From Busted Teeth to Broken TVs: The Oral History of Tony Hawk's Underground

The road to creating Tony Hawk's Underground in under a year was a wild one. We talked to the rebellious developers who made it.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

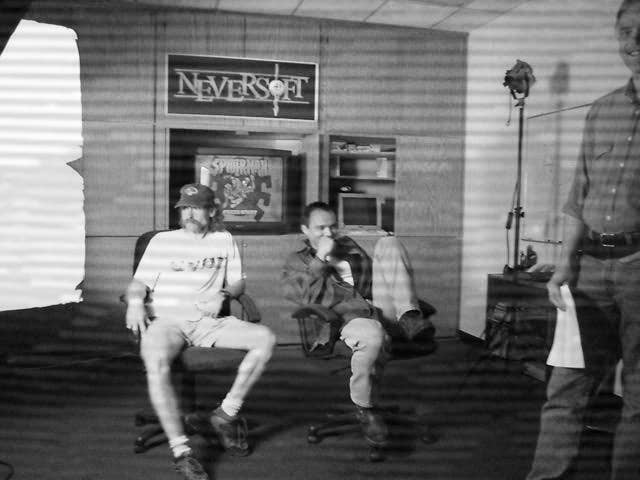

When it came time to make a game about becoming a pro skater—not simply just racking up combos—all developer Neversoft had to do was draw inspiration from the office building it was throwing TVs off of.

Ask the people who worked on it, and they'll tell you Tony Hawk's Underground is a cult classic. It's often overshadowed by other games in the series, such as Tony Hawk's Pro Skater 1 and 3, which are both regarded as some of the best games of all time. They'll also tell you that despite the popularity of those other games, Underground is their personal favorite.

When it came to Underground, developer Neversoft couldn't be stopped. Four games into a massively successful franchise, they saw an opportunity to change the formula, to plant a new flag in the genre it helped create. And so they did just that.

Developed in just under a year, Underground saw a departure from the formula that made its series so successful. It changed a proven formula by allowing, for the first time, players to get off their skateboards, walk around levels, interact with vehicles, and climb buildings. It also introduced a story mode, telling a rags-to-riches story of what it was like to become a professional skateboarder.

If anything, it was a more honest game to its creators. For a wild, hard partying, hard-working group of young developers, skating and skate culture was a cornerstone of the company. Neversoft lived and breathed skateboarding. They made skate culture their entire being and lifestyle and, in turn, fed it back into Underground.

This is the story of that game. Talking to a dozen ex-Neversoft employees, we learned about how larger-than-life personalities, insane hijinks, grotesque injuries, unrivaled passion, and machine-like work ethics all came together to try something new. Along the way we also learned about Neversoft, a team who were once a force to be reckoned with in the industry. A team who earned the right to do whatever they wanted by working as hard as they possibly could and, of course, unabashedly playing hard too.

From throwing TVs off roofs, breaking teeth, working sixteen hour days, and living the skate lifestyle Neversoft was adapting, the year that produced Underground was bombastic and dangerous. But perhaps most importantly: it was artistically invigorating too.

"Well, What Can We Do?"

Four years and four games into the series, Neversoft was ready to change the Tony Hawk formula, which meant walking away from the tried and true direction of the Pro Skater series, a direction now being imitated left and right by other action sports games. Feeling it had few places left to go, Neversoft started talking about what it would be like to add a story to its fifth iteration, what that would look like and who it would star.

Dana MacKenzie (UI artist, Neversoft): We were sitting down at the board table one day, just chitchatting … [about how] the whole create-a-skater system [from Pro Skater 4] was really, really strong. There was so much customization you could do with it, you could come up with thousands of different types of characters and it was really robust. So we came up with this idea of like, "Why don't we pitch something? What if we used create-a-skater as the basis for the next game. Instead of just having a bunch of pros, what if you can go in there and basically create whoever you want and then take them off and skate and whatnot?"

Nolan Nelson (lead character artist, Neversoft): We were looking for ways to make the create-a-skater feel more like you were creating your avatar. … It was just something we wanted to try.

Dana MacKenzie (UI artist): That was the basis of what became Underground.

Scott Pease (producer, Neversoft): People would do market research and they would say, "Would you like it if you could put yourself in the game?" And people would say yes. So it was kind of responding to what people wanted. People wanted to feel like they themselves were in the game rather than playing a character. And when they were playing a character, then they want to make it feel like they were that character.

Alan Flores (senior designer, Neversoft): It was definitely a risk, but we felt that it needed a change. I think that in Tony Hawk 3, we were at a peak, it was sort of like a zeitgeist thing. I remember going into Best Buy the day [it came] out and seeing them just wheeling out a cart full of Tony Hawk games, and it's just flying off the shelves.

Then after that we did bigger levels, more involved goals for Tony Hawk 4. I think some of the best work we did as designers, both scripting and designing, was in Tony Hawk 4, but the game didn't really catch on as much as Tony Hawk 3.

Chad Findley (lead designer, Neversoft): I loved making the games, but you could tell it was starting to feel a little repetitive. Not just the fact that it was the same formula, [but] you could tell people were trying to bite at the game and do some copies of the games out there. It started to feel a little old. So it [was] like, "Well, what can we do?"

Jim Jagger (animator, Neversoft): I mean, I guess by that time, there wasn't a great deal [of places] left to go in terms of direction. By that time most of the tricks were kind of established with the revert, the manual and … the halfpipe transitions where you drop down in on the other side and the flatland tricks. But [at] that point it was like, "Where else can we go?" I think a storyline was the next logical step.

Chad Findley (lead designer): And Scott Pease is the man. … He's why Tony Hawk happened, and he's also a lot of why Guitar Hero worked for Neversoft. He was always like, "Leave nothing on the table and do the best you can." So we start talking about what can we do, and I'm pretty sure it was his idea [of], "Well, what if we really let the players out there who are starting to love this culture." You know, skate culture wasn't as big until these games started coming out, "What if we could bring the culture to these people and let them actually see what it was like to go from a nothing to [amateur] to a pro?"

Scott Pease (producer): I think it was just a natural evolution. A lot of things on the Tony Hawk series, they just evolved over time. We didn't want to stay with the same formula year after year, we felt like we should keep trying to push it forward. [In] Tony Hawk 4 we went to the pseudo-open world [with] wandering around, talking to characters, and getting little special missions. A lot of that content was developed by talking and interviewing the pros and trying to make interesting goals that played off their own personal history. That was our first dip into trying to tell a little more story in our games.

Joel Jewett (co-founder, Neversoft): It was pretty simple [laughs]. Add the story, see how you can work that into the thing. I mean, at that point in time, I guess it was like the third rise in skateboarding or something? There were a lot of people into skating, the culture was huge and we just tried to embrace that culture and make something that would be fun, entertaining.

Mick West (co-founder, Neversoft): I think it was fairly obvious because it's kind of, in a way, the Tony Hawk story. You think of people starting out just as street skaters in Dogtown and then working their way up, becoming pro and rich and famous and being able to do what they want and make money. So I think it was a natural fit, that story.

Chad Findley (lead designer, Neversoft): The number one coolest part for me making this game was I got to interview every single one of those pros for about an hour. … Because if you're telling the story about going from nobody to pro you want to get it right. My goals changed as I was doing those interviews. I learned so much working with those dudes and interviewing those guys. …

[When] I started off, I was like, "I want to make a great adventure game, Tony Hawk [style]," which is kind of stupid when I say it. But as I interviewed those guys, my goal changed to, "I want people to feel what it's like to be a pro, and to do what these guys did, live the life that they did and go through the hardships and the betrayals and all the stuff that they did." The stories they told, these guys are warriors. I just wanted people to experience that feeling.

Alan Flores (senior designer): And a lot of crazy stuff happens along the way, because that's what happens in a Tony Hawk game.

Mick West (co-founder): There was mixed opinions about how far we should go. Some people wanted to do much more story-based gameplay with a narrative.

Scott Pease (producer): I think some of the early drafts of our story were almost too grounded in reality. Joel was always pushing us to liven it up and send a guy to Russia [to] let him screw around and drive a tank [laughs]. Just to make it a little bigger and make it feel a little impactful.

Mick West (co-founder): We kept the core gameplay mechanic, so we knew we still had something that was fun. We tried to not add things that were too detrimental, like cutscenes you couldn't skip and stuff like that. We tried to make it so that if people just wanted to get into the game and play the game, then they could do that without this other stuff getting in the way, but at the same time expanding it to an audience who perhaps expected a little more narrative and context to their gameplay.

Chad Findley (lead designer): I imagine there was some [nerves] like, "S**t. Should we break it like this?" And, "We're going to tell a story?" But once we got into it, man, once we started just even throwing around the ideas, it was awesome. Like from the get-go it was awesome even talking about it.

Jim Jagger (animator): I do remember [when] Joel came out and said, "This game's going to be called Tony Hawk's Underground." He just did it at a Monday morning meeting, and I was like, "T.H.U.G., I like it."

Joel kind of looked around and was like, "Aw, yeah. Cool, yeah. T.H.U.G."

With True Freedom, Comes Great Responsibility

One could think after years of success, Activision, the publisher of the Tony Hawk series, might have some trepidation with Neversoft changing up its formula. Conversely, because of the studio's success, Activision more or less let Neversoft do whatever it wanted, even forgoing the more strenuous aspects of its greenlight process. According to those we talked to, Activision wasn't worried.

Joel Jewett (co-founder): Well, for starters, there wasn't even a greenlight process when they started working with us [laughs]. And we'd been doing pretty well without one, which we were not afraid to remind them of.

Alan Flores (senior designer): I think there was a greenlight meeting, but we never really paid any attention to it. They were going to put the game out regardless. We were going to do what we wanted.

Scott Pease (producer): They just left it to us, it was our baby. We just decided what we were going to do. Honestly, I think we just made their job easier, because every year they had to come up with, "How are we going to sell another sequel?" And as long as we were pushing boundaries and adding interesting new features, they always had something that they could market, [that] they could hang their hat on.

Joel Jewett (co-founder): A lot of times publishers, especially after you've had something that's super successful, are kind of like, "Ooooh, that won't work. Why would we change it?" But, you know, we'd made four skateboarding games already, they'd all [been] huge and everybody was on board to change it up.

Scott Pease (producer, Neversoft): Things have changed I guess over the years, but back then the Tony Hawk games were doing so well for Activision, and I don't think originally they ever expected them to do as well as they did. So as long as we were helping bring in some profit for the company, I think they really smartly went hands-off and said, "You guys are the creators, you guys create. We'll help sell."

Jim Jagger (animator): We did have a lot of autonomy, because I think at the time we were making the bulk of Activision's money. I think a third of their profits came from the Tony Hawk franchise.

Chad Findley (lead designer): We never disappointed. Joel, best boss I've ever worked for, he ran that company really well. He comes from a financial background, he made sure we never fucked up anything and that we always hit the numbers.

Jim Jagger (animator, Neversoft): If anyone came over in a suit, Joel would yell at them and intimidate them and kick them out, and then they'd leave us alone for a bit longer.

Alan Flores (senior designer, Neversoft): I've seen him make marketing people almost cry. There was one guy [from marketing], and he just reemed the guy a new one. The guy, I think he went out into the parking lot and was just yelling at himself. "They're always f**king mad! They're always upset, they're never happy! They're never f**king happy!"

Jim Jagger (animator, Neversoft): And then we'd deliver. We always got it done on time.

"We're Not F**king Around"

To understand the type of studio Neversoft was going into Underground's development, it's best to understand its founder, Joel Jewett. He's a man spoken of with reverence, fear, and respect by those who worked with them. As they tell it, of the studio's three founders—Jewett started the company with Chris Ward and Mick West—he truly embodied what Neversoft was known for being: a hard-working, hard-partying, anything goes type of place. His philosophies, attitude, and the way he ran his studio would be the cornerstones for a lot of the mantras that helped birth Underground.

Cody Pierson (animator): [Joel] was the embodiment of Neversoft. I don't know if people were attracted to him and gravitated around him, or if he [cultivated] that culture on his own, but he was the heart and soul of that company, and he was a f**king awesome person to work for. He was intense, he was fair, he would push people, he would look out for people; he was the patron of that company.

Chad Findley (lead designer): Joel, his goal was always, "I want you guys to be able to go home on the weekend, because I want to go home on the weekend and spend time with my family and hangout and drink beers and relax."

Our motto was "Work hard and play hard." Joel would say this: "We get in it, you sit in your seat, we're not f**king around. We work, get our hours done and then we leave. And we don't worry about it once we leave." That kind of attitude just really got distilled in us and we followed it and it proved that we could just get s**t done.

Dana MacKenzie (UI artist): As soon as Tony 4 was out the door he was like, "Screw that game, this game's going to be even better than that!" Like, sending a kid off to college: "Don't let the door hit you in the ass. Okay, onto the next one."

It was really cool because he understood the whole business mentality and that you always have to be on top of things. You have to [be] continually making a better game and making a better game. He wasn't going to just sit back and enjoy the success; he was going to always push for more.

Jason Greenberg (animator): Joel is the best boss I have ever had.

Dan Nelson (programmer): You were scared to f**king death of him, you were so afraid he was going to get p**sed at you. Because he has this look that he would give you, this gaze of death, and it would just shoot adrenaline through you if you fucked up or you told him something he thought was bullshit. … But then underneath that, you knew he actually gave a s**t. I've worked for a lot of guys now over the years, and [with] Joel, you genuinely got the feeling that he cared about you as an individual. He wanted you to succeed in your career, he wanted you to succeed in life. He didn't want to f**k you [over], he was going to be super fair with you. He expected you to be super fair back to him. He was going to treat you right.

Jim Jagger (animator): I remember when I left [the company, right before Underground was released], I sent [Joel an] email and was like, "Hey, Joel. Can we have a chat?"

He said, "Yeah, come to the office."

So I went to the office and I walked in. He had both feet on the table. He had a revolver in his hand and he spun the barrel, like flicked it in, pointed the gun at me and then said, "So you're quitting, huh?" …

I had this speech worked out in my head, but how do you get over that? [Laughs]