Burnout Paradise 10th Anniversary: Remembering Criterion's Race Towards the Future as it Heads to PS4 and Xbox One

A decade ago, Burnout Paradise went in a radical new direction. We remember Criterion's classic racer on its 10th anniversary.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"Take me down to the paradise city / where the grass is green and the girls are pretty."

The opening riff from "Paradise City" still reverberates in my head to this day. Even now it conjures images of explosive crashes and hard-fought races. I'm not even much of a Guns N' Roses fan, but I still find myself humming it from time to time, if only because it was so ubiquitous in Burnout Paradise.

Like the song that accompanies it, Criterion's pioneering racer remains seared into my memory. Every open world racing game I've purchased since—from Need for Speed to Forza Horizon 3—has been an attempt to recapture the pure joy of Burnout Paradise. Nothing has quite been able to replicate it.

Old-school fans still consider Burnout 3 to be the apex of the series, but I've never been what you would call a racing fan. Car culture is about as foreign to me as my sports fandom is to the rest of the USgamer team. Before Burnout Paradise, my favorite racing game was Mario Kart 64.

Like many other games of that period, I downloaded Burnout Paradise on a whim. Flush with cash from my first freelance gig and thrilled to finally have an HD console—I didn't get a PS3 until 2009—I wanted to play a real "showcase game." And that's exactly what I got.

It's easy to forget now what a shock to the system games like Burnout Paradise were back in 2008. The previous generation wasn't exactly ugly, but the leap to high-definition put even the likes of God of War and Metal Gear Solid 3 to shame. What followed was a mini-renaissance for game development. The two year period of 2007 and 2008 alone gave us Burnout Paradise, BioShock, Fallout 3, Call of Duty 4, Uncharted, Portal, Left 4 Dead, Dead Space, Far Cry 2, Braid, and Mirror's Edge. It was a remarkable period that helped define much of gaming as we know it today.

Burnout Paradise was especially notable for the way it brought many of the era's prevailing trends under a single umbrella. Its open world foreshadowed the "open everything" design that would come to dominate the following generation. Its seamless online design heralded the "always online" platforms that would follow. Even its massive DLC packs, coming a mere two years after Oblivion's horse armor flap, felt like the wave of the future.

Like most trailblazers, it also suffered its share of controversy. Plenty of old-school racing fans took umbrage at the notion of an open-world driving sim. They complained about the inability to restart races, the need to go to the body shop for repairs, and the lack of structure in the "free driving" portion of the game. The demo was controversial enough that Criterion publicly responded to criticism with a post that's since been lost to the tides of the Internet. Ars Technica complained in response:

Give me my Burnout back! I loved it because the "linear and limited" experience made Crash mode almost like a puzzle game. Everything you've been saying in your defense is just convincing me that this isn't what I'm looking for in a Burnout game. As you're trying to sell me on it, all I hear is, "See, we've taken away what you've liked, and added a lot of what you don't like. But you should still buy it even if you don't like the demo, because there is a WHOLE LOT of what you don't like in it, and we've worked hard to make the largest amount of things that aren't like Burnout to put in there."

Ars Technica's complaints were echoed in forums and blogs around the Internet. Even today, there are fans who just want the old Burnout back. As the old adage goes, "It was different, and therefore it sucked."

When Burnout Paradise finally launched a few weeks later, Ars Technica walked back their criticism with a glowing review:

"I blame much of the bellyaching about the game on the demo: it's too large for what people expected from Burnout and too small for what the final game delivers. When you play the final version with the entire city and spend a few hours getting your bearings, you'll see that the changes made to the game play and the new direction the series is going in is a positive one. Add in one of the better online racing systems in recent memory, and you have a very compelling $60 purchase."

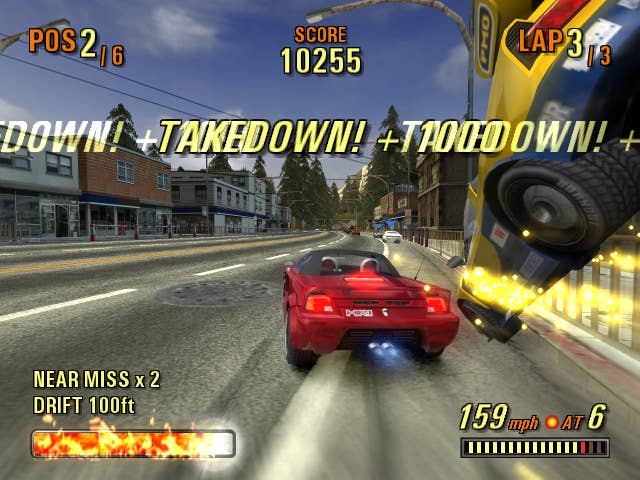

I wasn't aware of this controversy. I just remember the first time I pulled out of the gas station with Guns N' Roses blaring, an entire island with events and races at my fingertips. I remember how shiny and detailed the cars looked in HD. And I remember the crashes. Oh boy, do I remember the crashes.

Burnout Paradise's crashes were works of art. When you hit a car just right, it would go spinning away in a whirlwind of exploding metal. The same could happen to you as well; and for as frustrating as it could be to lose a white-knuckle race in the very last second, it was still a sight to behold.

Half the fun of Burnout Paradise was driving around and knocking as many cars as possible off the road. It's an element that's sorely missed in Forza Horizon 3—the tradeoff of having reams of licensed cars. Head-on collisions just feel wrong when both cars fail to explode in slow-motion glory.

The collisions made Burnout Paradise's island a high-speed bumper car arena. I'd be driving along a picturesque coastline at Warp 9 and suddenly bam, I'd be exploding. It made the island feel somehow more grounded, more real. It was the video game equivalent of a Michael Bay film, but actually being able to destroy my car felt good.

When I wasn't blowing up my car, I was hunting for billboards. Burnout Paradise brought an interesting layer of environmental puzzle-solving to the table—something you don't typically see in other racing games. It would challenge you to try and figure out just what route you needed to take to reach collectibles. If you hit it, you would be rewarded with a satisfying thwack as it exploded around you.

Stunts featured a different sort of environmental puzzle solving. Stunt runs were all about finding the perfect straight line course loaded with jumps and corkscrews. It was exhilirating to hit everything just so while boosting as hard as possible, the score multipliers exploding as the world ripped past you. The races were fun, but the search for the perfect stunt run was what kept me up at night.

In hindsight, Burnout Paradise was loaded with an astounding number of things to do—a hint of the online platform-oriented development to come. You could look for billboards to break, stunts to undertake, mini-speed records to break. Burnout Paradise kept you constantly informed of your friends' place on the leaderboards, and encouraged you to challenge them. In a era when online console game was only really beginning to truly blossom, this was revolutionary.

Criterion even went so far as to seamlessly integrate an online world populated with other players, which you could switch to at any time. Burnout Paradise felt like the platonic ideal of what a "next-gen game" should feel like back in 2008. It had everything: full online integration, clever leaderboards, massive DLC. While other publishers were still figuring out what gamers wanted, Burnout Paradise was dropping huge updates like Big Surf Island, which introduced an entirely new island to explore. Its online integration was so complete that Criterion was even able to sell ad space to eventual president of the United States, Barack Obama.

You could argue that this trend was not altogether good. Plenty of publishers took Burnout Paradise's ideas and abused them, larding up their games with preorder DLC and leaning hard on grinding for long-term appeal. If Burnout Paradise came out today, it would most definitely have loot boxes.

But when it came out, Burnout Paradise felt fresh and new. It felt like the future of gaming. And that's because it was.

Burnout Paradise in Hindsight

A decade after its original release, some of the shine has obviously come off Burnout Paradise. The textures don't stand out as much, the lighting isn't as vibrant. It's no longer the graphical and technical showcase that it once was.

Nevertheless, it still stands out in my memory as the ideal of open world arcade racing. I've been chasing the high I got from Burnout Paradise for a decade now, and every time I've thought to myself, "It's just not the same."

Criterion's Need for Speed games muddled the pleasure of free driving with cops. Forza Horizon traded the joy of stunts and crashes for more realistic physics and a much stronger focus on straight-up racing. I love Forza Horizon 3, but there is a Burnout Paradise-sized hole in my heart that hasn't been filled in a very long time.

The team that built the original Burnout Paradise is long gone. Burnout Paradise director Alex Ward left Criterion in 2013 to start his own studio. Criterion hasn't made a game of their own since.

There have been rumors abound that Burnout Paradise will be remastered in the very near future, which will be great for anyone who missed it the first time. But otherwise, the Burnout franchise is dead. EA's focus is entirely on Need for Speed these days. Even if it returns at some point, it won't be the same.

But Forza Horizon has shown that there's still very much a future for open world racers; and if someone wants to try their hand at the genre, the blueprint is there. Burnout Paradise may be long gone, but its legacy is relevant as ever.