From DLC to free-to-play: a brief history of everything you love to hate

Ports. Platform exclusives. Microtransactions. Horse armour. Refresh yourself on the ins-and-outs of all the things you love to hate.

DRM

Tracing the history of DRM in gaming is difficult, because the phrase "digital rights management" applies to a variety of concepts. The basic definition is a technology used to control the use of digital content and devices after sale - and that can mean a lot of things, from preventing you from copying or sharing the content, to blocking installs, to limiting use.

Usually when we're talking about DRM in games we mean copy protection: something that prevents you from making copies of the game that other people can play. By this definition, DRM is almost as old as gaming itself. Although some games were (and are) freely distributed, most have been commercial enterprises. Many early computer games had activation keys (although you did not need to access the internet to use them) or passwords included in the manual or game packaging, for example.

The pièce de résistance of unpopular DRM is persistent online authentication – what we call "always-on DRM". Having to always be connected to the internet makes sense for an MMORPG or multiplayer-only game, but in something like Diablo 3, which you might want to play offline and alone, it can be a pain in the butt.

Pirates always found ways around these kinds of methods, as they do around every kind of copy protection eventually, but they didn't really inconvenience legitimate end users. It wasn't until DRM started to be annoying to regular joes that it acquired its negative reputation.

Today, there are several forms of DRM that users jack up over. Examples include those that limit you to one install (especially the draconian ones that mean one ever, rather than one at a time!), which is disappointing for those who grew up hosting LAN parties with one copy of a game, for example. Games that require you to install and fire up an external client, like Games for Windows Live or Uplay, or connect to the internet every time you want to play, are also frustrating, for obvious reasons.

The pièce de résistance of unpopular DRM is persistent online authentication - what we call "always-on DRM". Having to always be connected to the internet makes sense for an MMORPG or multiplayer-only game, but in something like Diablo 3, which you might want to play offline and alone, it can be a pain in the butt. Taking your laptop with you on holiday? No WiFI in your dorm room? Tough.

Several factors have contributed to help soothe these headaches. First, publishers have responded to backlash to annoying DRM by backing off the most unpopular versions, as well as trying to use more reliable, less intrusive technologies. Second, living in such a connected age means that you're less likely to be unable to activate a new game, and as one-time online activation is such a common solution, you won't have too much trouble.

This ill-defined sea of rights and counter-rights was one of the main reasons gamers reacted so badly to Steam. Yes, Steam! Good Guy Valve was once considered a huge threat to gaming.

What's really interesting about DRM, though, is the invisible side: who owns the content you're using? You paid for it, sure, but does the content provider have the right to take it away whenever they want? Can you sell it on to someone else if you're done with it? Do you have the right to make copies?

Copyright is such a complicated issue, and laws vary considerably across territories, so that the answers to these questions are not clear - and change year to year. The EU recently ruled that consumers do have the right to on-sell digital content, which has thrown the cat among the pigeons a bit, but we're yet to see the consequences.

So back to the history lesson for a bit: this ill-defined sea of rights and counter-rights was one of the main reasons gamers reacted so badly to Steam. Yes, Steam! Good Guy Valve was once considered a huge threat to gaming.

Some of the fear surrounding Steam's inception had to do with its novelty; Valve saw the future years before anyone else, and many gamers simply didn't believe in its vision. Downloading full games on a regular basis? Servers that stayed up consistently? Surely such a thing wasn't possible.

It obviously was, and after a rocky launch Valve proved it. It wasn't the first digital distributor but its success really established the space, and as such, we can credit it for popularising DRM. Steamworks is one of the most popular gaming DRM systems in the world today, and it's so reliable and invisible that most gamers have forgotten it is any such thing. Of course you have the Steam client running all the time. Of course you activate games through Steam's servers. Why wouldn't you?

Some people still refuse to buy or activate games through Steam on moral grounds; that Valve has never exploited the weird technicalities of copyright law to take content away from players doesn’t change the fact that it shouldn’t have that power, they argue.

This was unthinkable, back in the day. Detractors expected the whole thing to collapse at any moment, taking everyone's libraries with it, leaving nothing to show for all that money spent. They argued Valve would use the power laid out in its EULA to ban consumers on a whim, denying them access to their purchases.

Some people still refuse to buy or activate games through Steam on moral grounds; that Valve has never exploited the weird technicalities of copyright law to take content away from players doesn't change the fact that it shouldn't have that power, they argue.

The upside of all this is the anti-DRM movement has produced some lovely bonuses. The Humble Bundle began as a cross-platform, DRM free scheme and while it doesn't always stick to that now, it supplies boatloads of cheap games, and exposure for developers who might otherwise go under the radar. Offshoot the Humble Store is a very indie-friendly way to buy games. And GOG remains staunchly anti-DRM - but owes a lot of its success to the popularisation of digital distribution through Steam.

Pre-orders

For the most part, gaming pre-orders are a relic of a bygone age. There was a time when games were significantly less commercially successful than (the one percent) are today, and publishers produced significantly less stock. Shops would only order in a small number of these until they were certain a game was going to be a hit, and so, on launch day, you might toddle down to your local bricks and mortar only to find that there were no Mega Drive copies of Mortal Kombat left.

In those days, pre-orders partially existed to serve the consumer. You, the hardcore gamer, ensured you got a copy on release day - and your less forward-thinking friends got more of a chance of getting one, too, because the retailer might make a larger order. All the way up the supply chain, people had the chance to make more money by meeting demand.

Nowadays, pre-orders are very good for publishers - and retailers and distributors. It's money up front, and something to wave at investors. It still helps manage demand. But the thing is: there's no supply issue any more. When was the last time a shop sold out of a standard edition of a game? And if it did, would you not just get on the internet and find a copy somewhere else nearby?

In the digital distribution age, there’s no consumer benefit to pre-orders, especially if a game doesn’t allow pre-loading. The benefits of pre-ordering a physical copy pretty much boil down to "may or may not arrive on or before release day".

In the digital distribution age, there's no consumer benefit to pre-orders, especially if a game doesn't allow pre-loading. The benefits of pre-ordering a physical copy pretty much boil down to "may or may not arrive on or before release day thanks to the unreliability of the mail".

Nowadays, except in a small number of cases like limited-run localisations (think Yakuza 4, or NIS America and Atlus games, for example) catering to niche genres, they're almost entirely about everyone but the consumer. I suppose you could argue that anything that's good for the industry benefits us in the end, but to rebut this point I submit the following: Aliens: Colonial Marines.

Actually, Aliens: Colonial Marines has probably turned out to be a good thing for all of us. Consumers and press alike are far more wary of misleading demos and marketing materials. Now that Sega is forking out 1.25 million to make a false advertising case go away, publishers are likely to be less complicit in deceiving consumers.

Despite this little obstacle in the path of promotional bullshit, there's a strong argument to be made that pre-orders are quite bad for games - whereby games we mean the works of art and craft you play - not the money making machine. When games are primarily sold on marketing hype and pre-release expectations rather than critical response and word of mouth, there's always the chance the end product will be a bit balls. The publisher has reason to spend more on marketing than on making sure the product lives up to it.

Since they're not especially good for us, and they're definitely good for the business side, pre-orders are, naturally, held in disdain and suspicion by some gamers. Here's Jim Sterling, eloquently waxing lyrical on the subject of why modern pre-orders are so unpopular:

If you've made up your mind that pre-orders are bad, then pre-order incentives go hand-in-hand with them, skipping merrily down the highway of horrors. It's hard not to pick on Sega when it made what sounded like one of the very best parts of Alien: Isolation a pre-order incentive, so here's Jim Sterling again. He really doesn't like pre-orders.

Paid DLC

Downloadable content is a tricky business. It has its roots in the time-honoured traditions of PC gaming, and it was only when consoles got in on the action and the internet came into play that things went south.

Add-on content makes a lot of sense from a business standpoint; you've just spent an amount of money producing a huge number of assets and either building a new engine or monkeying around with an existing one. Why not leverage that effort and investment to just make a bit more of the game you've already released? New story, characters, locations, systems and features don't come cheap, but compared to a whole new production they're laughably affordable.

From a consumer perspective, paying a smaller amount for more of what you liked isn't a bad deal. Unfortunately there are multiple ways for everything to go wrong, and they've all have happened on multiple occasions.

Even if your game sells well the profit margins on triple-A is not always significant enough to fund the next project (and getting worse all the time) let alone please shareholders. A few popular add-ons can make up the shortfall. From a consumer perspective, paying a smaller amount for more of what you liked isn't a bad deal. When consoles got hard drives, it made sense to bring the expansion or add-on business model to them, and since most gamers have an Internet connection, developers and publishers didn't even have to weather the expense of a big boxed re-release, and could make smaller slices of extra content.

At this point it's all sunshine and butterflies and capitalism at its best. Unfortunately there are multiple ways for everything to go wrong, and they've all happened on multiple occasions.

The first problem is not exclusive to DLC by any means, but was especially prevalent and egregious early in the last generation: lack of value for money. If you pay one third of the cost of a game for DLC, you expect it to provide about one-third of a game's value, right? It's taken quite a while for DLC prices to standardise at a level (some) people are happy to pay, but before we got there we had all sorts of disasters, most famously Oblivion's Horse Armour.

That companies have the right to make extra money from add-on content is not in dispute. But that some companies have bollocksed it up in ways that seem really exploitative of the consumer is also not in dispute.

The second problem is definitely a DLC issue: the perception that content is being "held back" to make extra money. There are a couple of ways this can manifest. There's microtransactions that nickel and dime the player hoping for a complete experience. There's story content that arguably ought to have been part of the main game, as with Asura's Wrath story conclusion or Dragon Age: Origins characters. And then there's content that is so much a part of the base game that it is on the bloody disc, as with Street Fighter x Tekken.

That companies have the legal right to make extra money from add-on content is not in dispute. But that some companies have bollocksed it up in ways that seem really exploitative of the consumer is also not in dispute. Whether companies can charge you extra for content included on a piece of physical media you've already purchased is definitely open for debate.

Season Pass

A season pass is, essentially, a DLC pre-order. Publishers commit to producing a certain number of content packs, and gamers agree to buy them all at a discount off the full ticket price. While saving money is a good result for those who grab all the content anyway, season passes combine most of the negative aspects of pre-orders and DLC both. Refresh yourself with the sections above.

The season pass is so common today that it's hard to remember what a recent phenomenon it is. The specific phrase "Season Pass" was popularised by EA, but it was actually Rockstar (another case of "yes, Good Guy [company]" which kicked the idea off with 2011's LA Noire and its "Rockstar Pass".

While saving money is a good result for those who grab all the content anyway, season passes combine most of the negative aspects of pre-orders and DLC both.

The idea quickly took off, and you can see why - it's an added revenue stream on top of the game's launch sales, which looks good to investors; helps fund development of DLC which will later generate more income; and locks users in to playing the game for a relatively long time, something publishers get super excited about - although GameStop hates it.

Before the end of 2011, Microsoft and Warner Bros. were both on board, and it wasn't long before 2K, EA, Konami, Microsoft, Namco Bandai, Sony, Square Enix, Ubisoft and Warner Bros. had joined in. I doubt there's any major publisher that hasn't produced at least one, now.

One of the most interesting aspects of the history of the season pass is how the name evolved. At first publishers made an effort to come up with a name for it, usually Something Capitalised to indicate it was a proper noun, in an attempt to hide the fact they were jumping on a bandwagon. Nowadays we mostly just call it a season pass, lower case, and have done.

The season pass concept suffered a little bit by being lumped in with EA's super unpopular Online Pass scheme, something Sony also toyed with for a while, but these were very different ideas. Unlike the unpalatable online pass, season passes have lost most of their notoriety now, and only a few dissenting voices speak out against them - which is not necessarily a good thing, I should add. See "DLC" and "pre-orders" above.

Free-to-play

Free stuff is always good, right? Not in Gamer Land, apparently. Free-to-play is so derided that it has repeatedly been called a "cancer" on the industry, despite the fact that it's minting it for many developers who might otherwise just not exist. Free-to-play is so hated that when team Fortress 2 was made free, one of the chief complaints was that now the riff-raff could play.

Wow.

Free-to-play games kicked off in the 1990's, when internet culture was just starting to blossom. Casual browser games were among the first to adopt a "maybe you'd like to pay for some extras because you are time poor or money rich?" model. Some memorable examples include Runescape, MapleStory and Neopets (which seems to be in trouble now, by the by).

Thereafter F2P really took off in South Korea, Russia and a couple of other territories dramatically under-served by the west, and continues to mint it hand over fist in those regions. The amount of money these titles started bringing in naturally attracted the attention of the rest of the industry. Experiments abounded, and continue to this day; Riot Games seems to have nailed it with League of Legends, but EA cancelled Dawngate and Command & Conquer before full launch.

There are so many success stories though, both in the west and internationally, that free-to-play isn't going anywhere. Many hugely successful mobile, social and casual games are free-to-play, and most MMOs, unable to compete with the few remaining subscription titans, have found great success by converting.

One of they key factors in free-to-play's abiding unpopularity among a vocal subset of gamers is how the business model is implemented. It's a hellishly delicate dance. Be too generous and you'll make no money, because most of us will go to the wall rather than pay for anything we can get any other way, and there are only so many whales to go around. Be too stingy and you'll be seen as ripping players off with pay-to-win schemes. Even Riot and Valve have been accused of shenanigans, and the new wave of MOBAs will surely come under fire if they use the same business model.

Platform exclusives

There's nothing in particular wrong with platform exclusives in general. Companies pour millions of dollars into R&D and manufacturing to bring hardware to market, and exclusives are another way it encourages install base growth in the hopes of bringing more third-parties to the platform - which is where a lot of those costs are recouped. First-party exclusives represent an investment in a platform.

No, what bothers people about exclusives is when they cut out an existing fanbase. The most memorable example right now is Rise of the Tomb Raider. The Tomb Raider franchise first really took off on consoles on a PlayStation platform. When games started coming out for Xbox, that was all for the good: as long as we didn't have to deal with dodgy ports (see next page), there's no reason beyond full on mental fanboyism to deny games to people just because they can only afford one console.

When Microsoft secured an Xbox exclusivity deal for Rise of the Tomb Raider, though, that was a different matter: suddenly a bunch of PlayStation fans were told they could either buy a new console, or miss out. It's a timed exclusive, of course, so nobody will miss out forever (except maybe Wii U owners, but gosh, that's a tough sell all round), but if you've been playing Tomb Raider games for two decades suddenly having to wait a year (or whatever) feels like an insult.

Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo have all been guilty of securing exclusives, and often the end result is quite good - more money to build a better quality game, extra goodies for players on one platform that don't take any resources from the core game everyone gets. In reality, having to wait an extra 12 months for a game isn't that much of an ask, and happens all the time when developers can't afford to focus on more than one platform, with no backlash. But by gum, it makes people angry when it's announced ahead of time.

Ports

Nobody has any objections to games releasing on their platform of choice - but everyone objects to the game they get being not as good as the game someone else got. When a game is "ported", it means it has been developed for one platform and then adapted for another - and regardless of how this works out, the fact that a game was not developed specifically for a particular platform gives some gamers the heebie-jeebies.

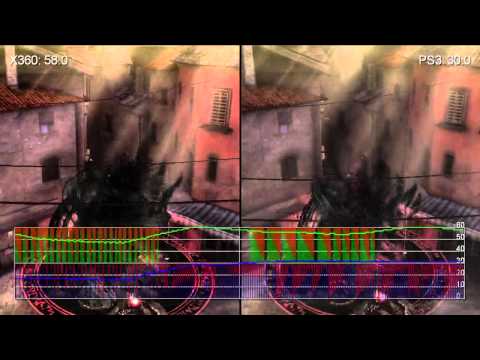

Sometimes they're justified. The differing architecture between platforms can sometimes mean it's very difficult for developers to make a game work well on more than one of them. Back at the beginning of the PS3 and Xbox 360 era, there were few middleware tools for the PS3, and its highly unusual architecture meant many games were developed with Xbox 360 in mind and then ported to PS3 - poorly.

The PS3 isn't the only culprit, of course. Although it's easier to work with than the PS3 in this regard, the Xbox 360 doesn't have as much in common with a PC as the PS4 and Xbox One does. Since by the end of the generation there were loads of middleware tools developed for PS3 and Xbox 360 alike (to avoid the problems described in the paragraph above), it was easier for developers to make a game for console and then port it to PC. Lazy PC ports, with improper keyboard and mouse support (to name just one possible disaster), are unfortunately more common than we'd like - and fail to take advantage of the PC's potential for more powerful hardware with additional graphics options and customisation.

Cross-platform development is generally good for everyone, and the backlash against Square Enix for granting Microsoft a timed exclusive on Rise of the Tomb Raider just goes to show how unpopular the alternative is.

Porting isn't a bad thing, necessarily; not every platform can be lead. Bad ports, on the other hand? Not only worth a bit of disgruntlement, but guilty of tarring the whole cross-platform movement with its filthy brush. Let's not have any more of it.

These accounts are by their nature brief, and this list is incomplete; loathing is a subjective thing, and changes over time. A few years ago "multiplayer" might have been one of the inclusions! Let us know your own pet hates.