Five Weird and Wonderful Nintendo Stories of Success, Failure and Sleight of Hand

Over its 126 year history, Nintendo has had its successes, failures, and sheer good fortune. Here are five stories about Nintendo games that you think you know - but you very likely don't know the half of.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Nintendo has taken a lot of stick this generation due to the unexpectedly poor performance of its Wii U console. Hands have been wrung, lamentations have been sung, and the way some people would have it, the 126 year old company is about to go down like the proverbial ship that it predates by a couple of decades.

But were those people to take a step back and pop a Prozac or two, they'd realize that Nintendo has been around for a very long time, and while it's true that things don't look great for the company at the moment, this is hardly the first time Nintendo has found itself in a bind.

Bearing that in mind, we thought it'd be fun to take a look back at some of Nintendo's more interesting hits and misses - the unusual stories that have helped make the company what it is today.

Nintendo Almost Deep Sixed by Radar Scope

Nintendo's history is defined by moments of crisis and the deft, almost desperate maneuvers that changed the course of its business for the better. We can look back to the GameCube era and observe how Nintendo stagnated in the face of the PlayStation 2 and Xbox, only to save itself with the DS and Wii. We can observe the heartwrenching launch of the Virtual Boy, which could have destroyed Nintendo's portable gaming business if the surprise success of Pokémon hadn't allowed the company to keep the insanely profitable Game Boy line running for another half-decade. We could even take into account the truly olden days of the company, when it bounced from one business venture to another in search of a hit. Eventually Nintendo found success as a toymaker -- a niche that quickly came to an end when the '70s oil crisis made the cost of manufacturing toys too expensive to be viable, pushing the company into arcade and video games.

Make no mistake about it, though: Nintendo's early forays into video games were anything but categorical successes. The company doesn't really like to venture further into its own past than the Famicom launch in the summer of 1983 outside of the occasional special edition hanafuda card set, but the fact is that the company's transition from toymaker to game manufacturer proved to be anything but smooth. Back in 1979 -- 35 years ago -- Nintendo's first major arcade push very nearly tipped the company over the edge of financial ruin. We think of the '80s as a decade dominated by Nintendo games, but in truth the company barely even made it to 1981.

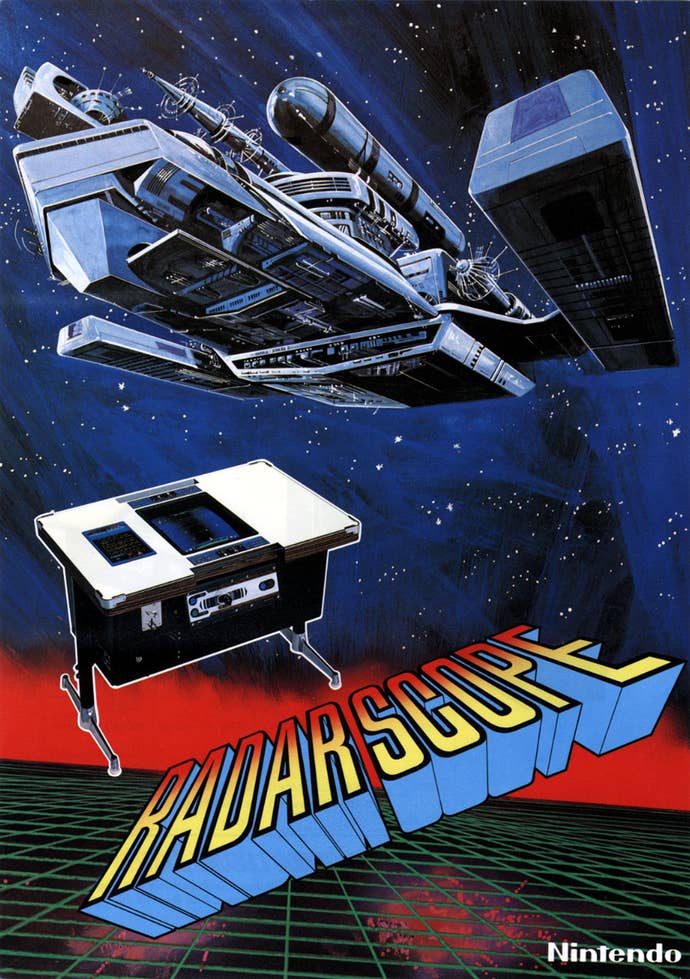

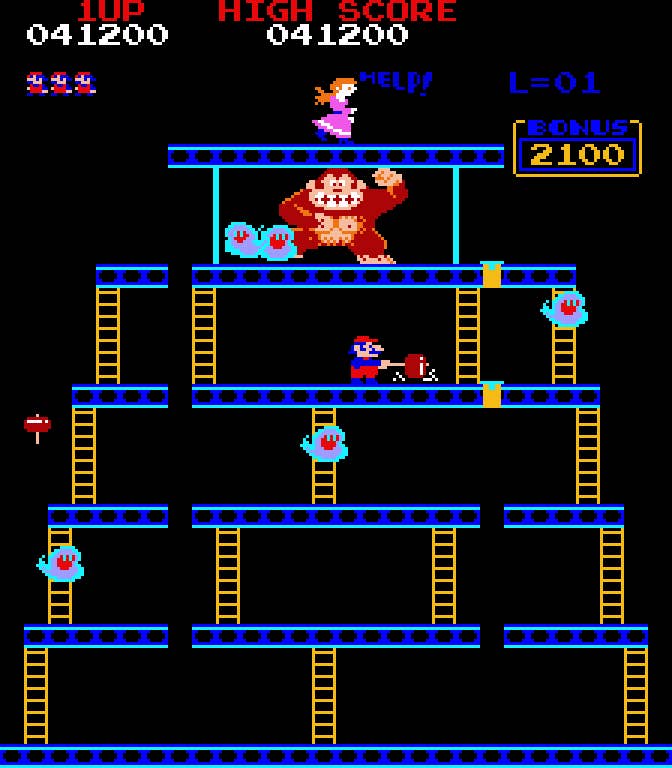

What happened? Nintendo pinned its hopes and dreams on Radar Scope, an arcade game in the Space Invaders vein. As in Invaders, Radar Scope placed players in control of a small ship at the bottom of the screen, sliding left and right while firing at advancing waves of alien marauders marching downward from the top. These games absolutely flooded arcades in 1979; Invaders had been a massive hit in Japanese arcades the year before, and as with Pong before it and Pac-Man soon after, the success enjoyed by such a simple concept inspired countless imitators.

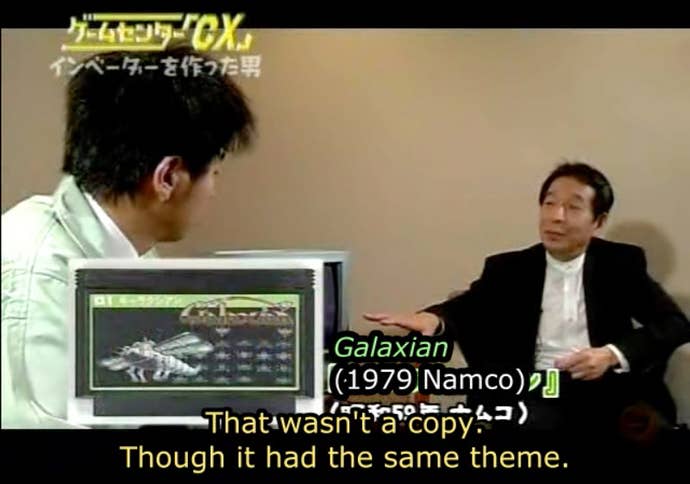

To its credit, Radar Scope belonged to the better class of Invaders rip-offs. The baseline Invaders clone simply copied Taito's creation without adding anything new or interesting to the mix, while the better ones tried to improve on what had come before. Games like Radar Scope definitely came across as derivative, but at least they had some ambition. Though Nintendo's project didn't live up to the high water mark of Namco"s Galaxian (a game Space Invaders designer Tomohiro Nishikaido cited as a great improvement on his own work in an interview on Game Center CX), it added some interest to the format with a cool visual twist: Single-point perspective.

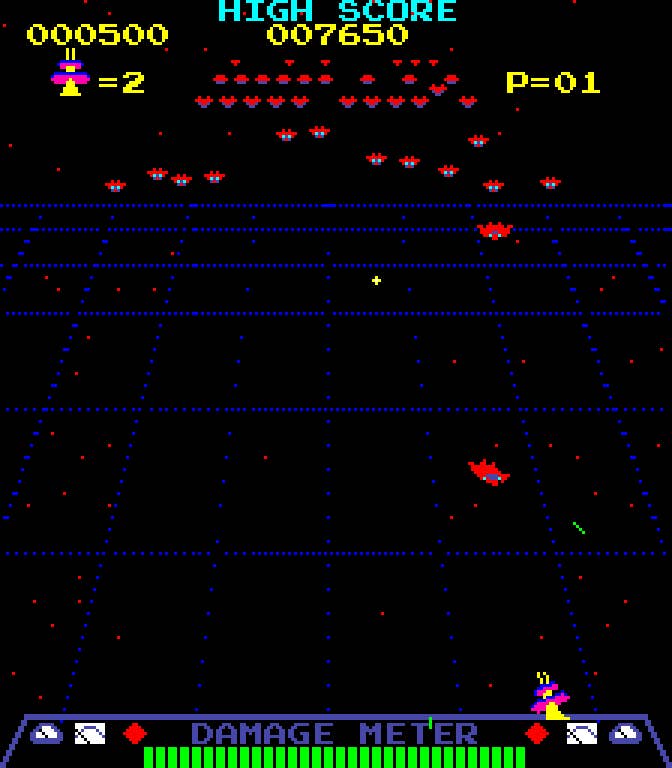

Unlike competing Invaders-come-lately, which presented their action on a flat plane, Radar Scope tilted the playing field "away" from the player, creating the sensation that the battlefield stretched into a vanishing point on the horizon and that the alien intruders were marching from somewhere in the distance. That the game featured such a crafty visual embellishment perhaps should come as little surprise; a young artist named Shigeru Miyamoto is credited by some for its graphic design, though his precise role is a matter of considerable debate. Some source cite him as a graphic designer, while others indicate he worked only on the cabinet art, and David Sheff's Game Over simply states that he found it "simplistic and banal" after the fact.

Whatever the case, Radar Scope did reasonably well in Japan following its December 1979 debut; according to Chris Kohler's Power•Up, only Pac-Man outperformed it throughout 1980. As the most popular of Nintendo's stable of early arcade projects, the company's management pegged it as the ideal candidate to serve as the vanguard of its move into international markets. Several thousand Radar Scope units were manufactured and shipped to New York City to be sold across America. Nintendo was about to go global in a big way.

Alas, it was not to be; instead, Nintendo's Radar Scope ambitions led to near-disaster. Nintendo didn't seem to realize that Space Invaders, while popular around the world, never saw the same success outside of Japan that it had in its home territory. While Invaders commanded such mindshare in Japan that simply making a similar game was a sure ticket to massive cashflow for several years, that wasn't the case elsewhere.

In any case, the logistics of international business proved daunting for a company as small as Nintendo. Rather than licensing the game to an American manufacturer as Namco and Konami did for titles like Pac-Man and Frogger, Nintendo aspired to build its own network by going it alone -- admirable, but also a huge risk. Radar Scope didn't enter the U.S. market until November 1980, almost a full year after its Japanese debut, by which late date the Invaders clone ship had sailed. Pac-Mania dominated the world, and a rigid missile base shooter felt hopelessly dated... even one with fancy graphical embellishments like those sported by Radar Scope.

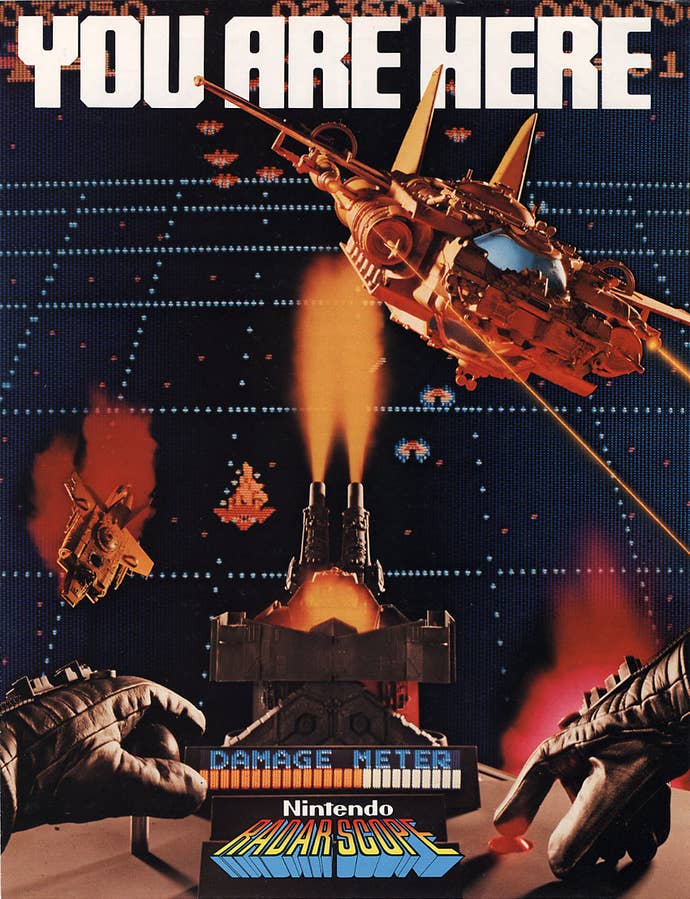

The net result was that Radar Scope -- Nintendo's entrée into the U.S. market -- nearly sank the company. Only a third of the units they hoped to ship across the country found buyers, leaving them not only with pricey unsold inventory but also footing the bill for the expensive warehouse space necessary to store a few thousand arcade cabinets. Of course, what happened next has become legend: Nintendo's boss, the late Hiroshi Yamauchi, tapped Miyamoto to come up with a new game that could be swapped into those unwanted Radar Scope cabinets. This led to Donkey Kong, which in turn led not only to arcade profits but also gave Nintendo a lever with which to enter the console market.

Sadly, Radar Scope tends to be brushed under the rug as a matter of no real significance: A failed game whose only positive contribution to gaming history was providing an opportunity for something better to come along. In truth, though, Radar Scope wasn't a poor game by any measure; its crimes were instead a simple matter of timing, and of being the focus of Nintendo's ill-conceived ambitions.

As Space Invaders knock-offs go, Radar Scope really was pretty solid. It borrowed liberally from both Space Invaders and Galaxian, the two big names in the arcades at the time, but it felt unique within the confines of the fixed-screen shooter genre. The pitched battlefield was more than a visual embellishment, as it helped create a sense of distance that limited the player's attack range. Most enemies hovered out of range until their active comrades were destroyed, at which point they'd come forward into the "live" field of combat. Not only did this affect the player's tactics, it also gave a sense of progression and accomplishment as the enemy's numbers slowly thinned away.

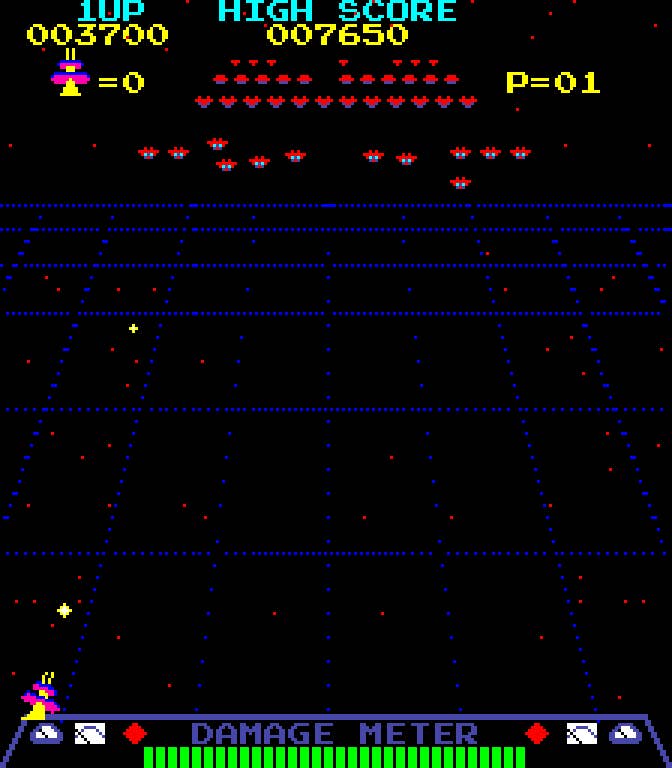

The enemy's patterns brought a new level of complexity to the genre as well. As opponents swooped forward to attack, they grew in size with a scaling effect. Destroying enemies at their largest, nearest point of attack would net a player more points, though there was also considerable danger to this tactic; attacking ships didn't simply shoot straight ahead as in other Space Invaders clones, but could also fire at a 45-degree angle as they swept along the lower edge of the screen. Additional game factors like the damage meter that displayed the health of the base the player had to protect and enemy ships that would flame out and come crashing to the bottom of the screen kept things lively.

It's a shame most people will probably never play Radar Scope legitimately; given its poor performance, it's something of a rarity these days. And Nintendo for its part resolutely ignores the existence of its pre-NES game catalog, so we'll almost certainly never see Radar Scope collected onto any sort of anthology or reproduced on Virtual Console. Still, the most important thing about Radar Scope definitely comes from the way it demonstrates Nintendo's history of misreading the market only to bounce back with a perfect saving throw. The only question now is whether or not history will repeat itself once again with Wii U.

Glass Joe Delivers Knockout Blow to Nintendo's Arcade Division

What a difference five years can make. Just half a decade after a brush with disaster precipitated by Radar Scope, Nintendo had established itself not only as the purveyor of a world-class arcade franchise (in Donkey Kong) but also as an up-and-coming successor to the console market vacuum left by the collapse of Atari and its competitors.

1984 saw Nintendo's Famicom make serious headway in the Japanese home market, quickly leaving behind rival platforms Sega SG-1000 and the MSX hybrid computer. In fact, the Famicom was doing so well and involved so few financial risks relative to the arcade market -- which was beginning to decline following the golden age of the early '80s -- that Nintendo was ready to pack it in and shift its focus entirely to consoles.

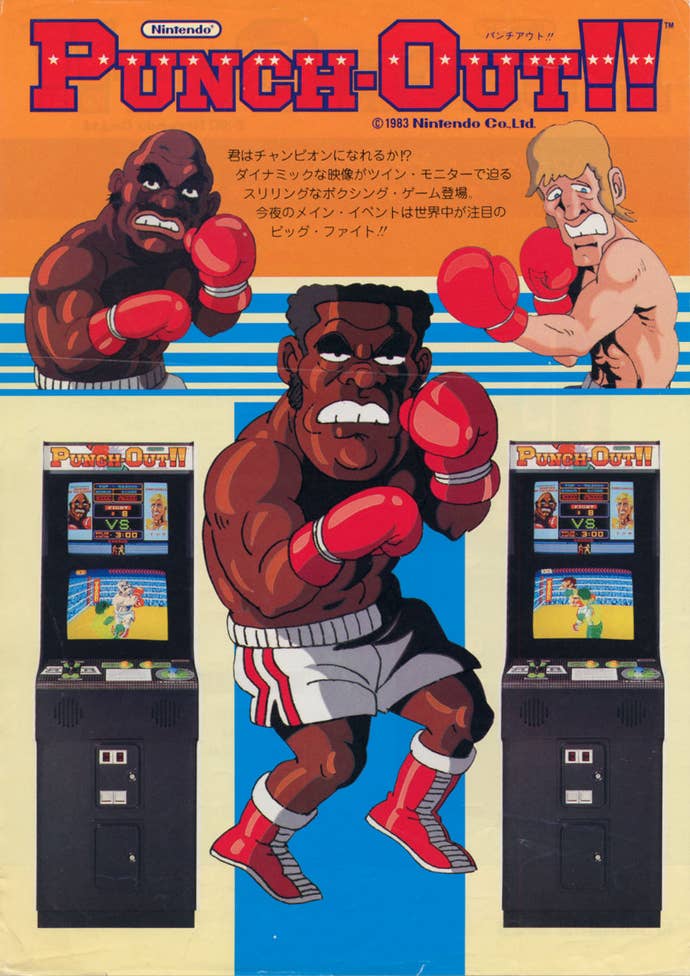

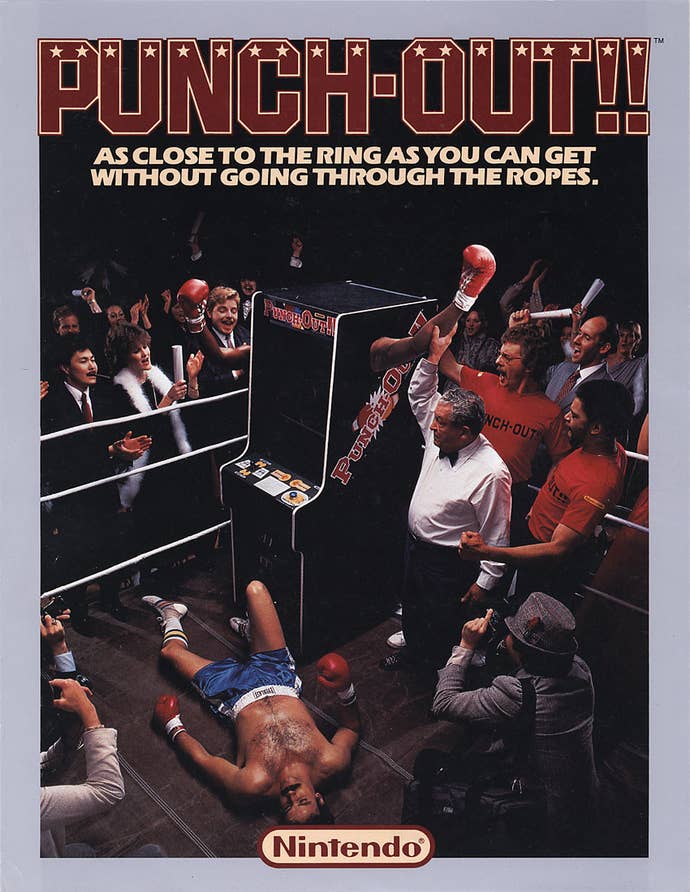

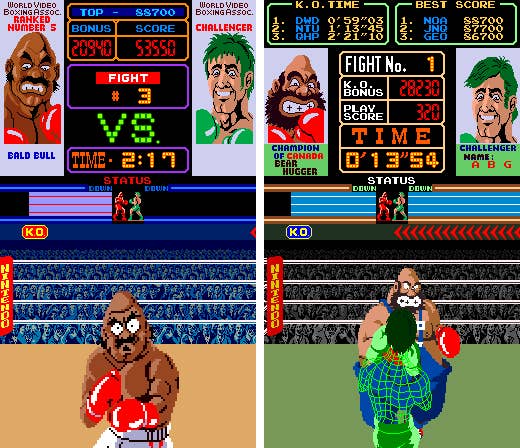

But that's OK, because before they reduced their coin-op presence to a series of pay-for-time NES demo kiosks, Nintendo delivered quite the coup de grace: A vibrant arcade boxing game called Punch-Out!!

Games had dabbled in boxing before Punch-Out!!, but nothing that had come before had come close to offering the level of presentation and action Nintendo piled into its take on the topic. By putting to use a scaling graphical effect -- something Sega would master in later years with its "Super Scaler" technology -- Nintendo was able to present its boxing with an over-the-shoulder perspective that shamed the competition. With its huge, cartoonish sprites, Punch-Out!! resembled a Laser Disc game, but it didn't rely on the cheat of streaming, pre-rendered video to wow players. Its graphics ran in real-time, meaning there were no awkward pauses or loading between actions. Just fast, fluid slugfests.

Some clever design work allowed the game to make use of its close-in perspective without the player's huge sprite getting in the way: During matches, the protagonist was rendered as a bright green grid, making him largely transparent in an age before alpha channels and transparency layers -- you could see right through your on-screen avatar to watch your opponent's moves.

Admittedly, those moves were considerably less intricate than in the more famous NES version of the game. The home conversion traded visual splendor for more refined game mechanics; the bad guys weren't nearly as large as in the arcade game, and the protagonist was reduced to a comical waist-high wimp, but the roster of opponents expanded considerably and their tells became far more interesting. In the arcade, you basically just watched for their eyes to flash and hoped for the best.

Make no mistake, though: Punch-Out!! was no mere prototype waiting for something better to come along. It was a perfect arcade sports game, fast-paced and visually striking. It sounded great, too, as a digitized announcer called out moves and encouraged you to climb to your feet when you failed. It's a similar experience overall to the NES game, even incorporating many of the same characters, but it's different enough to feel wholly unique.

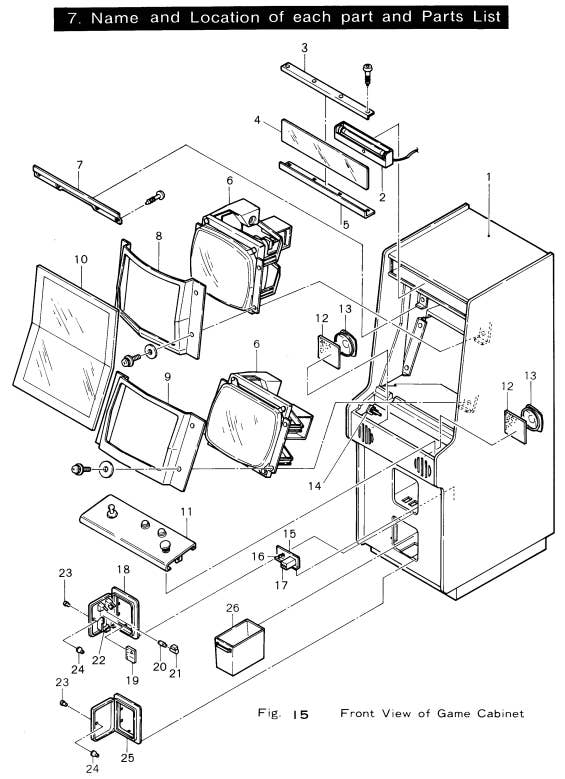

Of course, like so many classic Nintendo arcade games, it may as well have never existed for all that the company seems eager to brush it under the carpet. It's a pity, because its unusual cabinet structure -- with two screens stacked on top of one another, one dedicated to displaying fight stats -- would work quite nicely on the company's modern-day dual-screen handhelds. In any case, it was quite the coin-op finale -- or close enough, since Nintendo's final two original releases, Super Punch-Out!! and Arm Wrestling, were based on the hardware and tech of this game -- and let Nintendo exit the arcade on a high note. How often does that happen?

Nothing Says "Toy" More Effectively Than a Gun

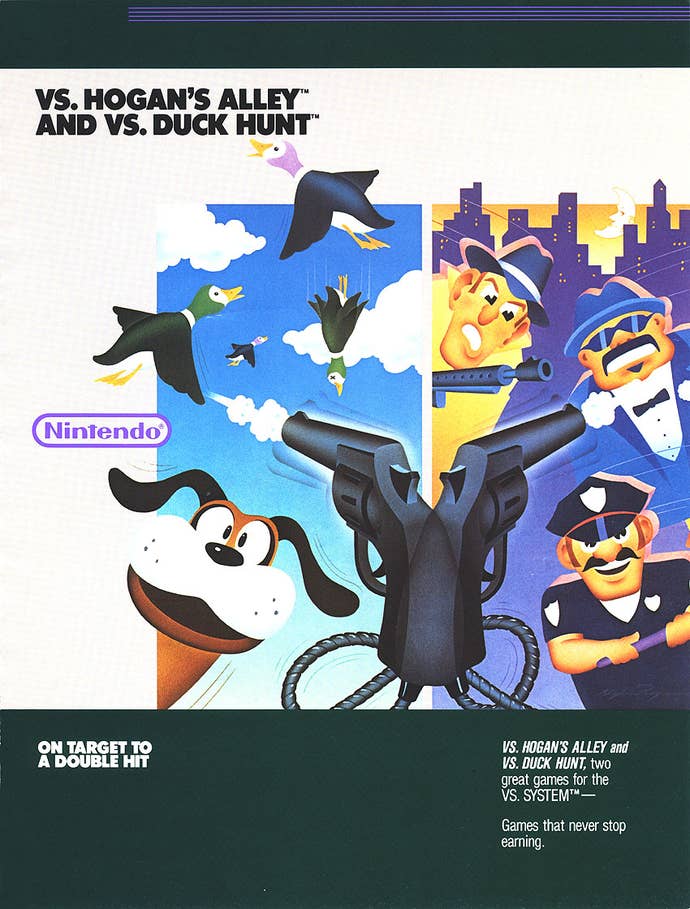

Back in the '80s, Nintendo quickly rose to the top once it entered the Japanese home market with Famicom. Yet they may never have been able to reproduce that success abroad if not for the presence of two famous peripherals: The Zapper light gun and R.O.B. the robot.

You should know the story by now: American retailers were burned out on games after taking huge losses in the wake of Atari's collapse, so Nintendo Trojan Horsed the NES into the market by presenting it as a toy, emphasizing its peripherals. The NES sold largely because of R.O.B.'s visual appeal and because Duck Hunt was deliriously fun.

Truth be told, it wasn't an entirely base deception. Sure, the games that made use of R.O.B. -- all two of them -- were pointless, and setting up the stupid robot in the first place was far more trouble than it was worth. But Duck Hunt, which shipped with NES bundles well into the system's stout middle age, was simple and addicting. Plus, it pretty much served as a perfect encapsulation of the Nintendo way of doing things. In fact, it effectively predicted how Nintendo would make its mark with the Wii more two decades later.

For starters, Duck Hunt was based on a vintage Nintendo game. This may sound strange -- as of 1984, the company had barely been in the video game business for half a decade -- but in fact the Duck Hunt brand predates Nintendo's video arcade business. Back in 1976, near the end of the company's run as a toy manufacturer, Nintendo created a standalone game called Duck Hunt, which projected images of ducks onto your wall and used a sensor in the gun barrel to register hits and misses.

Duck Hunt for NES takes this creative electronic devices and reinterprets it in video game form, in some cases almost literally: The video game's animation cycle (ducks fly at a roughly 45-degree angle and fall inverted to the ground upon being shot) is taken almost verbatim from the original. It's a remarkably faithful adaptation, in fact, but it's much more compact and convenient (not to mention colorful) in video game form. Much as the likes of Ultima made tabletop role-playing games much less cumbersome through digital automation, Duck Hunt for NES takes the whirring electromechanical noise out of the game and throws in little embellishments (some modest, like the backgrounds, and some memorable, like the sneering dog who mocks you for missing your targets).

Duck Hunt made a strong case for the NES as both toy and video game console, justifying the inclusion of a light gun with the system. Where R.O.B. was just a goofy waste of plastic, the Zapper -- paired with Duck Hunt -- made the NES memorable. For gamers who found the nuances of Super Mario Bros. too difficult to grasp, Duck Hunt's immediacy (you point and shoot at ducks with a gun, just like you would in real life) made it instantly relatable to everyone and helped the NES find acceptance that it might not otherwise have achieved with Mario alone.

Right here we see the formula Nintendo would use to conquer the world two decades later with Wii. The remote control-like stylings of the Wii's controller made it far more intuitive for general audiences than the competitions button-laden plastic bricks, and the simple, imitative design of Wii Sports offered a hook for grandma and grandpa to become hooked. And of course Nintendo would be nothing without its ability to dip into its back catalog and dredge up old concepts to refresh, just like they did back in 1984 with a clanky, decade-old electromechanical tabletop game. Some things never change.

Donkey Kong Country? More Like Donkey Cons Country

Ever since Mattel chose to sell the Intellivision platform by proclaiming its incredible graphical realism relative to Atari's 2600 -- our stick figures are better! -- technology has been the gaming business' preferred battleground.

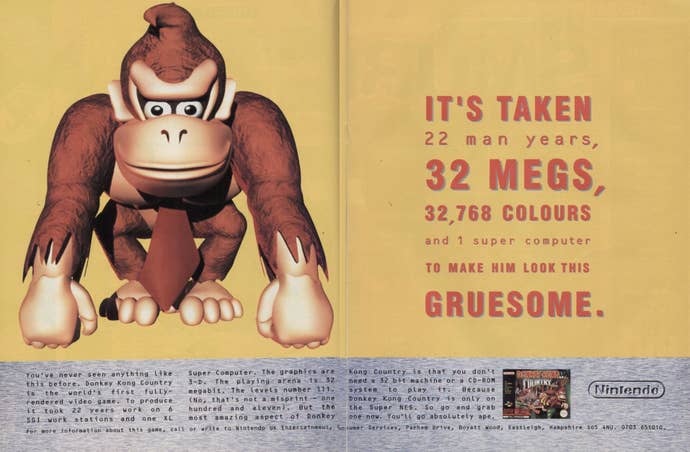

But technology marches ever onward, and while this year's system may trump the competition with its jaw-dropping power, next year it'll be nothing more than a dusty relic. So it went for Nintendo, whose Super NES offered the slickest graphics and most convincing audio of the 16-bit era... right up until the point at which it didn't. By 1994, a mere three years after the console's American debut, the Super NES had grown long in the tooth, and enthusiasm began to wane.

All throughout the 16-bit era, Nintendo had managed to fend off threats to the monopoly it built in the '80s with great software and some ruthless business decisions. Sega made headway with its Genesis, but even that juggernaut couldn't quite dethrone Nintendo as the industry's big player. The looming specter of Sony's PlayStation, however, painted a different picture. Its awe-inspiring 3D capabilities were a far cry from the clunky visuals produced by limp also-rans Atari Jaguar and 3DO, and even early glimpses of the likes of Ridge Racer absolutely shamed the meager polygons Nintendo's FX chip produced.

Unfortunately, Nintendo's own Super NES successor, the Ultra 64, was still a year away from prime time (actually, as it turned out, two years). All the company had to combat the promise of PlayStation and Sega Saturn was an aging console and increasingly expensive add-on chips that couldn't begin to measure up to what the competition had in store. So Nintendo, a company that got its start as a playing card manufacturer, did what any card player would do with a losing hand: It bluffed.

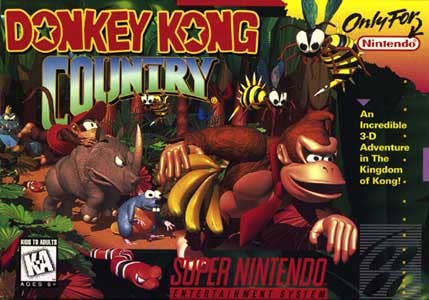

Nintendo's bluff came in the form of Donkey Kong Country, a total reimagining of the franchise that had catapulted the company to the big leagues in the first place. It was a game a long time coming; outside of that summer's largely overlooked remake of the original arcade title for Game Boy, Donkey Kong hadn't featured in a new game since Donkey Kong 3 a decade prior. In fact, besides the occasional cameo in unrelated works and the mysterious Return of Donkey Kong for NES (announced but never shown), the former arcade superstar had all but vanished. Kong's disappearance was quite an ignominious twist for a character who had once been one of the medium's most recognizable faces.

Perhaps Nintendo was simply holding him back for the right moment. Certainly DKC had profound impact. It brought back an '80s arcade staple in true '90s style: As the furry hero of a snarky platform action game. DKC was no mere Sonic clone, though. Not only did Kong have a valid claim on the genre despite his lengthy absence -- the original Donkey Kong being one of the format's seminal works -- the game was nothing short of astonishing from a visual perspective. Somehow, developer Rare managed to squeeze graphical fidelity from the wheezing Super NES that put the game's visuals on par with anything yet seen on more advanced hardware... and all without the use of one of those fancy add-on processors Nintendo was so fond of.

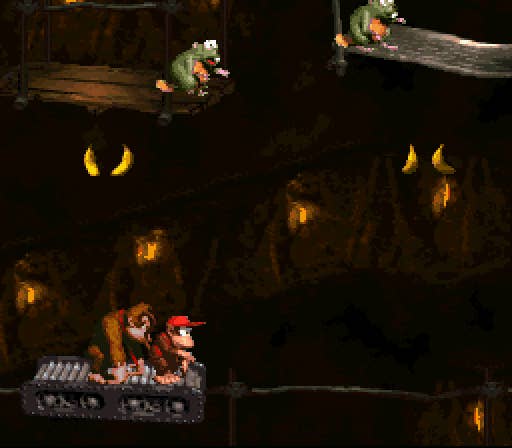

Of course, it was simply an illusion, a trick of clever graphical design. But what a trick! Rare fostered the perception that DKC was a game running on an advanced, 3D-capable system, despite the fact that under the hood DKC was arguably a step behind launch titles like Super Mario World and Super Castlevania IV. It eschewed the Super NES's built-in graphical modes, foregoing the platform's standard bag of gimmicks (rotation, transparencies, etc.) in favor of a game that impressed strictly with its basic visual design.

But that design really was impressive. Quibbles about the main character's radical '90s redesign aside, DKC banked on the public's general inexperience with 3D graphics to wow the masses with a game whose technological advancements happened entirely on the development side. There was nothing special under the hood of the DKC cart or the Super NES. Instead, Rare put cutting-edge computer techniques to use in the crafting of the game.

Never mind that DKC was, at heart, a fairly standard platformer. Kong and his sidekick Diddy could run and jump per usual, attack with an open-palmed ground slap, roll into foes like Sonic, and ride around on a variety of animal pals. There was really nothing about DKC that hadn't been done dozens of times before by dozens of other platformers, often in a much more fashion. But it didn't matter. DKC wasn't about revolutionizing the way games played; it was about convincing gamers not to trade in their Super Nintendo systems for something better. And it worked.

It worked because Nintendo and Rare's hunch was right. Most people didn't have real experience with true 3D game worlds in 1994, so DKC's fixed perspective didn't betray it as a relic of 16-bit hardware. When people thought of advanced computer graphics, they thought of the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park or the previews they'd seen of the upcoming Disney cartoon Toy Story. DKC looked much more like Buzz Lightyear than the boxy dominatrices of Toshinden did; in many ways, DKC's 3D fakery was better than actual 3D. Certainly it was more satisfying to look at.

DKC's design and legacy have left it open to considerable criticism over the years. The flimflammery of its visuals and the relative mundanity of its actual game design make it easy for critics to paint it as a classic case of style over substance. There's also the (seemingly apocryphal) claim that Donkey Kong creator Shigeru Miyamoto found DKC lackluster and amateurish, leading to the creation of the elaborately lo-fi Yoshi's Island as a reactionary piece.

But while those criticisms have some merit, they're not entirely fair, either. Sometimes, style is substance, and DKC is a masterful example of that axiom in action. This was no slapdash half-effort; Rare's designers didn't simply punch some numbers into a supercomputer and wait for the game to emerge fully formed from a slot on the side. On the contrary, DKC exudes craftsmanship. Rare went to great pains to create a consistent, seamless world that managed to convey trompe-l'oeil immersion despite being made of the same flat bitmap tiles that every other 2D platformer on the market used. This was no trivial matter, as countless games that attempted to borrow DKC's production techniques would prove: Few looked as clean or consistent as Rare's work, which committed to the illusion and pulled it off impeccably.

Before too long, actual 3D games would become commonplace, and "2.5D" platformers like Crystal Dynamics' Pandemonium! would expose the illusion upon which DKC was built. But in 1994, it didn't matter. Nintendo stood at the brink of obsolescence and made the biggest bluff in its century of existence. Incredibly, it worked. As Sony and Sega ushered in the 32-bit era, the creaky old Super NES enjoyed its strongest sales ever. Perhaps even more amazingly, people cared about Donkey Kong again for the first time in a decade. Not bad for a crazy handful of nothing.

Oh Snap! Pokémon to the rescue!

Nintendo built its '80s console empire on a foundation comprised of two elements: Great software and cunning business practices. The former made the company a lot of fans, and the latter made them a lot of money... but not a lot of allies.

By the time the Nintendo 64 console had reached its middle age, most of the third-party publishers that once graced the NES and Super NES with games both good and terrible had jumped ship in search of more fruitful ways to do business. Nintendo's strict licensing terms, self-centered publishing policies, and determination to stick with the cartridge format in the face of an industry-wide shift to CD media turned N64 into a ghost town even as a record number of games appeared on Sony's PlayStation.

The N64's carts may have been an artistically motivated choice -- Nintendo's designers supposedly wanted to avoid the lengthy loading times that affected CD-based games -- but they amounted to business suicide. They offered incredibly limited storage space compared to CDs; they raised the costs of development (simply porting Resident Evil 2 to N64 cost a million dollars in an era where top-tier games rarely cost more than $2-3 million); and they caused N64 games to retail for $20-40 more than comparable PS1 games. N64 was bad business for everyone, including Nintendo... and it came right on the heels of the disastrous Virtual Boy.

Yes, the late '90s were a dark time for Nintendo, which a mere decade before had clutched the whole of the console gaming industry in a vice-like grip. The N64 era could have been the end of the legacy that began with the NES if not for a massive lucky windfall: The wild, runaway success of Pokémon. An unassuming role-playing game that launched quietly in Japan in 1995 for the slowly fading Game Boy handheld, Pokémon snowballed into a juggernaut through word of mouth. By the time Nintendo and Game Freak had reworked the patchy Japanese original for international release, three years later, Pokémon was a brand consisting not only of a game but also of toys, cartoons, cards, and more -- all of which arrived in concert with the Western versions of the game. The simultaneous onslaught sparked an instant global hit, selling millions of games and untold amounts of merchandise. While Nintendo didn't exclusively own the Pokémon brand, they held enough of a stake to rake in a huge fortune from the franchise's international popularity. That windfall helped keep things in the black for the company even as its marketshare shrank. And it had a side benefit, too: The Game Boy, that aging and technologically primitive handheld, suddenly got a new lease on life.

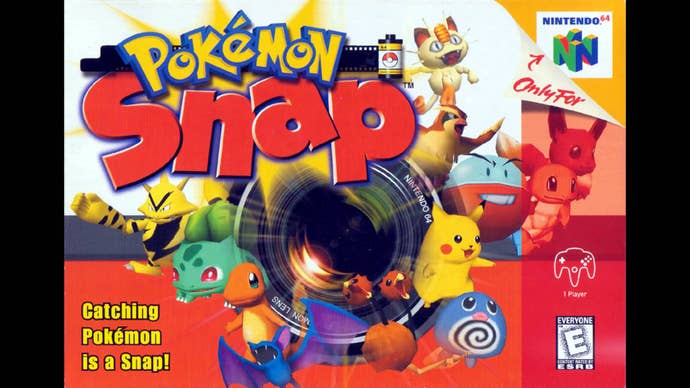

Nintendo was quick to take the Pokémon series beyond the limited bounds of the Game Boy. While the core games have remained handheld-based to this day, the character-driven nature of the franchise lent itself to any number of interpretations. On one hand, you had something like Pokémon Battle Stadium, which reduced the RPG concept down to a series of arena-based battles. On the another, you had the far more intriguing Pokémon Snap.

Pokémon fans have clamored for the core RPGs to come to consoles for as long as the franchise has been around -- some feel the series is too good to languish in the "handheld ghetto." Snap disappointed those players by very decidedly not reproducing the RPG design of Pokémon Red and Blue on N64. It's a very different kind of game -- and, truth be told, a far more memorable one than a mere graphical overhaul of a Game Boy adventure would have been.

The idea behind Pokémon Snap wasn't really to go on a grand adventure in the world of Pokémon. Instead, it focused on the creatures themselves in a highly restrictive format that nevertheless demanded high-level play. Game Freak had created 151 unique monsters for their game, but in practice they amounted to little more than a collection of statistics for combat with the occasional in-world cameo for the sake of window dressing. Snap turned the focus entirely away from fighting, giving fans a glimpse of how pokémon behaved in the wild and how those wild combat powers translated into more mundane situations.

Snap's appeal came from the same place as that of the pokémon anime: It took the games, whose universe and characters were depicted with monochromatic minimalism, and rendered those concepts in more elaborate detail. Unlike the cartoon, however, Snap wasn't shackled to the misadventures of a dopey kid and his pet rat. Instead, it allowed players to enter the world of Pokémon for themselves and see the creatures interacting on their own: A virtual safari full of fantastic beasts.

Just as Pokémon Red and Blue could only really work on Game Boy -- this was around the time NCL President Hiroshi Yamauchi excoriated RPGs for appealing to shut-ins, putting his money where his mouth was by offering an RPG that actively fostered socialization through Game Boy's portability and connectivity -- so too could Snap only have worked on N64. The cramped confines of a cartridge wouldn't have been sufficient to contain games as expansive as the Pokémon RPGs in proper 64-bit 3D, but they had more than enough room for a simple on-rails safari adventure -- albeit one that didn't include even half the total pokémon species from the franchise's first generation.

Truth be told, Snap was basically little more than a rail shooter. The difference was that rather than shooting pokémon with guns, players shot them with cameras. This created a different form of challenge than the typical kill-or-be-killed take on the genre, encouraging players not to dominate enemies but rather to excel artistically. Given only a few film roll's worth of shots, how could you best frame each one? Timing, focus, and zoom mattered, and players were scored at the end of each journey to grade their talents as a camera master.

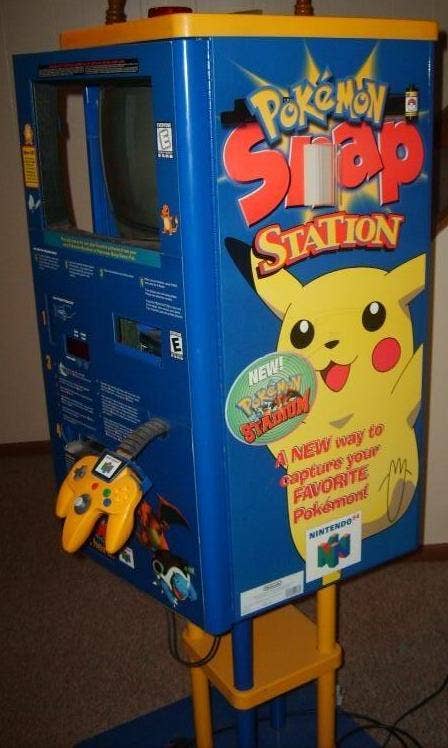

Snap even took on a life of its own through the Pokémon Snap Station, a location-based kiosk service that allowed fans to load up their Snap saves and create stickers from them. For a Pokémon-obsessed kid, it was the equivalent of taking their vacation pictures to the one-hour photomat.

The strangest thing about Pokémon Snap is that there's never really been a proper follow-up despite its popularity. One might think the 3DS, with its gyroscopic motion sensor and AR features, would offer a perfect home for a Pokémon Snap 2. With 10 times as many creatures available in the current generation as were present in the original Snap, there's certainly no shortage of opportunities for original photo scenarios. But as a historical artifact, Snap embodies Nintendo's savvy: Shoring up a weakness in one area by capitalizing on a popular brand in an unexpected but entertaining way.