Expat Game Dev Story: Inside Japan's Foreign Game Development Community

There are more western developers than ever in Japan, and they're doing everything they can to help Japan's indie community succeed overseas.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Nayan Ramachandran is living the dream. As the senior marketing manager at Playism, an Osaka-based startup engaged in everything from localization to software testing, he gets to live in Japan and work in the industry he loves - his dream job coming out of college. He's won the proverbial nerd lottery.

"When I was in college, I absolutely loved games, anime, and manga," he remembers. "I was thinking, 'I would love to live in Japan one day.' For a long time I couldn't figure out how to do that. I found out I could teach if I wanted to. Right out of college I moved to Japan to teach."

Ramachandran eventually graduated into copywriting, and a few years later, found himself at Playism as a localizer - a goal of his since first reading an English language copy of Megami Tensei. Now he wears one of many hats for Playism, Kickstarter collaboration being one example. I was introduced to him as a kind of facilitator - the guy you need to know if you want to build connections with Japan's gaming community.

He's one member of a tightly knit community of foreign video game professionals in Japan, many of whom have settled down and started families in their adopted country. Based primarily in the Osaka and Kyoto region, but with a presence in Tokyo as well, they are both making their own games and bridging the gap between Japanese indie developers and the west.

I've been following this community for some time now, mostly through 8-4 - a localization studio comprised of former journalists who are best-known for their popular podcast. I've long been struck by their love of Japanese culture and games, which has bonded together a diverse community, and I've wanted to delve deeper into their unique relationship with their new home. I finally got my chance over the summer, when I traveled to Japan to cover BitSummit, giving me an opportunity to finally meet and interview several of them for the first time.

What I found was a community that has built strong ties to Japanese indie development over the past few years, whether as indie developers themselves or as business people, localizers, or organizers. This relationship was born out of Japan's deep ties to the beginning of gaming, and it's getting stronger by the year.

The Kyoto Triangle

In one way or another, foreigners have been working with Japanese game developers for a long time now. But if the current group has any one seminal moment, it may have been in the summer of 1990, when a small British studio called Argonaut was invited to Kyoto to show Nintendo how they had managed to produce 3D graphics on the Game Boy. Among that group was an 18-year-old Dylan Cuthbert, who had joined Argonaut the year before as a programmer. The story should be a familiar one for Nintendo fans: Nintendo was impressed, Argonaut was given a contract, and the Super FX chip was born.

Cuthbert wound up staying in Japan over the next several years to work on games like X and Star Fox; and in that time, Kyoto left its mark on him. The ancient capital is very different from Tokyo, which is vast, sprawling, and at times, faceless and intimidating. Kyoto in some ways can be compared to Boston, a much more contained and traditional city that mixes equal parts old and new.

"In general, I find that the people in Kyoto are much more down to earth than the people in Tokyo. They're much more relaxed. They're much more friendly, at least. It also comes from the student influx," Cuthbert tells me over a conference table at Q-Games, which sits in a small alley in the heart of Kyoto's business district. "We have all the big univerisities here, so we have a massive student population. It's part of the town, I guess, which adds a lot of the flexibility for the dynamic nature of the town."

Cuthbert has been in Kyoto since 2001, where he runs Q Games - one part of the Kyoto Triangle of independent studios run by foreigners. He has also spent time in the U.S. and Tokyo, but Kyoto is home for him. His love for the city is evident whenever it comes up in conversation, particularly when it's compared directly to Tokyo.

At one point he says of Japan's commercial hub, "You can say you live in Tokyo, but it's very difficult to meetup because everything is so far away from each other. I lived there for three years, and the main thing I disliked about it was that it was very difficult to get people to go and have an izakaya drinkup, because they all have to catch the last train back. It's such a long commute in the first place that they're all tired at the end of it. In Kyoto, three times a week we'd be out drinking, eating, etc. Then you'd go home and crash."

Cuthbert's presence in Kyoto has slowly but surely drawn in more game development; but when he first arrived, there was virtually nothing, he says. "People would be like, 'What are you doing here?' And we would say, 'We're doing our own game for PSN,' and they had no idea what we were talking about. But over the years people sort of slowly gravitated toward Kyoto, and a lot of that was because of the games we were developing. In some way sit put Kyoto a bit on the map. People said, 'They're making games in Kyoto, and it's such a nice place to live.'"

The year after Cuthbert established Q-Games, his friend Giles Goddard - another Argonaut alum - established Vitei, which its best known for its work on Steel Diver for the Nintendo 3DS. Just recently, Jake Kazdal moved to Kyoto to open a branch of 17-Bit Studios, creators of Galak-Z. Kazdal partly credits Cuthbert for the decision, "Dylan and Giles are both old friends of mine. Dylan has been telling me how great Kyoto is for years. He's like, “F*ck Tokyo, you've got to come down here." He’s one of the main reasons we came down to give it a real legitimate look. But between Dylan’s studio, which has probably 20 foreigners, Giles has got 10 or 15. There’s a big non-Japanese game developer community here in Kyoto. Arguably, bigger than Tokyo even. In terms of actual production and developers, especially."

"People would be like, 'What are you doing here?' And we would say, 'We're doing our own game for PSN,' and they had no idea what we were talking about."

On Kazdal's presence in Japan, Cuthbert says, "You know how communicative he is. The best thing about [him moving to Japan] was that he has a very strong connnection to Seattle, which has a vibrant and exciting indie scene. He kind of brought that connection with him, and that brought over even more interest."

The presence of studios like Q Games in Kyoto has created a kind of family atmosphere among game developers. Everyone knows everyone, and there are regular get-togethers at local establishments for drinks, gossip, and networking. Developers who are passing through are also welcomed with open arms, indie developers attending events like BitSummit having become a staple.

BitSummit, as it happens, is another idea that Cuthbert had a hand in developing. Now three years old, the event has slowly grown into a popular attraction for both foreign and Japanese independent game developers. Beginning with 40 developers in what amounted to a high school gym it's first year, it swiftly jumped to 120 exhibitors in its second. At the most recent event, the Indie Megabooth put in an appearance, giving Japanese developers an opportunity to mingle with their western counterparts.

The genesis of BitSummit came about when Cuthbert, Shinra spokesperson and former journalist James Mielke, and handful of others were traveling for the Tokyo Game Show. He remembers Mielke asking of the show, "Where's the indie scene? Why aren't there indie people at the Tokyo Game Show?"

Cuthbert continues, "We sort of thought about that, and realized that the Tokyo Game Show is kind of the publisher based show. Just loads of big publishers showing their big games. It's not really an outlet for that kind of creativity. So that's why Mielke said, 'Well, why don't we do a little event?' And the first event was pretty small. Then Mielke used his ex-press contacts and stuff to bring people over and get it all talked about."

Even now, Cuthbert continues to work tirelessly on behalf of independent game development in Japan. Goddard, for his part, has started Vitei Backroom - a kind of studio within a studio responsible for Fractures, a lovely little puzzle game shown at BitSummit in which a traveler has to unite disparate elements from different worlds to progress.

But while Cuthbert is both a forerunner and a leading figure within the community in Japan, he's certainly not the only one working on the behalf of the indie community there. There are plenty of others, and their influences has grown over the past few years.

The Meetups

It goes without saying, of course, that it's been a rough decade for Japanese game development. Since the advent of the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360, Japanese studios have struggled to keep pace with new technology, rising costs, and changes to the domestic market. It's a problem that has been well-documented be the media elsewhere.

Japan's struggles were captured in the dismissive words of Fez creator Phil Fish in 2012: "Your games just suck." He then later clarified via social media, "I'm sorry Japanese guy! I was a bit rough, but your country's games are f*** terrible nowadays. Well, you know, not ALL of them. Just... a lot of them."

In Boston, a game developer named Alvin Phu was moved to look up "the Japanese guy" to which Fish was referring. He soon found that the developer in question was Makoto Goto, who had worked for Square Enix for many years and had been active in development for the Super Famicom. Phu recalls, "I was like, 'Wow, who's Phil? Who's Phil to say this stuff to such a seasoned developer, such a programmer? I kind of want to be a programmer in Japan someday.' So I contact him online with a bunch of questions, and we talked back and forth a lot."

Goto didn't seem to harbor any ill will about the comments. When Fish announced that he was quitting game development, Goto urged him to continue: "Mr. Fish. You are my goal. I'd like get success such as you by my game. I respect you. Please don't quit." Goto himself is an independent developer.

When Phu later traveled to Japan for vacation, he met with Goto at Otaru - a regular meetup spot for foreign and Japanese developers in Tokyo. There he met a colleague of Goto's who had started up his own game company. Before Phu knew it, he was interviewing for a job. At the end of the night he was told, "If you ever want to come to Japan, just let us know." Phu ended up doing just that.

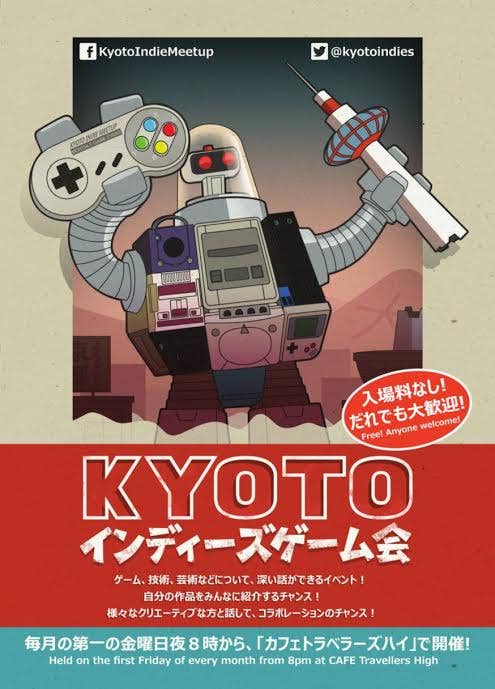

Phu still resides in Japan, having gone independent about a year ago. His current project is Dot Matrix Hero, which his website describes as "part indie game simulator and part roguelike action RPG." In the meantime, he's been organizing monthly meetups at a Shibuya art gallery called Gallery Conceal. In Kyoto, a self-described freelance Unity3D programmer and game designer named Sagar Patel has done much the same.

Phu was motivated to begin running the meetups by his experience with Boston's vibrant indie scene, which is home to events like the Boston Festival of Indie Games. "I'd been to a lot of different game development meetups [in Tokyo]. Some were drinking events, some were workshops. But nothing really that matched that type of feeling of, 'Yeah, you make your own games. If you make your own games, come here, talk shop, hang out, get feedback from other developers, show off your stuff, presentations, things like that.' But more casual. So, I was like, yeah, why don’t I start it? And that’s basically how it came about. I just felt like it’s something that should exist."

The event has grown quickly since kicking off in 2014. It now averages some 70 attendees and features a mix of developers who work full-time for local studios, commercial indie developers, and hobbyists who make doujin games - Japan's traditional outlet for independent development. Developers are invited to show their games, whether it's a work in progress or finished, with the typical format featuring an hour of socializing and an hour of presentations. "I was really worried," Phu says. "Are we going to be able to get anyone? Is anyone even interested in this? The first time I held this, it was at a different venue, really small, and I was expecting there to only be five or ten people. 'Oh, if no one comes, I’ll buy everyone drinks.' And then it turns out we filled out the entire place."

One of Japan's more publicized independent developers, Ojiro Fumoto - better known as Moppin - entered the public eye at one of Phu's events. "[Moppin] showed his game [Downwell] for the first time at the BitSummit around Tokyo Game Show last year, and everyone was like, 'Oh my God, this game is amazing.' We had some media there, too, because they had just come from Tokyo Game Show, I invited them, and they wrote about it, and he got picked up at Devolver Digital."

Events like those hosted by Phu and Patel appear to be proof that a groundswell of support for independent game development has always existed in Japan. The Japanese indie scene has only begun to really blossom, though, nourished by events like BitSummit and meetups like the one at the Gallery Conceal. Phu chalks it up a number of factors, like the prevelance of large studios like Square Enix and Konami in large urban centers like Tokyo. It's also been tough to sell the Japanese on downloadable games, with magazines like Famitsu refusing to cover them until recently.

"Startup culture is starting to get pretty popular here, but, that’s still early. Anway, yeah, staying with the company, it’s still a strong ethos here. Breaking out of it - also, being financially viable, that’s the hardest thing about being indie, especially, moreso, in Japan," Phu says. "The thing is, it’s sort of tricky. Like, of course everyone wants to make their own thing, but also, they got to eat, too. Some of those older developers... Those people have grown up, they had significant others, kids. It’s like, 'Well, I can either quit the game industry, or, go to social mobile.'"

In recent years, though, more and more developers have become disillusioned with established publishers and heavily monetized mobile developers. Creators like Yoshirou Kimura (Little King's Story) have struck out to create games like Brave Yamada (???????) - a brilliant and rather hilarious mobile game that mixes RPG and puzzle elements. Another developer quit a Japanese middleware company to create Back in 1995, which uses cutting edge technology to make Unity replicate the look of a very early 32-bit game - warts and all.

The scene is young, but it's growing. And Phu's event is just one place where they're coming together.

Kickstarting Attention in the West

Phu and Patel aren't the only ones hosting events, of course. There are the drinking events hosted by Cuthbert and company in Kyoto, and there's Otaru in Tokyo, which is typically hosted in part by 8-4. Ramachandran knows all about such meetups, having hosted plenty of them himself under the umbrella of Playism. And like Phu, he's been there to watch as the Japanese indie community has steadily grown.

Nayana Ramachandran is particularly familiar with Japan's doujin game development community. Japan's homebrew community has existed since the dawn of gaming, and can in many ways be considered the original indie development community in that country, being somewhat akin to modders in other countries. Often, a software developer will work 10 hours at a typical corporate job, then go home and spend several more hours working on a game. When they're finished, they will often bring it to local comic markets and distribute it for free.

Playism has made a business out of seeking these games out, localizing them, and selling them abroad. Ramachandran remembers, "We were working with the developer for One Way Heroics, which is sort of a roguelike mixed with a JRPG overworld. It's one of my favorite games we've ever worked with. But when we first met the developer, he was a systems engineer who was releasing his game for free with Paypal donations on his site. And we met up and said, 'We want to localize this game, but this game is huge and has a ton of text, so we're oging to have to charge for it.' And he was like, 'Hey man, if you think you can get away with it, then go ahead.' So we released it in the State, and people actually told us that it's too cheap. They said, 'You should make it more expensive.' And the game did so well at $3.49 that he was able to quit his job and make video game for a living. What's so satisfying about it is that we felt validated in saying, 'Yeah, Japanese indies have a future in the west.'"

While Q-Games, 17-Bit, and Vitei are based in Kyoto, Playism is in neighboring Osaka. Founded in 2011, they have managed to work their way into many different aspects of the Japanese development community, particularly the indie segment. They host events, stream games for the west, and generally try to do their part to evangelize for the Japanese indie scene.

With Twitch having only recently established a branch in Japan - the majority of Japanese gamers utilize Nico Nama, which is the domestic equivalent - it's tougher for Japanese indie developers to gain exposure in the west using traditional outlets, though things are shifting a bit. Thus, Playism streams what they can. "There's so many times where we've streamed games where people will be like, 'What is this game? I've never seen this before.' The truth is that a lot of these games just need to be in front of people, and they'll realize that it's actually really cool," Ramachandran says.

The explosion of Kickstarter and other crowdfunding sources have offered another outlet for promoting Japanese indie efforts in the west. The Mighty No. 9 Kickstarter is a well-documented example of the expat community in Japan coming together to help a project succeed, from 8-4 to Ben Judd (Bionic Commando: Rearmed). Playism wasn't associated with that project, but they've since picked up the ball and run with it, becoming experts in their own right. The Kickstarters for La-Mulana 2 and Koji Igarashi's Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night were both spearheaded by Playism.

"We were working with the developer for One Way Heroics, which is sort of a roguelike mixed with a JRPG overworld. It's one of my favorite games we've ever worked with. But when we first met the developer, he was a systems engineer who was releasing his game for free with Paypal donations on his site."

Ramachandran admits that plenty of people were skeptical that Kickstarter could be made to work in Japan. "Even when you introduce people to Kickstarter in Japan, even if they understand generally how they work, the thought process behind why someone backs a project is truly alien to the developers. How you work with them, or how you get them what you want, is very, very different from what they're used to."

He continues, "Traditionally, Japanese developers have not had that personal connection with the fans that western developers do. They want that, but it's not something they're used to. So it's a learning process. And just having to take a leap with that sort of thing. Kickstarter is all about leaps of faith. 'It's going to be a good idea, don't worry.' And sometimes that's really hard. They really just want to be, 'Give me assurancees this is going to work.' And I say, 'I can't do that.'"

As Kickstarter has developed a proven track record in Japan, though, Ramachandran says that he has had an easier time getting Japanese developers to trust the process. "Working with Igarashi-san on Bloodstained, he was totally open to so many things that most developers would be like, "No, that's not a good idea." He was just like, 'I trust you guys. Go for it.' Half of that is really a testament to Igarashi himself. He's a really humble guy."

These days, Playism is busier than ever hosting parties, attending events like TGS, and pushing games. The Bloodstained Kickstarter closed in June after raising $5.5 million in pledges; and with more and more and Japanese developers exploring different funding options for personal projects, Playism figures to keep busy in the coming years. For Ramachandran and company, life is good.

"I Want People to Think that Japanese Indies are Doing So Well that it's Scary"

In some ways it's easy to put too much emphasis on the work of foreign gaming professionals living in Japan. Being a westerner myself, I'm naturally biased toward perceiving what's happening in the English speaking community. At the end of the day, studios like La-Mulana's Nigoro are winning over fans abroad with terrific games. The various western developers I spoke with in Japan were all at pains to downplay their influence and give credit to the creators.

Cuthbert is particularly adamant on that front, "When we started BitSummit, we said we just wanted to introduce Japanese devs to western media and facilitate a conversation between the devs because everyone gets into their own little thing, and they don't want to share or talk. Coming from the west, we saw how all the indies were kind of collaborating, so that was the goal in the beginning. But we never wanted to be like, 'This is how we do it. We're Q Games.' So we didn't even really get out in front of the first [BitSummit]. That's why I don't really go out in front of it either, because I don't want it to be centered around this foreigner who lives in Kyoto kind of thing. We try to avoid that. We just help them communicate with the west, because that's where we're strong, right? Then they can basically learn from that, I think."

He points out how Pygmy's Hisashi Koshimizu runs the actual show, but how that element tends to get passed over because it's in another language. "Mielke will come up and do his English speaking bit, or Ben Judd. But the other people speaking are all Japanese. So they see a slightly less western-oriented side of BitSummit than we do, because we naturally bias ourselves toward the English-speaking side."

Still, the energy and passion in Japan's foreign development community brings to the table speaks for itself. It speaks to the formative influence Japan has had even for someone like Cuthbert, who grew up with the ZX Spectrum rather than consoles. They care deeply about the success of Japanese games at home and abroad.

"One of the big things for Playism going forward is to not just publish things and make people money. We always want to facilitate the community. Host events. Host lectures. We want the Japanese indie scene to be at the point where when western indies show up, they'll say, 'Oh s**t, this is what Japan is doing? We're so screwed.' I want people to think that," Ramachandran says. "I want people to think that Japanese indies are doing so well that it's scary. Because that was the level of development in Japan about 15 years ago. And I want Japanese indies to be at that point, because they deserve to be. They have so many talented people."

See what I mean?

Ultimately, they will do anything they can do help. As an example, Ramachandran points toward the need to figure out how to get more outside funding for indie development in Japan. With BitSummit, at least, as well as the meetups in Tokyo, Kyoto, and elsewhere, the Japanese indie community has a way to come together. One of the most important roles of the show has been to bring together developers and let them see each other's work, spurring them on to greater heights.

Mostly, English speakers living in Japan can spread the word in their countries that Japanese indie development not only exists, but that it's on the rise. Alvin Phu describes what he encountered when he came back to Japan, "I went to GDC and everyone said, 'Hey, what's the indie scene like in Japan? I heard it's like nothing.' And I was like, 'Not at all.' A lot of foreigners here just want to help out Japanese developers that they know. What else can we do?"

On the last day of BitSummit, I found my way to a little bar where the after party was in full swing, with creators who were in town to show games like Assault Android Cactus and Videoball mingling with the local expat community and Japanese developers. Moppin came in at one point and he was greeted like a conquering hero. Everyone was upbeat after a packed show.

Their optimism is infectious. After a rough decade, it seems we have plenty to look forward to out of Japan.

Correction: This article previous said Playism was "tangentially involved" in the Mighty No. 9 Kickstarter. Playism has clarified that they did not have a role in the project.