Friends in High Places

Eurogamer's Simon Parkin tells the story of Xbox Indie Game phenomenon Mount Your Friends.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The genitals were a mistake.

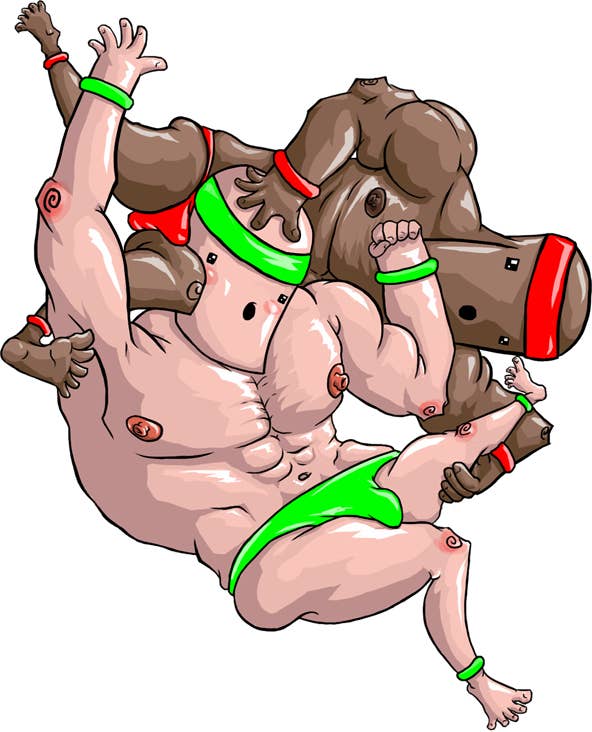

More precisely, the genital physics were a mistake -- after all, it's difficult to imagine any programmer plotting to make a character's appendage windmill around their groin like a sausage in a washing machine. But, for Mount Your Friends creator 28 year-old Canadian Daniel Steger, it was a welcome mistake. Since its launch earlier in the summer, this Xbox Indie Game has become the programmer's most successful release -- one of the most popular games ever on Microsoft's service -- and, arguably the first video game to find fame and popularity through penis dynamics.

"Meat-spin, as I like to call it, was a bug," explains Steger, who created the prototype for Mount Your Friends during a Toronto game jam, an event during which amateur and professional game programmers gather together for a few days to create video games on a particular theme. "This year TOJam was packed; around 400 Toronto game developers met up for the weekend to make games around the common theme of 'Uncooperative'. I was placed in the hallway next to my friends."

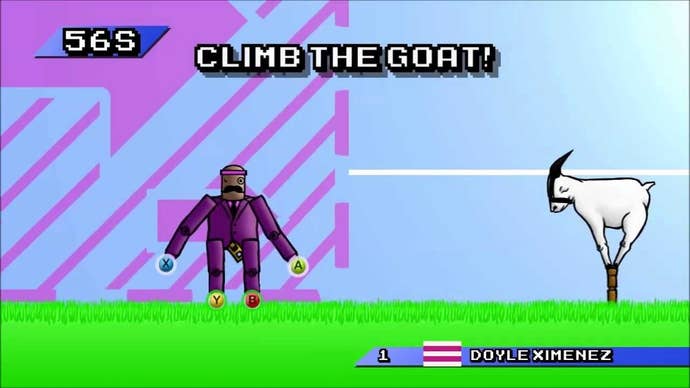

Steger -- one of the few developers to earn a living from selling Xbox Live Indie Games -- had low expectations for the weekend in terms of creating a sellable product. "Most TOJam games I make aren't worth talking much about," he says. "Even the ones I've gone on to sell have performed poorly." But Steger immediately had an idea that he thought would work well with the theme: a competitive game in which players took turns to create a tower of bodybuilders. Steger borrowed the control system from Bennett Foddy's QWOP, whereby four different buttons each control one of the character's limbs. Players must use a combination of inertia and limb-swinging to hoist their character up the sticky mound of bodies (all of which stand, inexplicably, on the back of a mountain goat). When a player's character makes it to the top, control switches to the next player, and so on until someone falls off or fails to reach the summit within the time limit.

"I had no idea how the game would end up, but I enjoy making physics games," says Steger. "When it reached a certain point I let a few people play. They enjoyed the game so much that their insistence to play began to impede my ability to finish it. So I knew that the game was fun. But it wasn't till I added the 'dongle' to each character's groin that it really took off." Steger had made it something of a tradition to add comically sized genitals to his characters in each game he made during TOJam. "After adding that, er, detail, a peculiar bug happened which can only be described as 'meat-spin'," he recalls. "It was spinning out of control to the point where I couldn't control my character due to the 'jitter'. When I saw the bug I collapsed. People started to gather around my screen to see what I was laughing at. When they began to join in I knew I'd hit on something special; I knew I was taking the game to Xbox."

Steger grew up in Toronto, born into a "nerd family" that encouraged him to learn how to use computers as soon as he was able to work a mouse. His father and brother taught him how to code so, when he elected to take a course in programming at High School he was far ahead of his peers. "Our final course project was to make a game," he says. "I asked the teacher if I could use more advanced libraries than our course taught, since I wanted to make a game with sprite graphics and sound. From there I spent inordinate amounts of time working on my game; far more than was needed to complete the course. I was just excited to be making a game from scratch."

This early success inspired Steger to pursue a university degree in software engineering. "I ran across a club full of game developers," he says. "We met, shared tutorials, and ran competitions. I volunteered to design advertisements to attract people to the club, as I was one of the few people at the time that enjoyed illustration. That said, most of my posters were very odd. My art style has always been fairly silly and joking in its style, so I often had very weird fake game characters put in my posters."

Steger continued to make games throughout university and, as soon as he graduated, began work on a commercial indie game. "The first game I made for money was a Scorched Earth-inspired title called Tank Strike for the Xbox Live Indie Games marketplace. It let me create a core engine and was a good starting game to get onto the market." Microsoft's service has been much maligned by developers, many of whom claim it's under-supported. Steger has a different perspective: "I saw XBLIG as a place with potential. The Xbox had a huge install base, and I didn't have to pitch to any publishers to get on the platform. XBLIG actually has a fair number of success stories. When you let everyone in, you're going to have a lot of failures, just as you do on mobile. There's no gatekeeper to guide developers away from bad ideas, for better or worse. But it allows some more interesting stuff through."

Following early success with Tank Strike, Steger was inspired to pursue more titles on XBLIG. To date he has released almost twenty games on the platform. A few have sold fewer than 100 copies, but his successes have made this a viable platform on which to build a career. "The majority of my games make the minority of my income," he says. "It's a hit-driven market."

Mount Your Friends was fully playable by the end of TOJam. Steger spent the next month adding features and tidying up the game. "I had a feeling that this game was 'special' before I released it," he says. "TOJam made me confident that the game was both challenging and humorous. I thought that it could be a big hit, but I also know I've misjudged games before."

The day after Mount Your Friends launched, Steger was certain he had made another of these gross misjudgements. "I assumed that I failed," he recalls. "The early stats were well below what I had expected and I didn't see much buzz about my game." But later that week the number of downloads for the game sky-rocketed. "YouTube happened," he says. "It started with notable YouTubers PewDiePie and UberHaxorNova and then quickly spread. I got to watch people I've never met having a blast enjoying the game. YouTube is a huge part of Mount Your Friends' success."

The game is well suited to YouTube's playthrough format, where presenters commentate on the game while playing. Not only does the visual humor make for compelling viewing, Steger's random name generator, which assigns each character a ridiculous name, adds an element of accidental absurdity. "One of my favourite YouTube clips is of when two players got a randomly generated climber named 'Hung Bellow'," says Steger. "When they saw the name the active player broke down laughing to the point that he barely was able to finish his turn." Steger capitalised on this success by introducing some of those YouTube personalities as cameos in the game for a recent patch. As sales multiplied, he took Mount Your Friends to Steam Greenlight, and within a few short weeks the game was accepted onto the service as a PC release.

Mount Your Friends is just one of a clutch of video games that find their humor not in scripts or planned cutscenes, but in the curious results of awkwardness and chance. Foddy's QWOP and GIRP as well as Young Horses Inc.'s forthcoming PlayStation 4 title, Octodad, are games that play with physical comedy in favor of scripted comedy. "Most of the time when we talk about humor in video games we reference Day of the Tentacle or Space Quest," says Steger. "These are authored experiences that require a strong writing background; in fact, the writing often takes precedence over the play. But I like humor that occurs as part of the mechanical systems. This is often overlapping with emergent behaviour in games but is an ideal I like to see in any kind of attempt by a game to inspire emotional response. Having the systems that the player is interacting with be part of that humor means that the player feels like they are being funny by playing the game, because they are making the humorous situations occur, as opposed to jokes being force-fed to them by a narrative."

Steger plans to stay on XBLIG for the foreseeable future ("at least, until the 360 becomes less viable to make a living on") and his success with Mount Your Friends has inspired him to continue to explore local multiplayer games, where players share a sofa to play, rather than co-operating or competing remotely across an internet connection. "I've started building a collection of local multiplayer games that I enjoy playing with my friends," he says. "Accessible but deep multiplayer experiences are a blast. There's been a renaissance in local multiplayer games in the indie space. The Yawhg, Nidhogg, BaraBariBall, Hokkra, TowerFall, Super Pole Riders and so on. There is something very special about this type of game. I hope we are seeing a resurgence of the form."