In Death Stranding and Red Dead Redemption 2, triple-A has embraced boredom

Set in the heart of Montana’s Big Sky Country, Far Cry 5 is a game that begs you to look up - taking in the fluffy clouds and Warner Bros-style water towers, sniffing at the scent of douglas fir like car air freshener. But it doesn’t ever let you have that moment with its world, because what travels on the air is the constant washboard rattle of gunfire. The gentle rustle you thought might be breeze through the trees? That’s a bear hurtling towards you in the undergrowth, ready to smack you out of your trance with a heavy paw.

Far Cry 5 is typical of open worlds as we’ve known them over the last decade - a paradigm that might only now be changing with the likes of Red Dead Redemption 2 and Death Stranding.

Ubisoft chief creative officer Serge Hascoet likes to call the company’s open worlds “anecdote factories”. As CEO Yves Guillemot explains to Polygon: “Serge had a vision of creating worlds as playgrounds, full of systems and toys that let the players have more personal experiences they would be eager to share with friends and the community.”

These anecdote factories focus on emergent encounters as much as scripted sequences - the kind of stories that come from enemies and environmental features clashing in unexpected ways. The term was used during the promotion of both Watch Dogs 2 and Far Cry 4, the latter of which notably dialled up the frequency and ferocity of encounters in the wild. Arguably too much.

Ubisoft’s restless, screaming worlds are symptomatic of a worry among game designers - that if you don’t happen across their carefully curated systems quickly enough, you’ll slink off to play something else. Like the salespeople in a car showroom, they’ll never leave you alone for fear of losing you.

That desperation is becoming unsustainable as open worlds get bigger. Triple-A games are increasingly designed as hobbies, meant to occupy your every waking hour and pull in funds far beyond their box price. Modern Warfare can get away with a five hour campaign because the real timesink is the multiplayer. Single player-focused open worlds, though, simply get longer and longer.

How Long to Beat suggests it took the average Assassin’s Creed Unity player a little over 33 hours to finish; Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, by contrast, has an average completion time of almost 86. That length in itself is a money-maker, since players will pay to shorten playtime - recent Ubisoft open worlds have sold currencies and items to boost progress.

“Our goal is to make sure you can have a Unity within an Odyssey,” Guillemot told GamesIndustry.biz. “If you want to have a story of 15 hours, you can have it, but you can also have other stories. You live in that world and you pursue what you want to pursue. You have an experience, many Unity-like experiences.”

While it might have been possible to structure a 15 hour story like an action movie, the task becomes absurd as playtime creeps into triple figures. That endless stream of high octane encounters is bound to get old. In this new context, developers are forced to embrace downtime.

Rockstar was perfectly placed to do so. Although responsible for popularising open worlds, it’s always been an outlier, content to let mundanity creep into GTA. Think of all those times your ride exploded out in the sticks of Liberty City, leading to a long jog back to the nearest road, the only action on-screen the flutter of newspapers on the wind.

Where other open world specialists have finessed these moments out of existence with instant fast travel, Rockstar has only doubled down on the downtime. Red Dead Redemption 2 is meditative in its pacing, committing to the slow burn simulation of late 19th century life. It exists on the membrane between the wilderness and the modern world, and that’s not a time defined by its conveniences; there’s no fast travel without stagecoaches or trains, at least until you upgrade your camp.

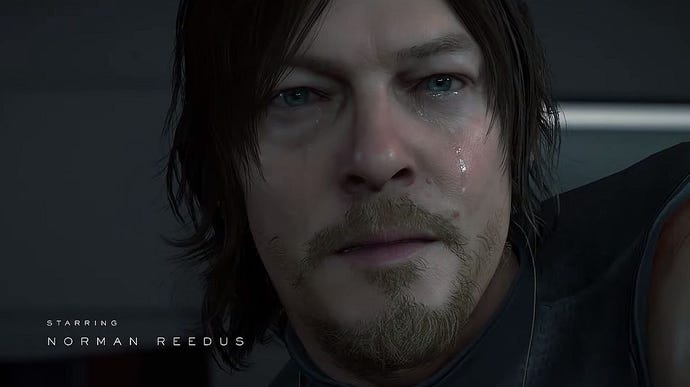

It’s an approach that rubbed some players up the wrong way, and no wonder - we’ve been conditioned to expect worlds to offer up action within seconds. It’s been the same story with Death Stranding which, while not as accomplished as Red Dead, explores similar territory. This is a game about carrying cargo over long distances on your back - a two-legged American Truck Simulator. Since you’re linking up a devastated US, there’s little infrastructure for you to take advantage of yourself.

It’s long and lonely work, designed to starve you of connection so that when those encounters do come, they’re significant. As in Red Dead, combat and conversation is lent far greater tension and meaning by the spaces in between.

Ultimately, Kirk deemed Death Stranding too repetitive in his review - but it’s a positive and necessary step as developers fiddle with the dials to discover how much downtime is too much. What they’re realising is that long stretches of very little are exactly what grounds you in a world. And that without grounding, you can’t have electricity.