Crackdown Revisited: The Game That Launched a Generation

One of the first great games of the last console generation may be one of the first great games of new gen, too. Why Crackdown was ahead of its time.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

When does one decade end and a new one begin? The most obvious and most technical answer, of course, is when the calendar flips and a new number appears in the tens place of the current year. But "decades" as an emotional concept — as units of culture rather than time — don't break down along such hard demarcations.

The human decade doesn't turn with the calendar, but rather with popular trends. For music aficionados, the '60s ended when the Beatles broke up in April 1970. The '80s began early, with the death of disco in July 1979, and ended late, with the September 1991 release of the "Smells Like Teen Spirit" single. For those who mark era by politics, though, maybe the '80s didn't begin until Ronald Reagan was elected, or end until the Gulf War kicked off. For sci-fi buffs, maybe 2001 ushered in the '70s and The Empire Strikes back sent it off. Maybe a fashion fanatic sees the '80s as beginning with the death of bellbottoms or corduroy and ending with hairspray's demise in the face of the hippy-throwback grunge look.

This ambiguity is true of console generations as well. Just because a few companies launch new pieces of hardware doesn't mean video games suddenly experience a transformative renewal overnight. Change happens more slowly, as a more gradual thing, which is why we'll be playing a whole lot of holdovers from last generation this fall. The new generation may have launched last November, but it doesn't truly begin until 2015.

The same felt especially true of the previous generation; even after Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 launched, most of the games they offered felt either clumsy and unfinished or else seemed to be hasty revisions of PlayStation 2-era titles. So what was the game that signaled the arrival of last generation? For some, it may have been Uncharted. For others, Dead Rising. Myself, though, I'd stake my claim on Real-Time Worlds' Crackdown.

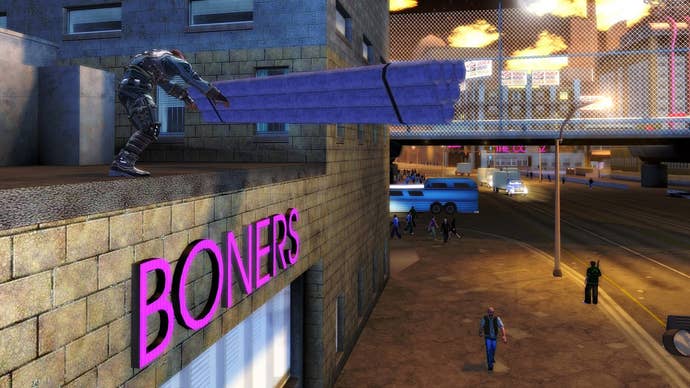

A raucous free-form action game, Crackdown was equal parts shooter, platformer, and open-world adventure. And it felt like nothing anyone had ever played before. Open-world action games weren't unheard of in 2007; on one hand, you had Grand Theft Auto and its myriad clones (e.g. True Crime), while on the other Bethesda's Elder Scrolls games were still trying to strike a balance between immense role-playing freedom and accessibility for the average human being.

Crackdown offered a single, but essential, difference to those other adventures: Its scale. GTA-alikes and free-roaming RPGs presented things from a very human perspective, low to the ground and ultimately constrained by something akin to reality. Crackdown let players feel larger-than-life. Their on-screen avatar, the Agent, began the adventure with superhuman strength, aim, endurance, and skill... and as they collected experience, the Agent only grew stronger. By the end of the game, the Agent has essentially become a superhero, capable of literally leaping buildings in a single bound... and the ones that were too tall for a single bound could still be scaled.

The gravity-defying verticality of Crackdown turned the entire city, not just its streets, into a playground. It was a truly open world, one unbounded by streets and vehicles. You could drive cars, sure, but you could just as easily begin running and take a flying leap for the length of a city block. Cars were just there for style and fun, not for serious play.

Unless you wanted to be serious about cars, in which case Crackdown was totally open to that possibility. It was totally open, period. The player's goal simply amounted to taking down Pacific City's three gang bosses, and in theory you could speed run the game by advancing directly to their lairs and gunning them down. In practice, though, the gang leaders were far too powerful and the Agent initially far too weak to make that work. Instead, the ideal approach was to dismantle their organizations one lieutenant at a time.

Every gang boss commanded a network of underlings, each of whom possessed certain unique traits that enhanced the overall capabilities of the overall group. Take down the guy who ran the chop shop behind the sports arena and suddenly the El Muerto gang drove crappier, less armored cars. Assassinate the guy who headed up Shai Gen's physical training regimen and suddenly that gang's soldiers would have weaker constitutions. The more underlings you took out, the more easily you could take on the high-level crime lords.

There was no prescribed order to the gang commanders in Crackdown, or even to the gangs. While the path of less resistance was to go after the Latino stereotypes followed by the Russian stereotypes followed by the Asian stereotypes — Crackdown was not exactly a bastion of sensitivity, unfortunately, and Real-Time Worlds refused to include female avatars for production resource reasons years before Ubisoft trotted out that line of reasoning — you didn't have to go that route.

In fact, you didn't even have to mess with the bosses at all, if you didn't want. Crackdown's story objectives became almost secondary for most people to the fact that the game presented an absolutely ludicrous playground to mess around in. The combination of the Agent's physical prowess and a "next-gen" physics system turned the entirety of Pacific City into a plaything. You could jump around from building to building, drive around by way of the well-planned and highly effective freeway system, swim from shore to shore, or mess around with unique elements of the sandbox. The crates at the docks that you could topple with grenades or toss with abandon, perhaps. Or how about the unique globe sculpture near one of the Shai Gen's bases that you could treat like a massive toy, like something from Fight Club, but which would never respawn once uprooted?

Really, though, Crackdown's biggest innovation came in the form of its multiplayer mechanics. There was no deathmatch in Crackdown, no player-versus-player or capture the flag or king of the hill. In keeping with the spirit of the adventure, there was simply open-ended online cooperative play. Two Agents could team up via Xbox Live to tear apart the host's city. They could work together to stop the crime lords, work separately to divide and conquer, or say "the hell with that" and just goof around together. While simplistic, the coop style was absolutely unprecedented among console games — a totally open world that two friends could experience together, on their own terms.

Even alone, Pacific City managed to offer manic fun, thanks in large part to its brilliant handling of the collectathon concept. Like its inspiration, Grand Theft Auto, Crackdown gave players a ludicrous number of random things to pick up throughout Pacific City. But it turned collecting into an addictive game in and of itself, not simply a grind or a distraction or an afterthought. Players gained legitimate benefits from gathering the green and blue orbs littering the environment — experience gains for their Agent's stats — and the orbs themselves taunted players. They glowed, causing them to be visible from a distance, and they hummed, meaning that you always knew when you were near an orb, even if you couldn't see it.

The orbs often sat on obvious high points atop buildings or other structures, inviting you to scale the city heights and make use of the Agent's dexterity... and quite often sitting well out of reach until you gained more jumping and climbing power. More than a pause screen "percentage complete" statistic, Crackdown's orbs fit organically into its play mechanics by giving you incentive to collect them, to pursue them, and to aspire to reach greater heights in the game.

The game's Grand Theft Auto connections weren't incidental; Crackdown's director was David Jones, the former DMA Design/Rockstar North designer responsible for Lemmings and, yes, GTA. It's no coincidence that the game he created after leaving Rockstar resembled GTA on such a fundamental level; yet at the same time, it felt wildly different as well, freeing itself of the crime movie pastiche that the Houser brothers defined GTA as. With its comic book visuals and mechanics, Crackdown was much less about retelling its creators' favorite movies and more about giving players the freedom to fight crime in a big city at their leisure. It's no accident that the game's main DLC add-on was called "Keys to the City" — at heart, Crackdown was about player empowerment and expression in a way that wouldn't be topped until Minecraft came along. And Saints Row IV.

By no means was Crackdown perfect, though. Even at the time, its mission structure came off as rather slight in comparison to other open-world games. Despite allowing players to control an Agent of any ethnicity, its handling of race with the gangs was troubling, to say the least. And in hindsight, its place as the bellwether for a generation shines through in its overall roughness. Its visual style makes the game appear to be a scaled-up Xbox title — though certainly the Xbox couldn't have handled the massive, seamless world of Pacific City, the simple structures and repetitive textures of the environments look decidedly dated. And the controls feel just plain weird; the past seven years have seen the codification of rules and layouts for controllers, and Crackdown came into being in a time before that standardization. X to swap weapons? LB to reload? Down on the D-pad to switch to sniper view!? What madness is this?

On the other hand, certain elements of Crackdown were well ahead of their time. Open-world cooperative play is something that the rest of the industry is only now getting around to exploring. Seven years after Crackdown's debut, its biggest innovation was the most common theme at E3 2014. And while its story was slight, Crackdown nevertheless seems a prescient look at its own future, casting players as participants in a straight-faced satire of a hellish Orwellian world ruled by militarized police. In light of all that's happened in the world since 2007 — the suppression of the Occupy movement, the rise of the surveillance state, the advent of drones, and more — Crackdown actually manages to be more timely today than it was at its debut.

That's why I'm so excited for the recently announced Crackdown reboot; I'd love to revisit this experience with the shine and polish applied by all the games that followed in Crackdown's footsteps. While I'm hoping for a new layout for Pacific City (given that the game's "sequel," Crackdown 2, amounted to nothing more than a zombie mod for the first game), I'll still play it and very likely love it no matter what form it takes. Now that the entire industry is finally getting around to ripping off what made Crackdown so great, it's only fitting that the game that kicked off the last console generation return to lead the way for the next gen.

Watch: Our Crackdown Revisited video companion piece.