: the grade "C" stands for "Crappy," in case you were wondering what's expected of you. And Viewtiful Joe's responsive audience (which cheers when you perform well) serves as a constant reminder that you're here to impress.

Though Kamiya wouldn't return to the Viewtiful Joe series after its debut—not that it lived too long afterwards—he would carry one of its central elements into all of his future work. From Joe onwards, all of Kamiya's games allow players to manipulate time as a means making his video game protagonists look endlessly cool, while accounting for the fact that there's only so much our fingers and thumbs can do at once. So, in Okami, he puts time on the players' side by allowing them a limited window to freeze onscreen enemies and draw the proper symbol (in a battle system based on Japanese calligraphy) to attack them. Having to draw on enemies while they dance around—and with an imprecise analog stick—would be endlessly frustrating, but Kamiya communicates the Okami protagonist's godlike powers by allowing her to bend time to a certain extent. The player might see this time-stoppage in action, but from the perspective of the enemies, you're pulling off these complicated and stylish moves in quick succession.

Kamiya borrows this brand of time-manipulation mechanic for Bayonetta, and again, it serves to encourage the player to perform well. In order to enter Bayonetta's "Witch Time" mode, you first have to dodge an attack with split-second timing. Then, things get slow and swimmy, and you're given a handful of seconds to pound on enemies while they're mostly defenseless; this use of slow-motion allows players to pull off moves they never could if enemies had their full mobility. And because you're forced to dodge before dropping into Witch Time, Kamiya once again reinforces looking stylish—made even more apparent by the protagonist's array of bizarre, showy moves that culminate in hilariously gratuitous finishers. Play Bayonetta effectively, and you'll rarely drop out of Witch Time as you bounce between clusters of enemies—do it right, and it's hard not to feel like a total badass.

With The Wonderful 101, Kamiya keeps up his obsession with time a full decade after Viewtiful Joe. Though it may look like Pikmin from afar, 101 combines the drawing-focused battle system of Okami with Devil May Cry's fast-paced and highly technical fights. Touching the GamePad's screen (or the right analog stick) slows down the action so you can reform your team of tiny heroes into powerful new forms that fit the situation at hand. And, like in Okami, Viewtiful Joe, and Bayonetta, you're given a distinct advantage over your enemies, but only slightly. The Wonderful 101 may look like a kid-friendly game, but it's just as brutal and merciless with its ratings as any other Kamiya production. You can't clumsily brute force your way through enemies, because you wouldn't look good doing it—and Kamiya certainly doesn't want that to happen.

To date, Kamiya remains in the ever-shrinking group of big-budget directors whose games still feel wholly theirs. When you pick up a Kamiya game—or anything from his studio, for that matter—you should know what to expect: an absurdly flashy experience engineered to make you feel like a superstar, but only if you come to terms with the extremely specific and often-complex rules in play. Though the face of gaming has changed drastically since Kamiya's Devil May Cry introduced us to his particular brand of madness, he's continually honed his unique style, and we should expect to see the upcoming Scalebound as yet another expression of this director's philosophy. His games may have too much of a learning curve at times, but it's hard to point the finger at Kamiya when he has such honorable goals—after all, he's just trying to make us look cool.