Curtains for You: The History of Bullet Hell

An exploration of the shmup genre's most challenging offshoot.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Shooting games - also known as shoot 'em ups, shmups or STGs depending on how "into it" the person you're talking to is, and not to be confused with first-person shooters - are one of the most venerable genres of video games, having been around since the medium's inception. Indeed, what is widely regarded as the very first computer game - 1962's Spacewar! - involved the now-familiar sight of spaceships floating around and shooting at each other, albeit in a competitive two-player scenario rather than pitting a single player against the game itself.

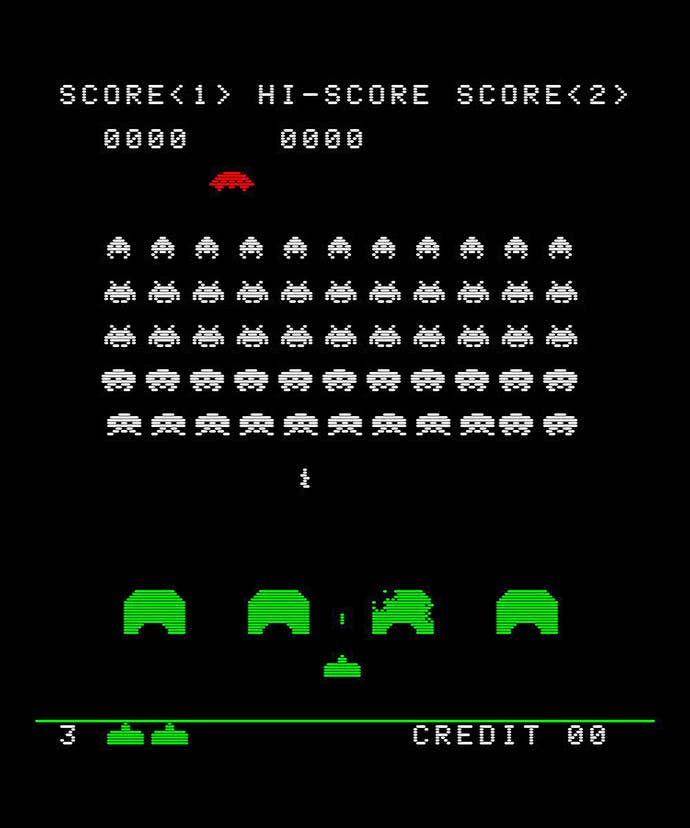

It wasn't until Taito's 1970 release of Space Invaders that the genre started to gain some degree of mainstream recognition, though. Space Invaders' predictable waves of enemies and ever-increasing difficulty may not bear much resemblance to the shmups we play today, but it was a starting point for a genre that would blossom into a variety of different play styles over time. All the key ingredients were there: a single player sprite tasked with battling against seemingly insurmountable odds; gameplay that involved dodging incoming fire as much as shooting accurately; and the ever-present feeling that if only you had just one more go, you'd be able to best your high score.

Following the release of Space Invaders, game developers explored a variety of different ways to make shooting endless hordes of enemies more fun, and in the process begat a number of shmup subgenres. Fixed-screen shooters of the Space Invaders mold remained popular, with titles such as Galaxians, Galaga and Phoenix successfully building on the formula established in Taito's classic, while developers such as Williams, Konami and Namco experimented with incorporating playfields that were larger than a single screen width in 1980's Defender, 1981's Scramble and 1982's Xevious respectively.

While Defender was a great game that still holds up surprisingly well today, it was Scramble and Xevious that had the most noticeable influence on what we know as shmups today. Scramble was the first game in the genre to incorporate forced scrolling that the player had to keep up with, and also the first in the genre to incorporate a progression of distinct levels. Meanwhile, Xevious is widely credited with popularizing (not inventing - that honor goes to the 1981 Atari game Caverns of Mars) the vertically-scrolling shmup genre, and is also notable for being one of the first games to incorporate more realistic background graphics rather than the abstract, sci-fi settings of its spiritual predecessors.

Throughout the 1980s, widely regarded as the "golden age of arcades," the shmup genre flourished and expanded. Influential classics of the genre that still hold up well today made their first appearances, while developers experimented with different ways of presenting the core shooting gameplay. Some of these were more successful than others - Sega, for example, found great success with the third-person quasi-3D gameplay of 1985's Space Harrier, but its earlier experiment with isometric projection in 1982's Zaxxon failed to leave any lasting impact on the genre.

As time moved on and graphical technology became increasingly impressive, however, the resolutely sprite-based nature of most shmups started to look more and more dated, particularly as 3D polygonal graphics started to become more widespread. It was becoming more and more apparent that the shmup genre needed to evolve in a significant manner if it wanted to compete with the latest flashy 3D efforts that were drawing crowds.

The Birth of Bullet Hell, and the Rise of Cave

And so it was that in 1993, the now-defunct Japanese developer Toaplan unleashed Batsugun onto unsuspecting arcade-goers around the world. Initially appearing to be a fairly conventional vertically-scrolling shooter - albeit one with an interesting RPG-style "level up" system for the player's weapon - it's not until you reach the first boss that you discover Batsugun's hidden secret: bullets. Lots of bullets.

Yes, Batsugun is the first recorded example of what would become danmaku, a Japanese word that literally means "barrage" but which is often translated as "bullet curtain" or "bullet hell." While Batsugun doesn't tend to be credited with actually creating the danmaku subgenre as we know it today, it certainly sets a lot of the modern template in place. After the deceptively straightforward first level, the game starts throwing you increasingly-complex bullet patterns for you to navigate while simultaneously trying to destroy as many enemies as possible. The complexity and oddly beautiful nature of these hypnotic bullet patterns, coupled with the sheer number of them on the screen at once, was intended to be 2D gaming's secret weapon against the impressive, inherently more realistic nature of 3D visuals.

To counter the seemingly-impossible task of avoiding the incoming barrage of bullets, Batsugun adopted an interesting approach to detecting collisions on the player sprite that is still used today: rather than the entire player sprite being sensitive to being hit, only a tiny part of the ship was configured as a "hitbox." Learning where that hitbox was and carefully navigating those few fragile pixels successfully through the hail of plasma death headed your way was key to success in Batsugun, and remains one of the most important aspects of modern danmaku shmups.

Batsugun sadly wasn't enough to save the ailing fortunes of Toaplan, and the company slid into bankruptcy before it was able to release a second revision, known as Batsugun Special Version, into arcades. All was not lost, though, as many refugees from the collapsed Toaplan banded together to form an outfit known as Computer Art Visual Entertainment - better known today in its abbreviated form Cave.

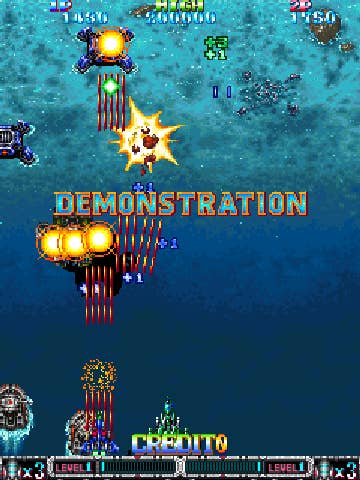

The first fruit of Cave's labors hit the scene some two years after Batsugun's original release. While Batsugun introduced a number of elements that are now de rigueur for the danmaku genre, it was 1995's DonPachi that cemented these features in place and added its own twists on the basic formula to bring us much more in line with what we expect from danmaku titles today. Fun fact: DonPachi literally means "leader bee," but is also, rather charmingly, Japanese onomatopoeia for the sound of gunfire. Imagine, if you will, a Western-developed game called something along the lines of "PewPewPewPewBoom!" - perhaps not altogether implausible in the indie space, but not something you'd expect to see on the shelves of GameStop.

In gameplay terms, DonPachi saw the first implementation of a more complex scoring system than seen in previous shmups. Rather than the destruction of enemies being worth a flat rate, DonPachi features a fighting game-style combo system in which the more enemies you destroy in rapid succession, the more points each is worth. Taking too long to destroy the next enemy breaks the combo and requires the player to build it up again; consequently, the challenge of the game is twofold: firstly, to survive the incoming waves of enemies and bullets, and secondly, to plot out the best possible route that allows you to chain as many enemies as possible into a single combo. This combo system remains intact in even the most recent incarnations of the DonPachi series, and many of Cave's other shooters include even more byzantine scoring mechanics.

That's not all DonPachi introduced, though. To cater to those for whom a single-credit clear of the game was just too easy, DonPachi provided a significantly more difficult "second loop" to play through once the game was cleared -- not only were the bullet patterns denser in this second time around, but enemies also exploded into "suicide bullets" when destroyed. Make it through that second loop and you can truly call yourself a danmaku master. Again, this "suicide bullets" mechanic remains largely unchanged in many of Cave's more recent shmups, most noticeably in Deathsmiles.

The Touhou Project

While Cave is probably the most well-known mainstream developer of danmaku titles, it's far from the only company creating these challenging games - nor is it the most prolific. No, if we're going to talk about sheer number of titles released, it is at this point that we should address the Touhou Project, a series officially recognized by Guinness World Records in 2010 as the "most prolific fan-made shooter series," and one which had its inception around the same time Cave was putting out DonPachi.

The Touhou Project is impressive enough for having run as long as it has - not to mention spawning a variety of works in media other than games - but it's doubly noteworthy for being largely the work of a single individual: one Jun'ya ?ta, better known by his pseudonym ZUN. Dedicated Touhou fans have such respect for ZUN and his work that they gave him an alternative nickname: kannushi, literally "god master," a term normally used to refer to the person responsible for the maintenance of a Shinto shrine, and of leading worship of a given kami, or supernatural being.

Interestingly, ZUN's original intention was not to create the phenomenon he did. Rather, it stemmed from an idle thought in his high school years that there were not many games that focused on miko - traditional Shinto shrine maidens, and a distinctive, recognizable part of Japanese spiritual culture. As a talented musician, ZUN often found himself imagining the music that would go with such games, and headed to college with a mind to compose music for fighting games as his eventual career. However, he quickly came to the conclusion that the best way to get his music into a game was to actually make a game, and thus Touhou - a series based around miko, as he had originally imagined - was born.

ZUN's initial work on the Touhou Project was as part of a team known as Amusement Makers, a game development club at Tokyo Denki University. The group, directed by ZUN, put out five Touhou games for the Japanese PC-98 series of computers, beginning with the Arkanoid-style Highly Responsive to Prayers in 1995 and following up with four danmaku shmups that culminated in 1998's Mystic Square. The first game was largely put together as a programming exercise, while the subsequent titles in the series became shmups due to a combination of factors: the resurgence in popularity of the genre, and ZUN's own love for the gameplay style.

After the release of Mystic Square, it was four more years before the Touhou Project would raise its head again - this time with ZUN working solo as one-man outfit Team Shanghai Alice. The new game was known as The Embodiment of Scarlet Devil and was a significant step forward for the series in numerous ways. Firstly, and most notably, the series had shifted from the PC-98 platform, which was already on the decline when the first five games were released, and had instead made the jump to Windows-based computers. This had a massive effect on the series' popularity - since the PC-98 was largely confined to Japan, the move to Windows meant that many Western players could experience the series for the first time.

The Embodiment of Scarlet Devil was followed up by numerous other games in the series, most of which were the sole work of ZUN, although some - most notably the non-danmaku fighting game spin-offs - were produced in collaboration with fellow Japanese indie developer Twilight Frontier. As the series and its characters grew in popularity, it has since spawned a variety of spin-off products, including music CDs, manga and a huge quantity of fan-produced work, ranging from derivative music compositions to whole other games based on the setting and characters. ZUN himself is supportive of the fan community surrounding his creation and imposes very few restrictions on the work of his fanbase; the only real limit he imposes is that he refuses to allow the series to become commercialized, which perhaps explains why it has never been picked up by a Western publisher and officially brought to North American and Europe.

Ikaruga Brings Bullet Hell West

Numerous danmaku shooters have been released on console over the years, but most have remained confined to their native Japan. One title of particular note that caught the attention of Western gamers was Treasure's 2001 title Ikaruga - a spiritual sequel to the company's earlier title Radiant Silvergun, and originally an arcade machine based on Sega's Dreamcast-powered NAOMI arcade hardware.

Ikaruga took two years to develop - a long time in arcade terms - and was put together by a full-time team of just three people from Treasure, supported by members of upstart developer G.rev. The collaboration came about as the newly-founded G.rev discovered that developing its own arcade shooters was going to cost considerably more than its initial investment capital - consequently, the team took on contract work for both Treasure and Taito, working on Ikaruga and Gradius V respectively. G.rev subsequently brought out its own arcade and Dreamcast shooter Border Down, and later collaborated with Ikaruga director Hiroshi Iuchi on its later original title Strania.

Ikaruga being programmed for NAOMI meant that a home conversion was a snap - the only difference between a NAOMI machine and a Dreamcast was the storage medium used to carry the games. Ikaruga's challenging but fair gameplay and interesting "polarity" twist on the usual formula, allowing you to absorb bullets of the same color as your ship, proved popular in its 2002 Dreamcast incarnation, and made many Westerners aware that the shmup genre - thought by some to have fallen into obscurity - was very much alive and well, thank you very much.

It wouldn't be until the following year that Ikaruga saw an official release in the West; by that time, however, the Dreamcast was on the decline and so the decision was made to port it to Gamecube. For many Western console players, this was their first true introduction to the joys and horrors of danmaku.

And although it didn't sell in vast quantities in either its Dreamcast or Gamecube incarnations, it has a very fond place in the heart of many a shmup fan, and a respected place in gaming culture. It's often noted as being one of the best, most challenging shmups of all time, and anyone who attended the Penny Arcade Expo East in 2011 will have seen two teams throwing down against one another in the game's Trial Mode to determine the winner of the expo's annual Omegathon gaming competition.

If you want to play it today but don't have access to anything that will play either Dreamcast or Gamecube discs, you're in luck - it's available in an enhanced HD format on Xbox Live Arcade right now.

Bullet Hell Today

Danmaku titles are somewhat "evergreen" in their appeal elements, and consequently have a surprisingly long shelf life. As a result, many "new" releases are actually ports of older arcade titles that remain both relevant and fun to play even several years later.

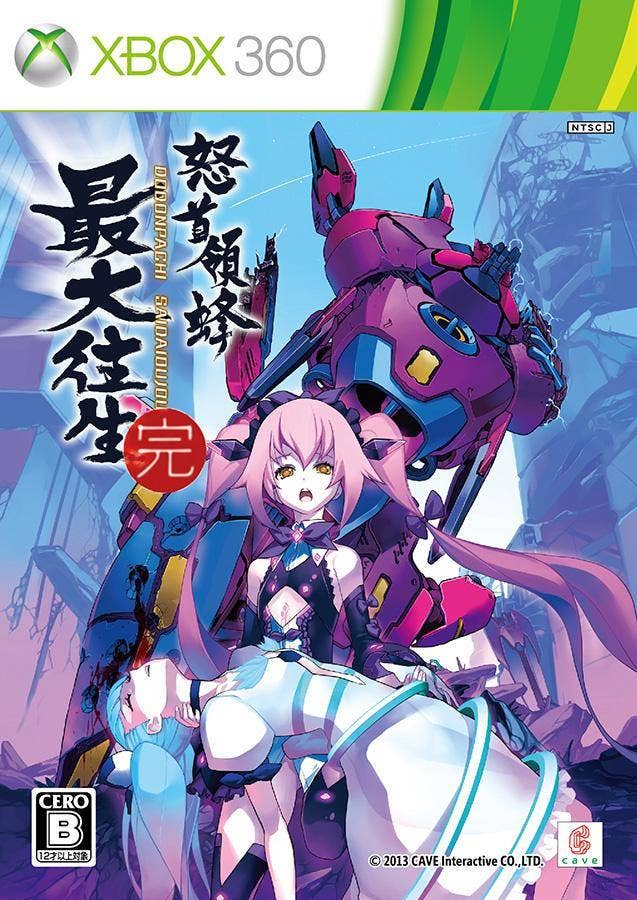

Cave has seen some success with releases of a selection of its arcade hits on the Xbox 360 - a somewhat surprising choice of platform, given Japan's historical reluctance to embrace anything with "Microsoft" printed on it. However, the company has clearly found a passionate enough niche on the 360 to warrant releasing a large number of its more recent efforts, including Espgaluda II; Mushime-sama Futari (aka Bug Princess 2); Deathsmiles and its sequel; DoDonPachi Resurrection (aka DoDonPachi Dai-Fukkatsu); Muchi Muchi Pork and Pink Sweets as a double pack; and Akai Katana Shin.

In a nod to the Western world's enjoyment of danmaku titles, Cave has made a number of its Japan-only releases region-free - including its most recent release DoDonPachi Saidaioujou. Others, like Deathsmiles II, which is available via Games On Demand in North America, remain firmly region-locked in their physical incarnation. It's also worth noting that a number of shmups from other Japanese developers are also region-free, allowing them to be easily imported and played on Western systems - check out Qute's titles Eschatos and Ginga Force, Triangle Service's Shooting Love 10-Shuunen and 5pb's Bullet Soul if your 360 has a hunger for yet more bullets that Cave can't satisfy alone.

Cave has also made bold strides into the mobile market, beginning with iOS ports of Espgaluda II and DoDonPachi Resurrection - both of which include a smartphone-specific game mode with all-new mechanics and original music - and continuing through mobile ports of the Mushihime-sama (Bug Princess) series and Deathsmiles. In 2012, the company released DoDonPachi Maximum, the first of the series to be developed specifically for mobile phones, and initially a Windows Phone exclusive. This has since come to iOS, which it's abundantly clear is Cave's favored mobile platform. Android owners have ports of Espgaluda II and DoDonPachi Resurrection to enjoy, but none of the company's more recent releases at the time of writing.

Cave isn't the only developer working on danmaku titles for mobile platforms, either. A number of other developers realizing that, for once, the touchscreen nature of modern phones and tablets was actually an ideal fit for the fast-paced gameplay of danmaku shmups, have put out high-quality games on both iOS and Android - just do a search for "danmaku" or "bullet hell" on these platforms' respective app stores and you'll have plenty to choose from, from both Eastern and Western development teams - and watch this space for our roundup of ten of the best offerings out there.

With the rise of digital distribution, it has also become much easier to get your hands on independently-developed Japanese titles for home computers, and several publishers have sprung up specifically to bring these games to the West. While the Touhou titles remain somewhat challenging to acquire legal copies of without paying exorbitant import fees, other games such as Platine Dispositif's Gundemonium trilogy and FLAT/Tennen-Sozai's eXceed series are easily acquirable via Steam thanks to specialist publishers like Rockin' Android and Nyu Media. At the same time, established classics of the genre such as Treasure's Radiant Silvergun and Ikaruga have been brought to a whole new modern audience thanks to remastered HD rereleases on Xbox Live Arcade.

As for Western developers, there are relatively few out there willing to tackle this genre of gameplay that Japan has proven itself so adept at, though there are exceptions - most notably Final Form Games' excellent Jamestown, released in 2011. For those new to dodging vast quantities of bullets while trying not to let your increasingly-sweaty hands slip off the controls, Jamestown actually provides a good introduction to the genre with a wide variety of difficulty modes - though be aware that if you want to see the conclusion of the game's surreal Jules Verne-esque story, you'll have to steel yourself and jump into the higher difficulties at some point.

As triple-A games constantly reach for the stars in terms of graphic fidelity and movie-like presentation, it's refreshing to play something like a danmaku shooter as a reminder of a simpler time. While most of them do include some form of rudimentary story, in actuality the main focus of these games is nothing more than demonstrating your skill and dexterity - and, of course, chasing the elusive high score. They're simple to understand, but hard to master - and when everything clicks, allowing you to successfully survive a seemingly-impenetrable barrage completely unscathed, it's one of the most satisfying feelings of elation you'll enjoy in all of gaming. In other words, they are games designed simply for the sheer joy of playing.

As gaming as a medium matures, people are increasingly looking for the "message" individual works have to impart through the combination of their mechanics, story and presentation - and that's great. Just don't forget sometimes - such as in the case of danmaku shmups - that message is quite simply "I'm fun; play me."