13 years later, Final Fantasy 13 still tells one of the series’ most ambitious stories

The worst Final Fantasy? It’s not as crystal clear as it seems.

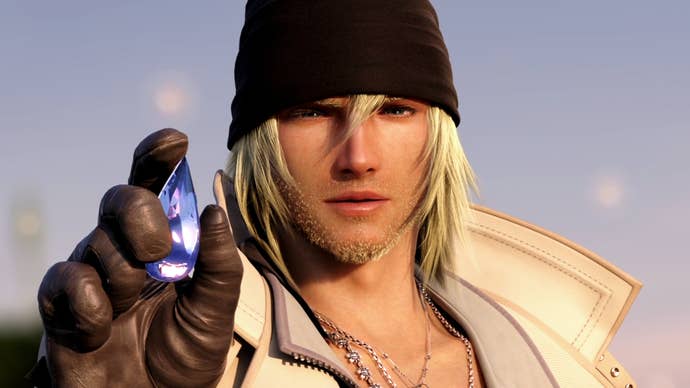

Final Fantasy 13 launched worldwide 13 years ago, and, since then, it’s developed a bit of a dodgy reputation. Environments that amounted to little more than bland hallways, a convoluted plot with a penchant for proper nouns, yet more changes to the battle system, and a dudebro hero whose heart of gold can’t mask his innate annoyingness came to define this awkward entry in the storied series. However valid some of these criticisms might be, they overshadow one of the more complex and important stories in the series, and perhaps even the genre as a whole.

Final Fantasy 13 is the series at its most daring. It isn’t about an evil government or even a power-hungry deity intent on shaping the world in his image. Lighting’s first adventure is something much darker and more insidious – something no other Final Fantasy or RPG has tried to tackle. It’s a case study in how easy it is for those in power to paint one group as “the other” and build a society based on prejudice and what it takes to make things right again.

Underneath the twisty plot and baffling names, Final Fantasy 13 is a story of social conflict and authoritarian regimes that leans heavily on motifs from Final Fantasy 7 (perhaps unsurprising considering the main scenario writer, Kazushige Nojima, also wrote Final Fantasy 7). The world of FF13 has two societies: Cocoon, a floating nation cut off from Gran Pulse, the world below. Fal’Cie are minor god-like deities whose essence power the world, and they shape and direct human life. Some humans come into contact with fa’Cie and get a Focus – a mission from the fal’Cie they must accomplish. These humans are known as l’Cie, and the ruling powers of Cocoon have convinced people that Pulse and their l’Cie are forces of evil intent on overthrowing social order.

The opening setup owes much to FF7.. A train hurtles along the railines of a high-tech industrial city, bathed in a green glow and with rather too many surveillance and military apparatus nearby for comfort. The passengers get antsy after passing a specific point, and our hero – an ex-military type – leaps into action with their sidekick, a concerned parent who fights to protect their child.

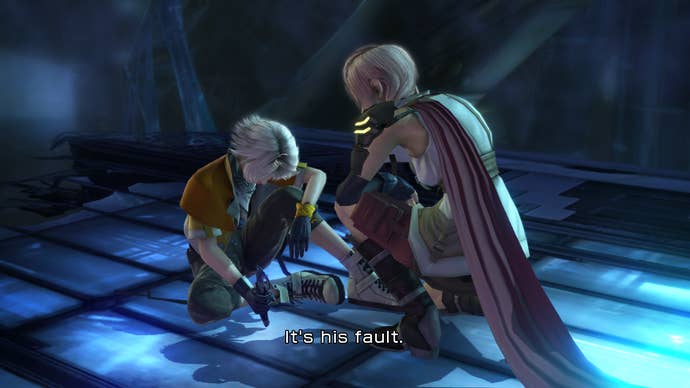

The point where things start to diverge is Lightning’s attitude. Cloud and the rest of Avalanche feel horrified when they realize their actions hurt others in Midgar, both in the slums and on the plate. Lightning feels no remorse for the destruction and probably death she causes, and for good reason.

I suspect someone on the narrative team must have read Ursula K. LeGuin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” between Final Fantasy 7 and Final Fantasy 13. The people of Midgar are passive. They may hate Shinra as much as the next slum dweller, but they’re stuck in the city, stuck without hope, stuck with the people who lured and trapped them there.

Everyone in Cocoon, however, is guilty. In LeGuin’s work, Omelas is a paradise, a city of happiness and prosperity built on one dirty secret. A child must be kept in darkness, squalor, and misery for their entire life so the city will continue to prosper. People learn of this injustice when they come of age. Most choose to live with it, letting “the other” suffer so they can be happy, though some find it so repugnant that they leave paradise behind.

Cocoon is a paradise as well. That’s what the ruling fal’Cie tell everyone, at least, and with a range of entertainment and pleasure options at their disposal, no one feels inclined to question them. The condition their happiness hinges on? Shipping a certain minority, l’Cie “contaminated” from the other world, off to die in routine purges. The Sanctum, Cocoon’s government, does its best to convince everyone the l’Cie are inhuman, a dire threat to order and everything good. It’s easier to believe a convenient lie and do nothing, so the people of Cocoon stand by and watch their neighbors die.

Passivity is a political action on Cocoon, one with fatal consequences.

Even Lightning and her cohort cooperate without question, like Final Fantasy versions of characters in Shirley Jackson’s classic short story, The Lottery. Jackson’s story takes place in a small, mid-century American town, a rural idyll with – you guessed it – a dark secret. Every year, the townsfolk hold The Lottery ritual to help ensure their prosperity for the next 12 months: they draw slips of paper at random, and the winning families and individuals get stoned to death. No one questions the custom – until it affects them.

It’s too late for Jackson’s doomed heroine to fight back, but when the purges touch Lightning and a handful of others – themselves not even branded as l’Cie yet – they don’t just leave Cocoon like LeGuin’s noble heroes or wail at their misfortune as Jackson’s characters do. They fight.

The problem is that Cocoon’s deep-seated rottenness means even standing up for yourself leads to more heartache.

After the opening segment where Lightning tries freeing those marked for purge, Final Fantasy 13 takes a break from the socio-political plot for a short while to focus on character drama, but it picks up strands of Final Fantasy 7’s narrative again about halfway through. Just as Cloud and co. discover Sephiroth is the real driving force behind Shinra, Lighting and friends learn that a devious fal’Cie is actually the mastermind behind the Sanctum, the purges, and essentially everything wrong with Cocoon.

Sephiroth wants to destroy the world in a bid to summon his extraterrestrial mother. Barthandelus wants to destroy Cocoon and use the mass death of its population to summon The Maker back. The Maker is the fal’Cie’s god, but even in Final Fantasy 13’s lore, the fal’Cie have no firm idea of why they want The Maker back aside from some poorly shaped idea of returning to a vague golden age – at the cost of practically every human life.

While Sephiroth’s attempt at summoning Meteor takes center stage in Final Fantasy 7, the fal’Cie’s goal in FF13 is less important than the means they use to achieve it. When Lightning and her fellow Pulse l’Cie fight back at the start of the game, it gives Barthandelus and The Sanctum an excuse to turn Cocoon’s passivity into violent hatred against those miscreants they believe pose a threat to their imagined heaven. Barthandelus even pulls off a clever political coup that paints the Cavalry, the only group in Cocoon with an inkling that The Sanctum is a problem as a power-grubbing group of terrorists.

The solution to Cocoon’s problem is, ostensibly, defeating Barthandelus and the tool he planned to summon The Maker with – the usual Final Fantasy solution, in other words. However, where defeating Kefka returned the world to normal in Final Fantasy 6, and shutting Sephiroth down saved the planet in FF7, killing the gods of Final Fantasy 13 could only ever be half of the solution. The infrastructure of fear and hate that the fal’Cie thrived on would remain even after their downfall.

For Lightning and the other l’Cie, killing their gods means unraveling society, and they take the responsibility on themselves to find a new way forward in the ruin. They dedicate themselves to promoting knowledge and education, so people can free themselves from the wilful ignorance they lived under during Sanctum rule.

For all of Final Fantasy 13’s dark portrayal of human society in its worst forms, it ends on a note of cautious optimism with the belief that people can change – if only someone is there to stand up to corrupt power and reshape the world. A pertinent message that's as relevant today as it was back in 2009.