Borderlands has a problem with dwarfism and disability

Discounting Claptrap’s metal visage, Sir Hammerlock is the first friendly face you meet in Borderlands 2.

The last survivor of Liar's Berg, surrounded by frozen wasteland, he’s dressed from head to toe in Victoriana and sports a deeply unconvincing accent. He is the series’ comedy Brit and researcher of local phenomena - a role he fulfils by sending you out on expeditions to document and destroy.

One of the first is an optional mission to seek out Midge-Mong, a local bandit with dwarfism who rides on the back of a bullymong - a four-armed, ape-like creature from Borderlands lore.

“Ah, what an unlikely symbiotic relationship, two deadly creatures cooperating to survive this harsh environment,” says Hammerlock, cheerily. “Also, the midget looks like a little human backpack, and that’s funny.”

Though rarely expressed so explicitly as this, dwarfism is a consistent target for comedy throughout Borderlands 2. Players frequently come into contact with enemies labelled Midgets, who speak in pitched-up screams. Sometimes they’re carried piggyback-style on the shoulders of their larger comrades. It’s made clear that dwarfs are considered inherently funny, a spectacle to add to the sense of strangeness on Pandora’s alien surface.

There’s an in-game explanation for their existence. Back before the events of the first Borderlands, miners found a vault key fragment while digging, and its discovery altered the workers - sending many insane and physically mutating others. That lore, however, doesn’t help the real-life dwarfs who live with the consequences of depictions like this.

Peter Dinklage has described jokes about dwarfism as “one of the last bastions of acceptable prejudice”. A 2010 study conducted by the University of East Anglia found that 80% of people with dwarfism had received verbal abuse, and that 12% had suffered violence. Making them subjects of video game violence, I imagine, doesn’t help - and I’m yet to find a dwarf in any Borderlands who isn’t designated an enemy.

“Ours is a society in which people are drip-fed - through history, media, literature, and popular culture - the idea that dwarfism is, at best, undesirable, and, at worst, to be ridiculed or feared,” dwarfism activist Eugene Grant wrote in a Shortlist column last year. “Most average height people meet and get to know few, if any, dwarf people in real life. So cultural representations matter a great deal and massively influence perceptions, shape attitudes, and inform behaviour.”

Borderlands joins a long line of representations of dwarfs as either punchlines, as in Austin Powers, or curiosities, like the Oompa Loompas of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The term midget is in itself considered derogatory, associated with the freak shows of PT Barnum and the public display of dwarfs for novelty entertainment. Unsurprisingly, when Little People of America surveyed its members, over 90% said they never wanted to be referred to that way.

This isn’t a history Borderlands’ developers are completely unacquainted with. By The Pre-Sequel, Midgets had become Lil’ Scavs, and in Borderlands 3 they’re called Tinks. Producer Chris Brock acknowledged in a PCGamesN interview that the original name had not been “super sensitive” - yet Randy Pitchford has tweeted that the change is “not a censorship thing”, but rather down to a fun title the team came up with during development. It’s an interesting choice of words, using “censorship” there. The fact that Gearbox seems aware of the offense it might cause only makes the fundamental problem - that Tinks exist as enemies at all - more exasperating.

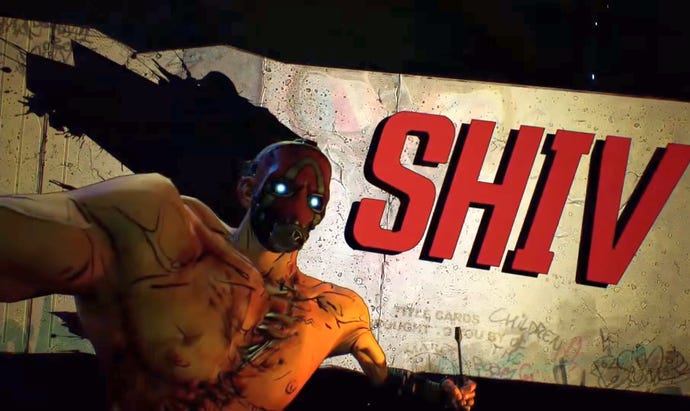

To make matters worse, Borderlands 3 evidently has a wider problem with its presentation of disability. The very first mini boss you face, Shiv, has hand and arm deformities. It would be a different matter if similar disabilities were presented among your allies, but instead they seem exclusive to the Children of the Vault - the same bandit faction many of the Tinks belong to.

Friendly NPCs in Borderlands 3 frequently sports prosthetics. But they’re either voluntary, like that of Atlas CEO Rhys Strongfork, who replaced his arm to get ahead in Hyperion’s data-mining department, or part of a cool backstory, like Hammerlock’s encounter with a thresher named Old Slappy. There’s a clear divide between the heroic disabilities that result in robotic eyes or steampunk limbs, and the bandit ones that leave their sufferers with impairments. Those who grow up with real-world disfigurement often feel as if they’re left outside society; to mirror that situation within the fantasy fiction of Borderlands feels both unnecessary and unthinking.

Earlier this year, Rage 2 was criticised for using birth defects - specifically cleft lips and palates - as shorthand for subhuman enemies. id Software’s Tim Willits was apologetic, if taken aback, when questioned about the decision by Polygon’s Chris Plante, but the game launched without any obvious concessions. In that context, Borderlands 3 appears to be part of a wider industry issue in the representation of disability - particularly when it comes to designing enemies meant to evoke disgust, fear, or laughter. It’s time for shooter developers to reexamine how they pick their targets, and who they might be dehumanising in the process.