Daily Classic: 25 Years Ago, Mother (aka EarthBound Zero) Skewered JRPGs, and America

While lacking the polish of its sequel EarthBound, Nintendo's first true RPG still marched to its own beat.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

You have to admit, Japanese gamers took to role-playing games with surprising fervor. The Black Onyx opened the door to the genre in 1984, and within five years the format had grown so pervasive and standardized that it had already begun to inspire parodies.

Admittedly, Nintendo's Mother isn't exactly a parody in the sense you might expect. It doesn't lean on broad jokes or feature characters mugging for the camera. It lacks the mean-spirited bite of South Park or the apathetic use of pop-culture references in place of actual jokes common to television shows like Family Guy. It takes a more subtle, even gentle, approach, standing somewhere between satire and pastiche.

Specifically, Mother sets its sights on the Dragon Quest series, which (despite not having yet made its way overseas by summer 1989) had exploded into a juggernaut in Japan since its debut three years prior. Dragon Quest III, which launched about a year and a half before Mother, had become a newsworthy phenomenon, inspiring long lines of fans eager to be the first to play this hotly anticipated sequel... many of whom were kids who skipped school and ended up being arrested for truancy. While role-playing games of all varieties — from dungeon-crawler to roguelike — found a welcoming audience in Japan, only Dragon Quest could rack up first-day sales exceeding a million.

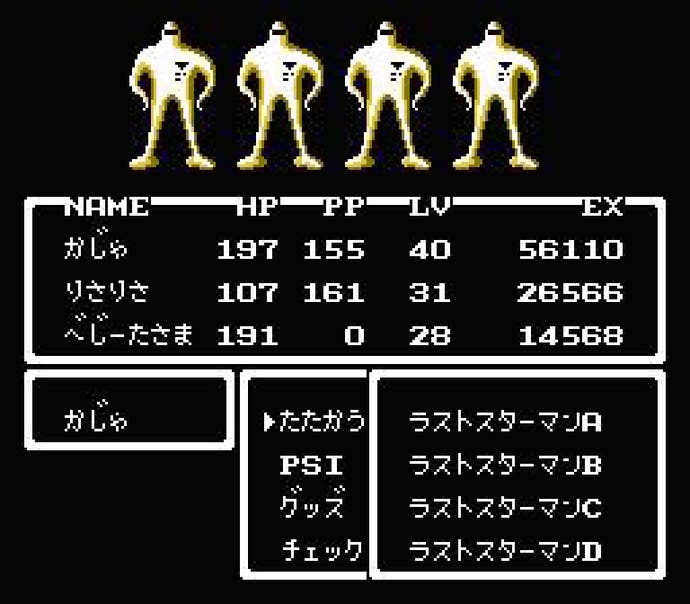

A great many Japanese RPGs used Dragon Quest as a template, borrowing a similar graphical style, a similar first-person combat view, even lifting the interface display windows directly from Enix's hit series. In this respect, Mother simply looked like yet another Dragon Quest knockoff.

Where the game differed from the rest was in its setting and story. Unlike every other Roto-come-lately to clog up the late '80s Famicom release lists, Mother scrupulously avoided the hoary clichés of fantasy or science fiction that dominated the rest of the genre. Instead, it presented its tale framed in the context of the modern world. In that sense, Mother wasn't wholly unique; Atlus and Namco had published Digital Devil Saga; Megami Tensei nearly two years prior.

But Mother and MegaTen couldn't have been more dissimilar in their approach to the modern day. MegaTen transpired in Tokyo and quickly shifted to a sort of horror-tinged demon world inhabited by fantastic creatures culled from the religions and myths of the world, and it deftly blended science fiction and fantasy. Mother, on the other hand, sent players into a thinly veiled rendition of America — the USA as seen through the eyes of a Japanese author, all iconic images and skewed clichés — and while eventually the plot did culminate with a decidedly sci-fi scenario, it never lost its grounding in that slightly offbeat version of modern America.

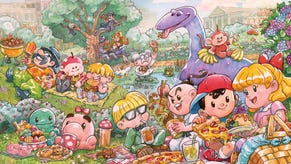

It probably helped that Mother unfolds from the perspective of a young boy (roughly 10 years old) rather than the high school students who take the lead in Megami Tensei games. There's a sense of wonder and magical realism that makes sense in the context of childhood imagination; Mother forever leaves players wondering what's presented literally and what's simply an invention of its young protagonist Ninten. While other RPGs cast players as a hero like in Dragon Quest, Mother at times feels more like you're taking the role a child pretending to be a hero like in Dragon Quest, a conceit adopted more literally in recent years by the likes of Costume Quest and South Park: The Stick of Truth.

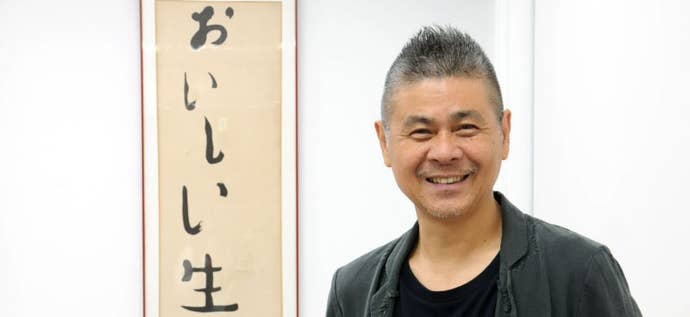

By and large, the unique nature of Mother can be chalked up to the creative vision of the driving personality behind its design and story, writer Shigesato Itoi. A prolific and multi-faceted author, Itoi's closest analog in the U.S. would probably be Garrison Keillor — both share a similar warmth, and the likewise share a common appreciation for childhood experiences and nostalgia matched to the ability to good-naturedly skewer such things with the wisdom and cynicism of adulthood.

Mother came about through Itoi's initiative, and he provided the full text of the game — not only the critical quest dialogue, but the musings and remarks of non-player characters as well. This fact alone helped elevate the game above its peers; rather than being written by game designers, Mother was written by a writer.

As a writer, Itoi specializes in saying a great deal in very little space. He's worked for years as a commercial copywriter, and he produced daily "micro blogs" long before Twitter existed. This talent for crafting economical, multi-layered copy made a perfect match for an 8-bit RPG, where storage space came at a premium and every byte of text had to count. Conversations in Mother spanned the gamut from surreal to humorous to wistful, a far cry from the perfunctory, functional text common to other console RPGs. Mother's NPCs would contemplate the profound and the trivial alike rather than simply ruminate on matters relevant to the plot or the quest at hand.

The real-world grounding of the game found form in Mother's mechanics as much as in its conversations. Ninten and his friends wielded weapons like baseball bats and toy guns rather than legendary swords and assault rifles. Players could travel by train instead of simply moving from town to town on foot, and you were as likely to see a dungeon take the form of an abandoned warehouse or laboratory as a cavern.

At heart, sure, Mother still worked like your typical Dragon Quest variant. Random combat encounters would transfer players from overhead exploration sequences to first-person combat driven by menus. Hitting bad guys with baseball bats functionally worked the same as slashing with Excalibur in some other RPG, and magic spells still played a critical role in battle, even if the story tried to pass them off as psychic powers.

And in truth, Mother was a fairly uneven example of the console RPG format. The game suffered from a number of rough edges; the party's offensive and defensive stats didn't scale consistently with the threats they encountered, causing the difficulty level to rise and fall wildly from area to area. Most of the mechanical refinements that people love about the sequel, EarthBound, don't appear here. Rolling HP counters, non-random enemy encounters — those are features from EarthBound, not Mother.

In one of the great cases of "the ones that got away," Mother was originally slated to be localized for the U.S. under the title "Earth Bound," but those plans fell through and the name was reassigned six years later to the U.S. release of Mother 2. A complete localized version was unearthed years later and made its way onto the Internet under the name "EarthBound Zero," but in a way its failure to make its way to the U.S. has only helped to prop up its sequel's legacy as a unique and special creation. While Mother featured writing every bit as sharp as EarthBound's, the game mechanics wouldn't catch up with the narrative until the 16-bit era.

Even so, the mere fact that Dragon Quest inspired such enthusiasm as to warrant a game that deliberately skewed its foundations — headed up by a well-known writer, no less — speaks volumes of how quickly Japan cottoned to the genre. And in that satirical adventure, we see just how idiomatic that country's rendition of the concept became almost from the very beginning. Mother may have belonged to the same genre as Curse of the Azure Bonds, but as an expression of the RPG concept it couldn't have been more different.