Five Critical, Historic FPS Milestones Every Gamer Should Know

Which game was the first true FPS? Which FPS went retro before we even knew what retro was? Which FPS is the real thinking-man's shooter? Jeremy looks at five key moments in the evolution of the genre.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

We've all seen and played many, many first-person shooters over the years, but do you know their history? Their roots? Their genetic fundamentals? If you're shaking your head, you really need to read on. And if you are. Well, we'd like to see how your knowledge stacks up against our feast of tasty historical informational nugs.

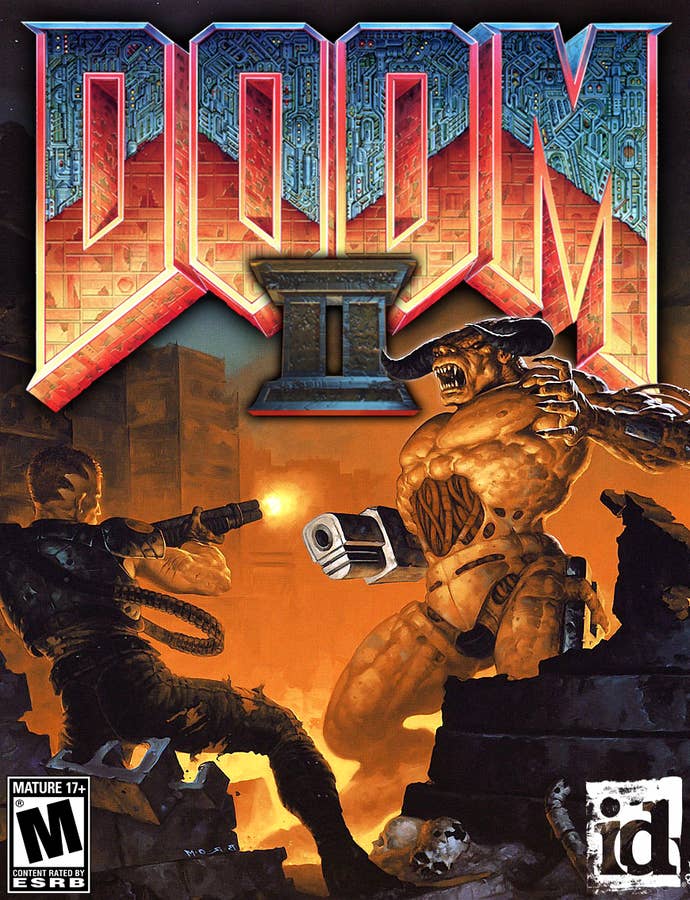

Doom II Proves the Value of More of the Same

What matters more? Advancement through innovation or improvement through iteration? This may well be the single most important – not to mention difficult – question when it comes to canonizing the history of video games.

Consider Doom and Doom II. The first game practically invented the first-person shooter; yes, other developers had created games in which players moved about in a first-person perspective and shot things, but never had it felt so intense. So huge. So fast. There's a reason, after all, that for its first few years the FPS genre didn't have an official designation. We just called them "Doom clones."

And then there was Doom II, which did very little to add to its predecessor's framework. The graphics weren't noticeably improved, you didn't see much in the way of new weapons. There were only a handful of new monsters, and even the environments generally looked about the same as previous game despite largely taking place on Earth rather than Mars. What Doom II did accomplish, however, was to explore the original Doom's fundamental concepts in more sophisticated ways.

Level designs retained the first game's free-form structure while presenting layouts that were at once more intricate yet less confusing than what had come before. Despite their general familiarity, Doom II's monsters appeared in more dangerous and challenging situations – up to and including its treatment of Doom's bosses as standard encounters – while at the same time their placement allowed for more potential interactions with one another rather than with the player alone. Smart space marines could stir up interspecies conflicts to trick their foes into thinning their own ranks before wading into the fray themselves. And finally, the first game's episodic structure gave way to a single continuous story; while the action still broke down into standalone levels, there were no chapter breaks resetting the gear you'd collected, building a greater sense of progress and consistency throughout the adventure.

Most importantly, though, Doom II greatly improved the multiplayer experience. The original Doom, distributed in an age of dial-up modems, was never meant to support online play, only local-area network multiplayer. Such was the game's popularity – not to mention its extensibility and appeal to computer-savvy types who regarded technical limitations not as absolutes but rather as puzzles to be cracked – that within a matter of months Doom fans had come up with a number of clever workarounds to let them go head-to-head via modem, including at least one short-lived business which existed expressly for that purpose. Many of Doom II's improvements involved its multiplayer tech, supporting not only LAN play but also services like DWANGO and direct peer-to-peer connections.

Yet while it improved on every single one of Doom's concepts, Doom II is generally treated as something of an afterthought when considering the series' legacy – the "oh yes, and also" footnote to all that the original game accomplished. After all, Doom didn't only cement the first-person shooter as a key pillar of the games industry (20 years later, most of the biggest and most widely played games worldwide descend directly from Doom). No, it also revolutionized game distribution, with a free four-level demo that players could download or pick up on free (or at least cheap) diskette samplers before purchasing the rest of the game.

Because it was so revolutionary and so widely accessible, Doom crowds the collective conscious of gamers who were, say, ages 13-25 in 1993 – the same ones (such as me) most likely to chronicle the history of the medium for the moment. The guttural moans of demons emerging from the darkness and mingling with the fast-paced MIDI jam "E1M1" has the same resonance for many gamers as the opening jingle of Super Mario Bros. or the staccato pulse of Call of Duty's rifles for games who cut their teeth in different decades But between Doom and Doom II, was the original the better game? Or was it simply the more important one?

In truth, it's a moot question. Neither game truly works without the other. We needed Doom to get the whole thing started, but Doom II demonstrated the potential of Doom's concepts. It revealed the value of refinement – a task every bit as essential as raw invention. Innovation and iteration go hand-in-hand as the motive forces of game design, and the original Doom duology offers a perfect glimpse of the very different faces of progress in action. If Doom invented the FPS, Doom II perfected it.

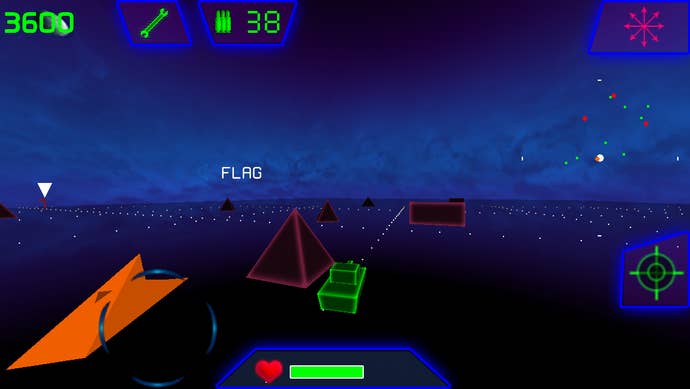

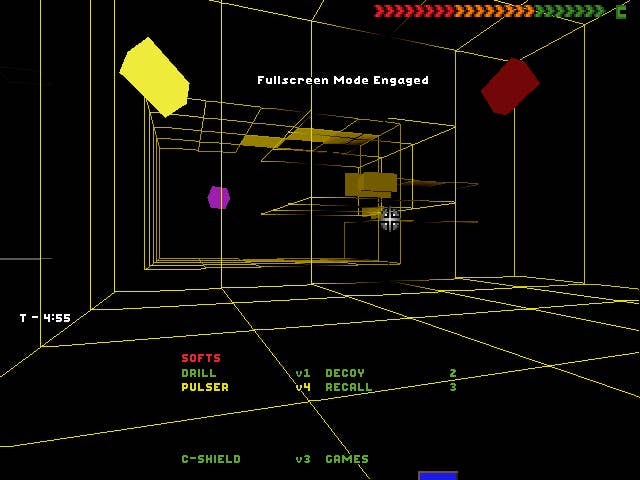

Spectre VR goes Old-School when Old-School was still New-School

While iD Software was perfecting Doom II in 1994, at the same time a studio called Peninsula Gameworks produced an FPS PC that felt like a relic from another time - yet still remains important.

The reality was that Spectre VR – the second sequel to 1990's Mac classic Spectre – actually did belong to another time. Doom, its sequel, and its imitators approached the task of combat viewed from a first-person, three-dimensional perspective by going the visceral route. Players climbed into the head of a lone warrior, getting in close and reducing enemies to piles of gore, literally getting blood on their hands... or at least their avatar's hands, that is. Spectre's approach hearkened back to the classic arcade. All the way back to 1980, in fact, and Atari's Battlezone.

To be precise, Spectre VR's creators very deliberately patterned their shooter after Battlezone. The game's first-person perspective dropped players into the cockpit of a sleek futuristic tank. The graphics rendered the world and everything in it as a conscious imitation of Battlezone's vector-based graphics, with simple, colorful polygons and razor-sharp lines glowing against a field of black. It even imitated the distinctive typefaces of other Atari vector titles like Tempest. Spectre VR was retro before anyone knew what a "retro game" even was.

Despite its fundamental similarity to Doom, the two games felt nothing alike. Spectre VR was all crisp polygons and neon glow set in vast, open arenas – the polar opposite of Doom's dank, claustrophobic military bases. Enemies consisted of triangles that exploded into smaller triangles upon being shot, not demonic abominations that fell to bloody pieces. Spectre's mission objectives amounted to little more than capturing flags in an arena. It was the product of a simpler time, updated to take advantage of the Macintosh's graphical horsepower.

Spectre VR had another advantage over its arcade inspiration besides mere graphical horsepower: Networking. Battlezone, by simple virtue of being an arcade game from 1980, could only offer solo play. It wasn't even the kind of game others could crowd around to watch, since Atari's Ed Rotberg designed it to be experienced through a viewfinder. Spectre VR, on the other hand, could use Apple's speedy (albeit fussy) AppleTalk networking protocol to allow LAN play for several people at once. In fact, this was the main feature Spectre VR offered over its otherwise-similar predecessor, Spectre Supreme.

Spectre VR hasn't aged nearly as well as Doom, to be honest. If its simplistic play and relatively slow pace felt dated in 1994, they come across as downright archaic now. Even so, it had a place in its time – a valuable demonstration that shooters didn't need to present themselves as bloody heavy metal album covers designed to make your mom angry in order to be fun. Besides, in an age where so many developers look back to the early '80s for aesthetic and mechanical inspiration, Spectre VR's backward glances made it curiously ahead of its time, too.

System Shock: a Study in Parallel Evolution

When id unleashed Doom upon the world through that poor, overburdened FTP late in 1993, one of gaming's most popular video game genres truly came into its own.

But it's important to remember that, influential as it was, Doom was by no means the world's first FPS. Bethesda created a 3D, first-person, open-world action game based on the Terminator back in 1990. Few early first-person games, however, offered the depth and quality of content as Origin Systems' Ultima Underworld.

In a way, Ultima Underworld represented a back-to-the-roots take on the Ultima games, which in their earliest days featured first-person dungeon exploration through simple 3D wireframe graphics. Underworld, however, featured top-of-the-line visuals upon its debut in 1992, and it abandoned Ultima's traditional combat system to maintain a consistent sort of immersion; players battled monsters in real time from the same point of view through which they explored the underworld. Its unique combination of first-person action, role-playing depth, and high fantasy aesthetics had a tremendous influence on the likes of Elder Scrolls: Arena and even the id-published own Heretic.

And then there was System Shock. Though not a direct sequel to the Ultima Underworld games, System Shock is arguably that series' truest successor. Created by key Underworld personnel (including producer Warren Spector and programmer Doug Church), System Shock recast the fundamental play style of Underworld in a science fiction setting. With the transition away from dreary fantasy into austere future, the action changed in turn as well, becoming slightly faster. Still, System Shock didn't abandon its RPG roots; it retained concepts like inventory, character upgrades, and most of all a heavy emphasis on narrative. Different weapons worked more effectively against specific enemies. And many upgrades and recovery items carried detrimental side effects, forcing players to balance their desire for raw power with the need to avoid stacking up too many disadvantages.

What the change in setting did bring, however, was the freedom to explore new concepts. No longer beholden to goblin-packed caverns, System Shock developers Looking Glass Studios crafted a sophisticated story heavily inspired by William Gibson's Neuromancer; players controlled an anonymous hacker thrust into conflict with an unhinged A.I., and the cat-and-mouse relationship between the hacker and the SHODAN machine intelligence that unfolded throughout the adventure provided the plot that drove the action. Like Neuromancer's Case, the player's hacker possessed a number of neural implants grafted to his body; these not only provided the opportunity to improve and customize the protagonist's skills without resorting to a standard RPG leveling system, they also gave him access to a separate mode called Cyberspace... which, again, came straight from Neuromancer.

With all of these features combined into a single creation, System Shock straddled the line between shooter, RPG, and graphical adventure. Besides Ultima Underworld, its closest antecedent was Bungie's 1993 first-person adventure Pathways Into Darkness, which featured a similar style of play (including "levels" that could be revisited in a free-form world) and also revealed its story through passive text dumps at key locations rather than interaction with living beings. Much like its spiritual descendent BioShock, System Shock saw the protagonist completely isolated from other living creatures (except, of course, the ones that wanted to kill him). The plot unfolded through notes left about the space station and computer terminals where SHODAN would rant at you, and any creatures you encountered in the course of the adventure had the singular goal of destroying you.

This delicate balance of genre influences was all well and good, but what really brought the whole of System Shock together were its top-notch production values. Its true 3D world allowed for greater immersion than Doom's fake-perspective engine; players could look in all directions without the visuals distorting or breaking apart, whereas competing game engines at the time were forced to limit vertical head tracking in order to preserve their illusion of 3D. The dynamic music changed according to the player's current situation, allowing for seamless shifts in mood amidst free exploration of the space station.

Doom may have had the wider influence, but System Shock commands an impressive legacy in its own right. Its creators went on to design similarly dense and thoughtful shooters such as Deus Ex and BioShock, and its core customization mechanics have become integral components of the FPS genre – even in games that actively try to be as un-game-like as possible, such as Call of Duty. It represents a different branch of game design evolution, one that's crossbred into the lineage of pure action shooters, but whose legacy remains distinct.

Descent, the Most Literal Interpretation of "3D Shooter"

If anyone tells you that Quake was the first truly 3D first-person shooter (by which they mean "totally made out of polygons"), just smile to yourself and remember Descent. After all, it's just video game trivia, and it's not worth getting into an argument about it. Or is it? If you're ever in the mood to put someone straight, the following information will be useful to you.

Of course, I suppose it all boils down to how you choose to define "first-person shooter." Descent is a game in which you play from a first-person perspective and shoot things... but despite being based entirely in narrow corridors and allowing unconvention side-to-side movement, it does have more in common with a flight combat game (e.g. Lawrence Holland's X-Wing series) than with Doom. That is to say, your avatar isn't anchored by gravity, mainly. But on the other hand, the action revolves around small skirmishes in tight passageways and larger self-contained spaces, like your classic FPS. So which is it?

The answer, obviously, is "Who cares?" Descent stood astride two young genres, harnessing their concepts to create a unique mix. And when I say unique, I mean it – though Descent saw a number of sequels, after a while it mutated into the FreeSpace series, which featured 3D flight but abandoned the intricate tunnels that kept Descent from being a pure flight and combat simulator. Two decades later, you really won't find anything else quite like Descent out there.

The secret ingredient behind Descent's distinct style? It took the term "3D shooter" very literally. Not only did it present players with entirely polygonal environments in an age when everyone else was faking it by extruding chunks of flat surfaces into a facsimile of three-dimensionality, it went the extra step by completely abandoning all sense of up and down. Do you love the horizon? A sense of knowing the difference between up and down? The ability to orientate yourself with ease? Descent wants nothing to do with your terrestrial limitations.

Set in a series of extraplanetary mining tunnels, Descent dispensed with gravity to send players into labyrinthine tunnels that sprawled in every direction. Every direction. Not just the eight points of the compass, but in 360 degrees on every axis. Passageways would wind from one junction to another by twisting in any direction, sometimes doubling back on themselves. No matter how determined you may have been to set a given direction as "up," the complex level designs would quickly force you to abandon your intentions. Like a space flight sim, every direction was a valid axis of movement; unlike those other games, however, getting from point A to B frequently required navigating some of the most twisted virtual spaces ever devised.

In truth, Descent's movement wasn't truly free-form. Your actions were restricted to six axes – but given that this was four more than other shooters of the time allowed (remember, Doom didn't even let you manually aim up or down), that was more than enough to feel utterly dizzying. Thankfully, Descent was a much slower and more deliberate game than, say, Doom. The designers accounted for the fact that moving through the game world would probably leave you disoriented and possibly even dizzy, so most of the hazards that populated Descent's passages were fairly passive, giving you sufficient time to get your bearings and draw a bead on them. Descent was the sort of game that flight sticks were invented for. The multiplayer mode, however, offered no such grace – if you happened to go up against an opponent who took naturally to the game's discombobulating style, well, good luck.

You can certainly understand why Descent eventually faded and FreeSpace rose to take its place; its unconventional mechanics place a lot of demands on players. Running around on a 3D world consisting of flat surfaces can be taxing enough for many people; playing an even greater burden of virtual navigation and visual orienteering on them is asking quite a lot. Thankfully, Descent has remained in publication these many years and can easily be played on modern systems thanks to its ready availability through services like Steam and Desura. There are even more ambitious fanworks available as well, such as DXX-Rebirth. So check it out and consider yourself in the know next time someone opines about the history of 3D shooters. Just try not to look too smug about it.

Marathon, The Other Thinking Man's Shooter

They say that if you were to give an infinite number of monkeys and infinite number of typewriters, eventually they'd bang out the collected works of Shakespeare. But when it came to early first-person shooter developers, that sort of coincidence happened with much less effort.

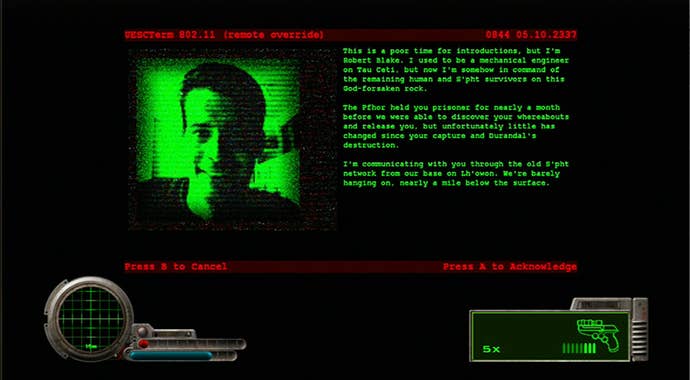

Despite being released only a couple of months after System Shock, Bungie's Marathon turned out to be a weirdly similar take on the FPS in many respects. Both games saw players take the role of a sci-adventurer trapped on an isolated spacebound location, go up against a rogue artificial intelligence, and unlock an extensive plot indirectly through text relayed via computer terminals. The narrative and mechanical connections between the two would suggest some liberal borrowing on Bungie's behalf if not for the fact that the games came out in such rapid succession. It's just one of those things, apparently.

For Bungie, Marathon represented a variant on their previous creation, Pathways Into Darkness. Where that game had been, essentially, a graphical adventure (a la Myst or The Journeyman Project) that played out with the mechanics of an FPS, Marathon was an FPS that happened to feature elements of a graphical adventure. Its inventory system was far simpler than either Pathways in Darkness' or System Shock's, and there were no character upgrades to speak of; on the other hand, when it came to twitch shooting and manic combat, Marathon won hands down.

Marathon played a lot like Doom for the most part, but it featured more varied objectives. Admittedly, these usually amounted to "flip a switch somewhere" or "blow this thing up" or "reach the exit," but the involved narrative provided a great deal of window dressing for even the most mundane chores. Marathon went to great pains to explain why you were running around shooting things, why certain security drones would help you while others would open fire on you, what you were supposed to be doing when you were beamed over to the aliens' vessel, and what that giant cyborg in the weird throne room was all about.

Meanwhile, you as the lone space marine (technically, a security office) found yourself caught in a three-way war between a group of AIs designed to help run the day-to-day operations of the colony vessel Marathon and who all had their own ambitions. Loyal Leela tried to help from start to finish, constrained by the original parameters of her programming. Meanwhile, Durandal went rogue early and spent most of the middle game taunting you as he overrode Leela's lock on you to force you to do his bidding. And finally, Tycho appeared to have been taken offline during the alien attack that preceded the action, only to appear later on as the aliens' pet AI, whose grudge against Durandal and humanity was practically weaponized. The plot twisted and turned as you read both messages from the various AIs as well as other supplemental documents in Marathon's systems, and while you could certainly just bumble your way through the action without bothering to soak up the story, all that narrative made a great shooter even better.

Despite its talkiness, Marathon didn't slouch in the action department. It featured top-notch combat design, with dual functions for most weapons (a grenade launcher on the assault rifle, a charge shot for the plasma pistol, etc.) and a respectable array of enemy warriors to use those guns against. Level designs tended to be fairly intricate, with a number of navigational puzzles in place of Doom's annoying hidden doors. Although some of the aesthetic choices could be puzzling – this was a colony ship, so what was up with the open pools of molten magma? – the various locations you fought through each had their own unique feel. The Marathon herself was vast and intricate, while the alien vessel featured weird pulsating geometry and a decided lack of player-friendly features (recharge stations, computer terminals). And the brief excursion to a remote human colony was particularly memorable, forcing players to navigate an incredibly complex installation while racing against time and oxygen drain in the exterior vacuum of space.

And, like System Shock, Marathon ended up becoming a cult classic – though a different sort than Looking Glass' game. Bungie's project is most beloved among the tenacious types who embraced the idiocy of being Mac users during Apple's most inept era, as Marathon was one of the few top-flight action games designed exclusively for the platform at the time. At a time when Mac gamers were lucky to get half-hearted ports a year or two after a DOS release, Marathon's exclusivity was like sweet ambrosia. And clearly the game means a lot to Bungie, too, since Halo turned out to be Marathon reinvented as a cinematic action game, and Destiny appears cut from much of the same cloth as well.

Like most early shooters, Marathon is readily available for rediscovery thanks to modern rebuilds of its open-source code. Sure, it shows its age in a lot of ways... but at the same time it's kind of nice to go back and revisit the '90s, when you could get lost in an FPS like Marathon, Doom, or Descent. There's more to gaming than marching down a succession of cinematic shooting gallery hallways, after all.