For Great Justice: A Partial Origin Story of Gaming's Original Internet Meme

A look back at our collective fascination with a threat in broken English, as an alien took possession of all our base.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Meme X Scene

The meme. It's everywhere, online. It has become the currency of the Internet, circulating in a fashion that BitCoin's creators can only fantasize about in their most avaricious dreams.

Evolutionary and cultural scientist Richard Dawkins coined the word meme back in the ’70s to describe patterns of behavior that circulate throughout a culture or society not by way of genetic dissemination but rather through leaning and imitation. Yet Dawkins' neologism languished in obscurity for three decades until finally being dragged to light by sheer necessity. When Hideo Kojima used the tagline MEME + GENE = SCENE to describe the themes in the Metal Gear Solid trilogy up through 2004's Snake Eater, the world collectively scratched its head. A decade later, however, the term has become common parlance online — as has the behavior which it describes.

Dawkins surely never expected his term to become such an integral part of global communication; memes transcend both mediums and culture, frequently escaping the Web in order to make their way into wider society as a whole. In fairness, Internet memes probably aren't precisely what Dawkins had in mind when he came up with the word all those years ago. Not only was the Internet a mere embryo at the time, gestating in the womb of academic and military computing, but online memes are almost exclusively born of amusement and comedy. The infamously humorless Dawkins has expressed bafflement at live memes, which have less to do with his vision of the concept (the propagation of cultural institutions such as religion) and more to do with grammatically challenged cats requesting cheeseburgers. Then again, that's perfectly in keeping with the original concept of the meme, which observed that ideas would evolve and mutate as they circulated. The meme memed.

Some corners of the Internet have latched onto the concept of the meme with tremendous enthusiasm, incorporating memes into their communication the way other people do emoji or acronyms like "LOL." Those memes tend to involve a highly specific concept, such as a "rage face" or an image template overlaid with a prescribed chunk of text in Impact font. Despite this trend toward commoditization, though, natural memes still burst into being from time to time: Jokes and ideas that spread throughout social media and beyond without being sparked by a conscious desire to manufacture a trend.

Needless to say, video games and online memes have a long and storied history together, and not always to everyone's liking. Nintendo of America's recent trend of incorporating memetic phrases and jokes into their English-language localizations have made some fans almost as angry as the company's habit of removing hints of racism and sexual assault from U.S. releases. Yet Nintendo was hardly the first to walk this road; quips about "massive damage" or "a winner is you" and other jokes born or popularized online have been appearing in game dialogue for a decade. And it's only natural, really, because video games and online memes have been kissing cousins for years, ever since one of the very first widespread Internet memes emerged from a video game.

All your base

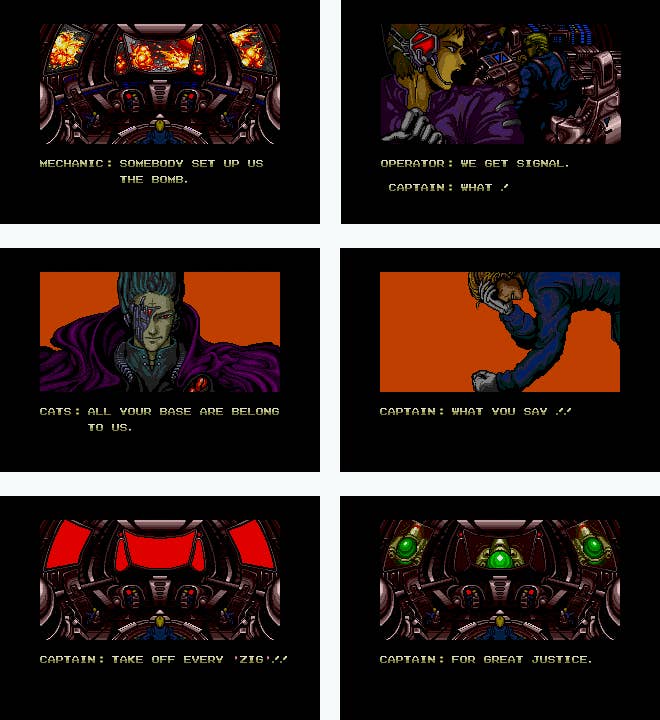

You may not know the name "Zero Wing," but you know the meme it launched, as adroitly as its doomed captain launched every Zig.

A competent but otherwise standard shooter developed by defunct studio Toaplan, Zero Wing was simply one of countless dozens of space-themed shoot-em-ups to appear on Sega's Genesis in the early '90s. The system didn't fare well in its homeland, where it was called Mega Drive, but you'd never know it to judge by the impressive number of shoot-em-ups that appeared on the console exclusively in Japan throughout its life. If anything set Zero Wing apart, it was the fact that it may well have been the most slavish imitation of Irem's classic R-Type ever put to silicon.

Zero Wing made its way to Europe but not the U.S., so for American gamers it flew almost entirely beneath the radar. What few knew of it generally had played its Japanese incarnation: American and Japanese cathode-ray televisions operated on the same NTSC standard while European TVs used an incompatible format called PAL.

It was the European version of the game that became famous, however. In its original Japanese, Zero Wing is simply a bog-standard R-Type clone, albeit one with a bizarre ending:

In Europe, however, the game's opening cut scene received an extraordinarily clumsy English translation. Grammatically awkward Japanese-to-English translations were hardly uncommon in the ’90s; on the contrary, good localizations were the exception at the time. Even so, Zero Wing's dialogue (such as it was) set a new standard for loopy, incomprehensibly translated text.

One early fan of the game was Brandon Teel, who learned of its opening sequence while running a site called Zany Video Game Quotes. ZVGQ's publication of Zero Wing's European intro, along with the game's more or less simultaneous promotion in several other online publications and forums, helped propel its opening cinema to infamy.

Teel's site had been one of several to spring up in the late ’90s to make fun of inept game localizations. This collective bemusement at clumsy English was already practically memetic within online gaming communities throughout the ’90s, especially role-playing fan communities. Console RPGs like Final Fantasy II (née IV) and Breath of Fire II suffered from the same laughable English that had appeared in NES games like Pro Wrestling (the origin point of the phrase "A winner is you!"); but where those mangled phrases had been limited primarily to intros and endings in the 8-bit days, 16-bit RPGs contained as much text as a novella, and some of them seemed to include a grammatical error in every single sentence.

"When I started ZVGQ, I was 16 years old," Teel recalled, "and much of my literary background had been Final Fantasy II, as it was known then. I had been captivated by the emotional core of that game's story, even past the awkward writing style. I think that started an interest in language, specifically the relationship between style and intent. I wouldn't have described it like this then, but I think that dissonance between intent and style was interesting and often really, really funny to me."

Where the era's online humor sites (such as Seanbaby and Homestar Runner) were content to riff on these text errors in passing, Teel decided on a more dedicated approach. Like many sites of that era, ZVGQ came into existence in large part due to the spread of console emulators and game ROMs. Legality aside, the promulgation of ROMs in the early days of the World Wide Web led to a remarkable amount of discovery within formerly obscure corners of the medium — and, subsequently, of sharing those lost treasures.

"I started the site because emulators had recently gotten good enough to play 8-bit and lower-end 16-bit games smoothly and somewhat accurately, and I was able to take screenshots of things I found interesting or funny in those games," Teel says. "I would post these screenshots as my signature on the message board I ran at the time, and had accumulated a fair number of them, so I started a small website on a free provider to show them off. Within a few days, James McKain, a friend of mine from that message board, had some webspace where he hosted a site about Macross, and offered me space on there."

Next page: "What you say!!"