From Zero to Hero: The Wind Waker's Strange Transformation

How a former black sheep of the Zelda series turned its reputation around.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In what now seems like The Bronze Age, I worked at a game store during the long lead-up to The Wind Waker's original March 2003 release. And since part of my job description included coercing customers into pre-ordering, I spent this period talking to countless strangers about Link's debut on the GameCube. And, about half of the time, my questions about their possible interest in The Wind Waker were met with either "Isn't that the gay Zelda?" or "That game looks gay."

Even though Link's sexual orientation hasn't figured its way into any of his numerous adventures to date, my manager came up with an ingenious way to sell The Wind Waker to those skeptical/possibly homophobic about the series' dip into the world of vibrant cartooniness: It was just like watching Looney Tunes! Never mind that Bugs Bunny kissed all of those guys right on the mouth, I guess. While The Wind Waker's pre-release period coincided with America's short-lived "anime boom" in what seemed like foolproof synergy, Link's makeover clashed with what many thought a next-gen Zelda -- or any next-gen game, for that matter -- should be.

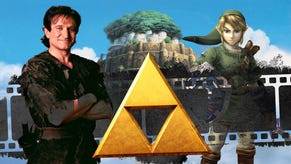

Nintendo had to come up with their own way to market Link's newest transformation, as well, since the distaste found in my game store -- expressed in purely teenage terms -- represented what seemed like a popular sentiment, or at least one from an extremely vocal minority. After Nintendo's 2000 Spaceworld trade show revealed the new Zelda game would feature a squat, goofy, and highly expressive child version of Link, thousands of gamers turned off their RealPlayers (or whatever the Hell we used to watch videos back then) and made thorough accounts of their disgust on the Internet. The promises of the '90s were supposed to be coming true on this new collection of consoles, and Nintendo had used the GameCube to plop a wide-eyed Link into a thoroughly non-gritty world? And as a Powerpuff Girl, at that? No doubt Zelda fans who thought realism was the yardstick for quality fled to the PS2, XBox, and even the Dreamcast, sure that Nintendo had lost their damned minds.

Though Aonuma and Miyamoto didn't budge from The Wind Waker's anime-inspired visual design, the squashy-and-stretchy Spaceworld Link's design became a little more conservative. And, to get the reluctant on board, Nintendo used a timeless strategy: giving away free stuff. Gamers who pre-ordered The Wind Waker at selected stores would receive a GameCube disc featuring The Ocarina of time, along with a brand new "Master Quest" that remixed much of the original game's content. Time passed, and, looking at The Wind Waker's various reviews on Metacritic, it's hard to believe a scandal even happened. Outside of a few common complaints regarding pacing, the gamers who didn't run screaming in terror from the prospect of an interactive cartoon found The Wind Waker to be another solid installment, and one that ended with the hint of a new direction for the Zelda series. (Okay, I guess we were still naive in some respects.)

Since then, we've seen the return of The Wind Waker's art style, but only in the DS games, where the effect of colorful, smoothly animated characters lost something in the translation to this spunky little handheld. Just as moviegoers hold a bias against traditional 2D animation in comparison to CGI, Nintendo has recognized gamers' preference for a Legolas-like Link, as seen in every Zelda console sequel to date. Skyward Sword might have paid some lip service to The Wind Waker with its baby steps towards impressionism, but the lack of serious changes to Zelda since The Wind Waker shows that Nintendo learned that gamers don't handle change well -- and let's not forget, The Wind Waker surfaced just a few years after Majora's Mask, which stood as the most disruptive installment since 1988's The Adventure of Link.

With this troubled history behind it, The Wind Waker's newfound relevance strikes me as one of gaming's oddest -- and most heartwarming -- stories of redemption. Make no mistake, though; Nintendo still isn't entirely confident in The Wind Waker. While they're using the HD remake to boost sales of the flagging Wii U, this new edition comes with one major caveat: its formerly bold, flat designs have been "improved" via the various technical tricks created within the last ten years. And while shaders galore certainly give The Wind Waker's visuals a lot more "texture," they still serve to undercut the original's design sense -- which is why the characters look more like Rankin-Bass stop-motion figures on the box art than the thick-lined cartoons of the past. As someone who played quite a bit of the Wind Waker in HD a few years ago via emulation, a minor bump in resolution is really all it takes to make this gorgeous game hold its own against contemporaries.

I'm hoping The Wind Waker HD catches the attention of a few more people this time around, because its look -- even in its compromised state -- deserves more than just a few portable games. And in terms of design, The Wind Waker felt like the last time a Zelda game wasn't afraid to let me roam without guidance. Complaints about endless sailing aside, there's still something magical and unequivocally Zelda about finding yourself in the center of a vast ocean, and being allowed to explore every corner of it at your leisure. Even if floppy haired Link never sees the light of day again, we can at least hope Nintendo remembers what made his GameCube adventure feel so boundless and free.