Dungeon Keeper: A Symptom of a Wider Problem

How EA and Mythic's reimagining of Bullfrog's classic strategy series is just the tip of the iceberg.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"We don't have a mobile gaming industry any more," wrote new media commentator Thomas Baekdal over the weekend in reference to EA's new mobile version of Dungeon Keeper, "we have a mobile scamming industry."

This may sound like hyperbole, but sadly, we're far beyond that now. Dungeon Keeper isn't the first example of a business model completely destroying any semblance of gameplay or fairness from a mobile title, and I'm pretty certain it won't be the last.

For the few of you reading who might still be unfamiliar, Dungeon Keeper was originally a series of real-time strategy games developed by Peter Molyneux and his Bullfrog team for PC. They were fondly regarded for their dark sense of humor, solid gameplay and interesting take on the usual tropes of the fantasy genre -- even today, it's still relatively unusual to have the opportunity to play as "the bad guy."

EA's new mobile version is superficially similar to the original Dungeon Keeper games in that you dig out tunnels to make space for rooms, slap imps about to "motivate" them and then defend your dungeon against intruders. There are several key differences, however: the most minor is the fact that the game's original aesthetic has been replaced by a distinctly Zyngafied look, with bland, cartoonish characters rather than the stylized creatures of the original; the most major, meanwhile, is that everything you do in the game -- from digging out a single square of rock to constructing a trap -- takes varying amounts of real time, and can be "rushed" by spending the game's premium currency of gems.

And with even the most simple tasks occasionally taking up to 24 hours of real time to complete -- yes, digging out a single square can take a whole day -- EA is counting on impatient players to want to spend those gems as quickly and as often as possible, and as such has provided in-app purchase options that extend all the way up to $100 at a time to facilitate the collection of said gems.

Beneath the freemium exterior, EA's mobile version of Dungeon Keeper isn't a very good game, either. Once you've built your dungeon and someone invades, all you can do is hope that the game's rudimentary AI system doesn't behave like an idiot; similarly, if you decide to "raid" a rival player's dungeon, all you can do is choose where to drop your troops, not command what they do or where they go. Actual "strategy" is minimal; it's simply a case of buying the most powerful things you can afford, giving rich players an immediate and insurmountable advantage.

Herein lies a serious problem with the mobile games industry as a whole right now: good game design is frequently sacrificed in the name of making something more likely to make money. Players are not respected as people who want to have fun; they're treated as resources who need to be exploited. "Friction" is created by making players wait, or by not quite giving them enough money to do something, or, in some cases, by limiting the number of actions they may take in a single day through an energy bar or lives system, and the only way to alleviate the "fun pain" that "friction" creates is by paying.

EA's Dungeon Keeper is far from the sole offender in this regard, either. The most popular games on mobile, such as Supercell's Clash of Clans, EA's The Simpsons: Tapped Out and Kabam's "midcore" strategy games, all follow this model. The "best" Clash of Clans players in the world rise to the top rankings on the leaderboards not through skill, but through how much money they're willing to spend, as this eye-opening report from Wired describes. Does that sounds like a good, fair experience?

The most common counter-argument at this point is that mobile games, more often than not, aren't designed for people who have been playing for years. Instead, they're designed in order to capture a more casual market -- one for whom their mobile phone or tablet might be their first ever gaming-capable device.

Okay. I see the point. But I fundamentally disagree with it, for several reasons. Firstly, if Dungeon Keeper, like Theme Park's iOS incarnation before it, is designed to ensnare a casual, non-gamer audience, why give it the name of a series that carries a lot of fond memories for gamers of a certain age? As mobile core gaming site Pocket Tactics quite rightly points out in this piece, the demographic most likely to respond to the Dungeon Keeper branding -- those over the age of 25, who were around for the game's original incarnation -- are also the least likely to pay up for a freemium game, according to the NPD Group's research.

And as for the second point -- the fact that it's designed for casual gamers, who don't seem to mind this sort of thing -- consider this. More and more new players are being introduced to gaming on a daily basis, which is great for our hobby as a whole, but it's happening through some of the worst examples of 1) game design and 2) business models. Casual players don't complain about this sort of thing so much because, in many cases, they don't know any differently. Had they been introduced to gaming through something equally casual-friendly but less heavily monetized, they may well feel differently. But, sadly, with the marketing clout of companies like EA -- not to mention Apple picking Dungeon Keeper as its Editors' Choice app on the App Store, thereby giving it a significant amount of exposure -- the unscrupulous, unethical, poorly designed games like Dungeon Keeper rise to the top of the charts and then stay there, preventing anything a bit more friendly to the consumer from rising to the top, and helping to establish "free with in-app purchases" (or "pay to win") as the norm rather than the exception.

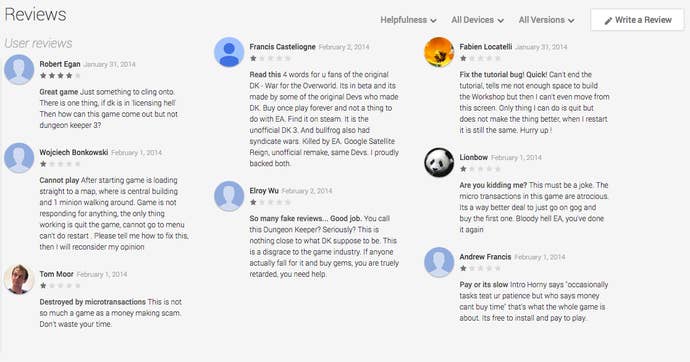

This then gives the developers and publishers of these games leverage to justify their business decisions. When confronted with negative feedback regarding the new Dungeon Keeper on Twitter, senior producer at developer EA Mythic Jeff Skalski simply noted that "we made a game for mobile gamers and they like it," pointing to the nearly 30,000 5-star reviews on the game's Google Play page. However, as the less scrupulous members of the app development community well know, star ratings and reviews are very easy to manipulate, as any number of fake Minecraft apps with abnormally high ratings on both the iOS App Store and Google Play will attest -- the key thing to look at is what people are actually saying in the reviews. And, well, the user reviews don't paint an altogether pretty picture on Google Play:

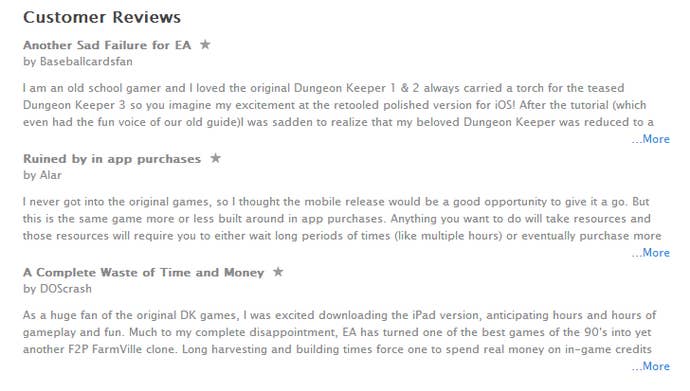

Or the App Store, for that matter:

These aren't cherry-picked reviews, incidentally -- they're the ones that appear when you simply go to the app's page at the time of writing. They're what people are saying right now.

So what did Skalski mean by "we made a game for mobile gamers and they like it?" He later clarified in a couple of follow-up tweets by explaining "if I built a $7 game a fraction of the gamers would download it. I know us classic gamers feel f2p has tainted the industry, but mobile gamers want free. They decided it not me. I'm building what they want. They are the client."

The sad thing is, he's sort of right, thanks to the reasons outlined above. Mobile game pricing has been proceeding on a race to the bottom for the past few years, with prospective players -- many of whom are coming to gaming for the first time via mobile devices, remember -- conditioned to balk at the idea of paying more than 99 cents for a mobile game. It's also this thinking that leads people to deride companies such as Square Enix for charging up to $20 for a deep, solid, in-app purchase-free game -- even when said game offers 40-50 hours of entertainment equivalent to something you'd get on a dedicated gaming console such as Vita or 3DS. Instead, millions of people download free apps to "try" them, get hooked in by psychologically manipulative basic mechanics -- usually of the Skinner Box variety -- and are then nudged in the direction of the payment options, usually by foul means rather than fair. The sheer number of people that these tactics work on drives these games to the top of the Top Grossing charts on the App Store, where they stay for months at a time. It's no surprise that more and more developers and publishers want a piece of that pie, in turn compounding the problems outlined above.

What's baffling about all this is that PC gaming has got free-to-play so right, and in doing so proven that you don't have to sacrifice solid production values and well-designed games to make a profitable freemium experience. Experiences such as Dota 2, Team Fortress 2, Path of Exile, Hearthstone and League of Legends all prove that it's possible to put out a game for free, provide a satisfying and solid experience for non-paying players, and provide those who enjoy the experience the opportunity to slip the developers a bit of money to show their appreciation. In exchange, those paying players are rewarded with some goodies that don't break the game -- a stark contrast to many mobile games, which punish free players rather than rewarding those willing to open their wallets. In titles such as Dungeon Keeper, you're all but obliged to spend money in order to remain competitive -- or simply, let's not forget, if you don't want to wait a whole day to dig out a single square of dungeon.

So what do we need to do to rectify this situation? Well, sadly, as Baekdal writes in his article, it's questionable as to whether or not it may be too late to do something now, since it's become such an accepted part of mobile gaming culture that devs like Skalski can say things like "we made a game for mobile gamers and they like it" -- and what a lack of respect that shows for "mobile gamers" -- with a straight face. But that doesn't mean we should stop speaking out against it when particularly egregious examples show their faces; it doesn't mean we shouldn't try and educate newer, more casual gamers about the alternative, better, fairer ways that the games biz can work; and it definitely doesn't mean that we should be apologists for this sort of behavior when it's exhibited in other games.

Don't stand for games that hold your time to ransom. Don't reward developers and publishers for poor game design by handing them a few dollars "because it's not that bad." (I'm looking at you, Tiny Tower fans; that game follows most of the same freemium conventions as Dungeon Keeper is using here -- it's just somewhat more generous with what it gives you for "free.") And if something is put up on the App Store or Google Play marketplaces for no up-front cost, do yourself a favor and check the list of in-app purchases before you download it -- if there's the option to spend upwards of $100 in a single transaction, you may want to think long and hard about whether the game in question is something that's really worth supporting at all, even with a download.

Consumers and press alike are right to criticize Dungeon Keeper as much as it has been so far. There are hard-working developers and publishers struggling to bring meaningful, beautiful game experiences to mobile platforms -- and yet their hard work is undermined by games like this simply seeking to make a quick buck. The great experiences we can have on mobile devices -- The Year Walks, the Rooms, the Device 6s, the Papa Sangres, the Sword and Sworceries of the world -- are fast becoming the exception rather than the rule, and for a platform that showed such massive creative promise when it first opened up in the years before in-app purchases, it's distressing to see the quality games and passionate developers constantly pushed aside by yet more derivative, cynical, free-to-play titles.

Readers, please don't support garbage like this. Few of us would like to contemplate a future where this sort of thing is the accepted way that games "work" -- and yet with the rise of "paymium" features in next-gen games such as Forza 5, we're running the very serious risk of the absolute worst aspects of mobile gaming spilling over into other sectors. Let's not allow that to happen.