Daily Classic: The Final Fantasy Legend, Portable Role-Playing's Esoteric Start

25 years ago, the world's first handheld RPG was also Squaresoft's most daring creation.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

When Nintendo's Game Boy debuted in Japan in April 1989, it marked the dawn of a completely new form of video games. Sure, handheld games had existed prior to Game Boy, but those precursors had been limited at best.

Unlike Game & Watch or Epoch's Pocket Game Computer, the Game Boy had the power to recreate console-caliber experiences on the go, albeit with some compromises. Even so, it may come as something of a surprise to learn that Game Boy's first proper role-playing game arrived just half a year after the system itself. As one of gaming's most complex and resource-intensive genres, RPGs typically don't begin to appear on new consoles for a year or more after that platform first arrives.

But Squaresoft embraced the new console enthusiastically, launching an entirely new franchise to go along with the handheld's entirely new mode of play. While The Final Fantasy Legend bears the name of the company's other RPG franchise — already a solid success in Japan by 1989 — that moniker applied only to the U.S. release. In Japan, FF Legend went by the title "Makai Toshi Sa•Ga," later shortened simply to SaGa.

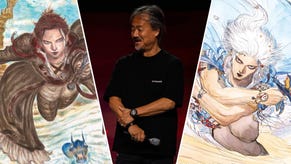

SaGa would go on to become Square's second longest-running series behind Final Fantasy; though it's been fairly inactive over the past few years, a new title called Emperor's SaGa is reportedly in the works. However, its life has hardly been as beatific as Final Fantasy's, and it comes by those travails by design. While Final Fantasy has increasingly bent toward mainstream appeal, SaGa has featured a deliberately design philosophy courtesy of its mercurial creator and producer, Akitoshi Kawazu; a tradition that's been true of the series since its inception.

Kawazu had been one of the designers on the original Final Fantasy, and when the sequel rolled around, he stepped in as lead designer. Final Fantasy II is probably the single most controversial and unloved main entry of the Final Fantasy franchise, bringing with it sweeping changes and unconventional mechanics. It abandoned the straightforward concept of character levels, instead parceling out stat boosts based on each character's actions in battle. Use a spell, their magic power (and the potency of the spell itself) would improve; attack with a sword and their sword skills would increase.

A good and logical approach on the face of it, in practice FFII's mechanics proved to be wildly unbalanced — front-line fighters would become devastatingly powerful, while the rear guard would rarely take a hit in combat and thus remain fragile throughout the adventure. Players compensated for this by grinding out stat boosts through attacking their own party members and burning through magic spells in order to level them up. The system, unsurprisingly, didn't make a return appearance for Final Fantasy III... and neither did Kawazu.

Instead, Kawazu resurfaced on Game Boy with SaGa, aka Final Fantasy Legend. In a way, it offered both the creator and his company the best possible compromise. Kawazu's approach to role-playing design proved to be an ill fit for Squaresoft's flagship series, but rather than simply quash his creative impulses they instead gave him an alternate outlet. As a new creation on an untested platform with modest production requirements, SaGa gave Kawazu a chance to experiment to his heart's content.

The work he and his team came up with didn't disappoint. SaGa managed to be remarkably esoteric, with a number of opaque and sometimes mystifying mechanics, yet at the same time it all fit together far more effectively than Final Fantasy II had. Freed of the restrictions of someone else's creation, SaGa could simply be its own thing — decidedly not a Final Fantasy adventure, despite its American title.

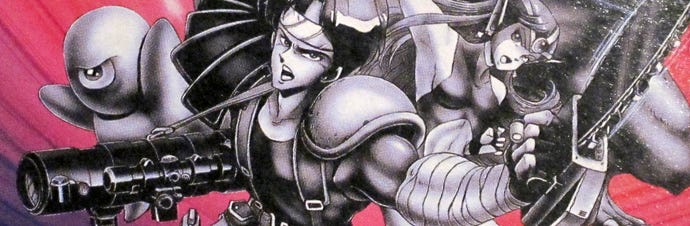

Nothing about SaGa looked like your typical RPG, beginning with the cover art. A manga-style warrior glared out at prospective buyers, clad in strange armor and wielding the rather unconventional combination of a rocket launcher and chainsaw. Behind him, an elven enchantress dressed in sports wear, a strange one-eyed blob of a creature, and a towering dragon braced for action.

Equally quirky was the game's premise: The player's party had to ascend the tower at the center of the world, an impossible construct that contained multiple planes of reality while being contained within those realms as well. Along the way, they took on the four deities of the Chinese Zodiac and did battle with a number of minor thugs as well.

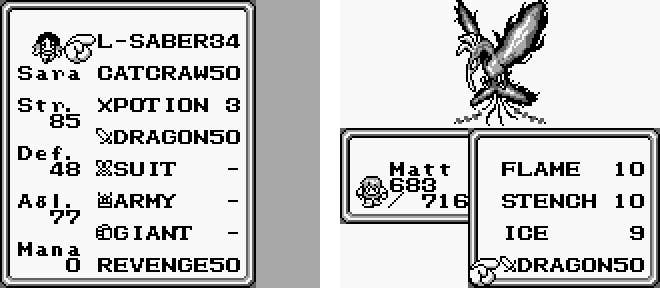

SaGa didn't incorporate the same leveling mechanics as Final Fantasy II, but neither did it walk the straight and narrow of its console RPG brethren. Players could roll their own party of four warriors from three different races: Human, Mutant, and Monster. Each had its own strengths, along with its own specific quirks. Humans had powerful physical stats but would eventually hit a ceiling on stat growth, and could only level up by using permanent consumable items. Mutants (Espers in the Japanese version) could wield powerful magical spells, but they could only memorize a small number of spells at once and there was a decent chance that one of their spells would randomly be replaced by another at the end of a battle. And Monsters demonstrated no stat growth whatsoever; instead, they could devour the meat of fallen enemies to mutate into other forms (sometimes more powerful, sometimes not).

The randomness of Espers and complex rules of Monster growth (so nuanced and opaque as to seem random for anyone not using a guide) made SaGa an unpredictable and sometimes unfriendly experiences, especially for RPG newcomers. On top of that, spells and powers suffered degradation; Human weapons would eventually break, while Monster and Esper skills had to be recharged by sleeping. SaGa also featured a permanent death mechanic, which would go under the name Life Points in future entries: When defeated in combat, a party member would permanently lose a Life Point. Once completely depleted of Life Points, a character could no longer be resurrected, and restoring Life Points came at considerable cost.

While all of these features may sound infuriating on paper, within the game they actually work. SaGa operates on its own rules, and it's comfortable and confident with itself. It doesn't feel like a bog-standard RPG trying to stand out but rather a game designed deliberately to stand apart from the rest. Its fascinating (if curt) story and gorgeous music made it feel far richer than other early Game Boy titles, too — like a proper video game rather than something jammed down to fit the format. And its creators demonstrated remarkable thoughtfulness in creating such a large, demanding adventure for a portable system: SaGa allowed players to save at any time outside of combat, a feature more portable RPGs would have been wise to incorporate through the years.

The SaGa series would continue through the years, seeing sequels on Super Famicom, PlayStation, and PlayStation 2. It's never seen success on the scale of its sibling Final Fantasy, but that's hardly surprising given that the games, at times, seem to be almost daring players to enjoy them. For those willing to take up the challenge, though, the SaGa games still offer an experience as unique and nuanced as Final Fantasy Legend did 25 years ago.