Blast from the Past: The Dawn of the First-Person Shooter

With several remakes of classic 1990s first-person shooters on the horizon, Pete kicks off a detailed exploration of this most prolific of game types with an exploration of the genre's genesis.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The 1990s played host to some of the biggest technological advancements in gaming history, and many of them were centered around the fledgling first-person shooter genre.

It was an exciting time to be a gamer, for sure, and while new first-person shooters are often greeted with cynicism today, it's worth remembering a time when this particular style of gameplay was pioneering the use of many technologies and mechanics that we take for granted today.

It's also worth looking back at this particularly exciting period in the medium's history as a number of remakes and reboots prepare themselves for launch: in the next couple of months, we've got new takes on Apogee's Rise of the Triad and 3D Realms' Shadow Warrior inbound, along with recent news that Duke Nukem Forever's final developer Gearbox stymied attempts to provide a similar modernized take on Duke Nukem 3D.

Get Psyched!

There's some debate over exactly what the first ever first-person perspective video game was, but it's either Maze War, an early example of a maze-based "deathmatch," and a game which pioneered the "flick-screen" grid-based movement that would be seen in classic dungeon crawlers such as Wizardry and Eye of the Beholder for many years afterwards; or Spasim, a space combat game which purports to be the first ever 3D multiplayer title.

Both games, which came out in the mid-1970s, were extremely primitive by modern standards, but they are both noteworthy for the fact they focused on the "playing together" aspect that remains popular in the first-person shooter genre today. The idea of pitting the player against computer-controlled opponents is something that would not enter the common language of gaming until a little later once programmers started to get their heads around the idea of artificial intelligence -- or at least primitive means of making in-game characters behave independently of player input.

Both Maze War and Spasim passed the general public by to a certain degree, though, due to a couple of important factors: firstly, in the 1970s, computers tended to be large, bulky machines confined to dedicated business or academic premises rather than the self-contained devices most people have in their homes today; secondly, both games were designed for said proprietary systems -- NASA's Imlac PDS-1 systems in the case of Maze War; the networked academic system PLATO in the case of Spasim.

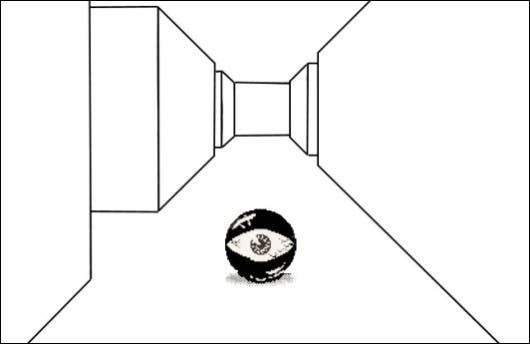

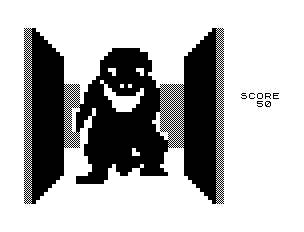

It wouldn't be until 1982 that players at home would be able to explore a computerized first-person perspective environment on a relatively standardized piece of hardware for themselves. 3D Monster Maze for the Sinclair ZX81 was a revelation at the time; rather than the blocky, unrealistic, 2D visuals of other early computer games, 3D Monster Maze provided an environment that people could relate to reality -- and one of the most terrifying adversaries in all of gaming history: the fearsome T-Rex.

3D Monster Maze was a game you couldn't win; you could just lose less badly than a previous attempt. The T-Rex would always get you in the end, and there was no escape; you simply had to survive as long as possible, with each step you took earning you points. Escaping one maze would simply throw you into another, and as the game's pace gradually increased over time, it got more and more difficult to remain rational and keep track of where you'd been. It was a surprisingly exciting experience, despite its primitive presentation, and remains popular to this day.

Beyond 3D Monster Maze, a few developers experimented with various implementations of the first-person perspective and 3D graphics over time. Two of the progenitors of the open-world style of gameplay -- Alternate Reality and Mercenary -- each had their own contributions to make: Alternate Reality introduced texture-mapped 3D graphics, which wouldn't become widespread until many years later, while Mercenary was one of the earliest first-person perspective games to eschew the grid-based movement of many of its peers and allow complete freedom of movement in three dimensions. Elsewhere, series such as Richard Garriott's long-running Ultima series experimented with the use of first-person perspective 3D visuals when exploring dungeons in its early installments.

Old-timer Maze War had a surprisingly enduring legacy, though, with ports to a variety of different platforms over the years. Eventually, 1987 saw a spiritual successor appear for home computers in the form of MIDI Maze -- a game named for its use of the 16-bit Atari ST's MIDI ports to facilitate networked gameplay. MIDI is more commonly used to connect musical instruments such as keyboards to computers -- the acronym stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface, after all -- but MIDI Maze's developers found that the interface's ability to send and receive data was ideal for allowing several different computers to play in a shared game space.

MIDI Maze is regarded by many as the progenitor of what we know as "deathmatch" these days thanks to its freedom of movement, competitive gameplay and customizable nature. It even spawned a port (rebranded Faceball 2000) to the original Game Boy, where it was the only title for Nintendo's handheld to support up to 16 simultaneous players.

As the '80s slowly and inexorably crept towards the '90s, 3D gameplay started to become more and more widespread as developers became more and more adventurous. We saw the birth of the cross-platform 3D engine in the form of Incentive Software's Freescape, which went on to power eight different games across six different platforms. We saw outfits such as Jez San's Argonaut Software -- who would later go on to develop Star Fox for Nintendo -- pushing the boundaries of what was possible on the 16-bit platforms of the time. We saw Mercenary developer Novagen Software go from modeling a single city to an entire solar system.

And then in the early '90s, everybody suddenly started paying very close attention to PC gaming.

Into the Abyss

In 1992, Origin Systems, publisher of the popular Ultima series of PC role-playing games, released Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss -- the work of Blue Sky Productions, who later became Looking Glass Studios. It's not an exaggeration to say that the game was revolutionary, and well ahead of its time.

While first-person perspective role-playing games weren't anything new even in 1992, they'd all followed the grid-based movement and 90-degree turns approach that had been around since Maze War. What Ultima Underworld offered for the first time was complete freedom of movement in a fully three-dimensional environment -- players could walk, run, jump, climb stairs, climb slopes, fall off high places, swim and even look up and down -- the latter facility being something that wasn't at all widespread in other first-person games until much later.

Ultima Underworld's engine allowed for a number of elements that had never been seen in games prior to this point -- texture-mapped walls, floors and ceilings; tiles at multiple heights to create platforms, cliffs and stairs; sloped surfaces; and walls at 45-degree angles. These things may sound laughable to us today, but when you consider that even other first-person games around at the time were still using grid-based maps with walls, floors and ceilings that were all the same height, it's hopefully apparent that Underworld's three-dimensional environment was really something special.

Not only was the tech impressive, but there was a great game in there, too; rather than being a straightforward dungeon crawl or hack-and-slash action adventure, Ultima Underworld had a plot and simulation elements that rivalled any of its 2D predecessors. There were generally multiple ways to approach each situation the game confronted you with, and this particular aspect of gameplay went on to be a strong influence on Warren Spector -- who worked for publisher Origin at the time and was rather jealous to not be selected as producer on the Underworld project. Spector, of course, went on to create BioShock's precursor System Shock and Deus Ex, both of which were influenced heavily by Underworld's legacy.

Ultima Underworld proved to be a critical success, but sales started slow. Word of mouth gradually spread, though, and the game eventually sold in excess of 500,000 copies -- a small number by today's standards, but a smash hit back in the early '90s.

Achtung Baby

Meanwhile, a little-known outfit called Id Software had been quietly working on first-person perspective games since the early 1990s. 1991 saw the first fruits of their labors in the form of Hovertank 3D, a game which combined flat-shaded cube-shaped walls with sprite-based enemies that moved smoothly around a 3D space to provide a convincing simulation of actually being in the environment. While not significantly more advanced than earlier 16-bit titles such as MIDI Maze in terms of capabilities, Hovertank 3D's engine was noticeably faster, smoother and more efficient than almost anything on the market at the time.

Hovertank was followed up in short order by Catacomb 3-D, which was the third installment in a fantasy-themed series Id had been working on since 1989. The first two Catacomb games had unfolded from a top-down perspective, but Catacomb 3-D wowed everyone who played it with its first-person perspective and texture-mapped walls. Catacomb 3-D was also the first game of its type to depict the player's hand (or, more commonly these days, weapon) in the player's viewport, which helped facilitate accurate aiming.

It was 1992's Wolfenstein 3D that put Id Software on the map for many people, though. Hitting the market a couple of months after Origin's Ultima Underworld, its 256-color VGA graphics (Catacomb 3-D had only used the PC's 16-color EGA mode), digital sound effects and vast amount of content not only established now-recognizable names such as John Romero, John Carmack and Tom Hall as forces to be reckoned with, but was also the first game on PC that simply wasn't possible on any other platform available at the time. The 16-bit Commodore Amiga and Atari ST home computers just didn't have the processing horsepower or graphical capabilities to handle something as complex as Wolfenstein, and of the home consoles available at the time -- the Sega Genesis and Nintendo's Super NES -- only the SNES' Mode 7 scaling and rotation technology brought it close to being able to handle the things that Wolfenstein was doing.

Wolfenstein's engine may have had fewer capabilities than Ultima Underworld -- it was still projecting a 2D map into "fake 3D" space rather than providing a fully 3D environment such as that seen in Origin's title -- but it was faster and more efficient. While Underworld's 3D window was only a relatively small proportion of the screen, Wolfenstein's almost filled the player's monitor; while Underworld's texture maps bent and warped when viewed from certain angles, Wolfenstein's graphics stayed rock solid however you looked at them.

As for the game itself, Wolfenstein 3D set the template for many of the first-person shooters that followed in the years immediately afterwards. Released under the "shareware" business model, whereby a significant chunk of the game was available for free, with the rest available to paying customers, the original PC version of Wolfenstein unfolded across six episodes of nine levels each. In each level, the player simply had to make their way from the level's entrance to the exit, trying not to get killed along the way. If you knew the route, it was possible to complete each level in a minute or less; if, on the other hand, you wanted to seek out and kill every enemy, find every treasure item and locate every secret wall, you'd be spending a bit longer on each floor. Beating the "par" time for a level, killing all the enemies, finding all the treasure and finding all the secrets rewarded the player with bonus points -- yes, this was back in the days when games still had scores, even when it wasn't altogether necessary.

Each episode concluded with a boss fight against an extremely powerful enemy. The six episodes were split into two story arcs -- the first three followed the protagonist B.J. Blazkowicz as he escaped from the titular castle and proceeded to take his revenge on the Nazis, culminating in a showdown with Hitler in a robot suit (yes, really) at the end of the third episode; the second three acted as a prequel, in which Blazkowicz was sent in to deal with a fictional Nazi chemical weapons plot. The plot didn't matter a jot in terms of gameplay, of course -- some might say nothing has changed in the genre since -- it simply provided a degree of context for all the killing.

The original PC version of Wolfenstein offered four different weapons -- a knife for melee attacks, a pistol, a machine gun and a chaingun. All weapons -- except the knife, obviously -- made use of the same ammunition, which could be acquired either from downed enemies or found lying around the levels. Generally speaking, once you'd found the chaingun, there was really no reason to switch back to the other guns, unless you wanted to conserve ammunition. The idea of weapons having distinctive characteristics and unique "uses" was something that wouldn't come until a little later in the genre's development.

Wolfenstein was from the days prior to regenerating health, too, so taking damage was permanent -- or at least until you found a healing item. Taking cues from old-school computer and console games, health could be restored by eating plates of food left scattered around the various levels, or by collecting first-aid packs. In a somewhat gross twist, dropping below 10% health also allowed you to restore your vitality 1% at a time by drinking bloodstains from the floor.

Wolfenstein 3D was certainly the most influential first-person shooter of this period by a long shot, but what of its successors?

Don't Let Goldfire Catch You in Here!

Wolfenstein 3D's success prompted a large number of developers to try their hand at similar first-person perspective titles. Many of these were relatively unimaginative spinoffs, perhaps trading the World War II setting for sci-fi (Corridor 7) or a more family-friendly setting (early Epic game Ken's Labyrinth). Even Id churned out an uninspiring sequel to Wolfenstein in the form of Spear of Destiny, which replaced the original's episodic structure with a linear progression and introduced a few new enemies but was otherwise almost identical.

One particular title of this era stands out as genuinely pushing the genre forward in several ways, however, and that was Jam Productions' Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold, which hit the market through publisher Apogee in 1993.

Running off a modified version of Wolfenstein 3D's engine, Blake Stone provided a number of interesting twists on the basic Wolfenstein 3D formula. While still released as shareware and split into discrete episodes, Blake Stone allowed non-linear progression between levels -- once you had completed one, you could later return to it and collect things you might have missed earlier, and indeed in some cases you needed to trigger switches on other floors in order to progress further on your current one.

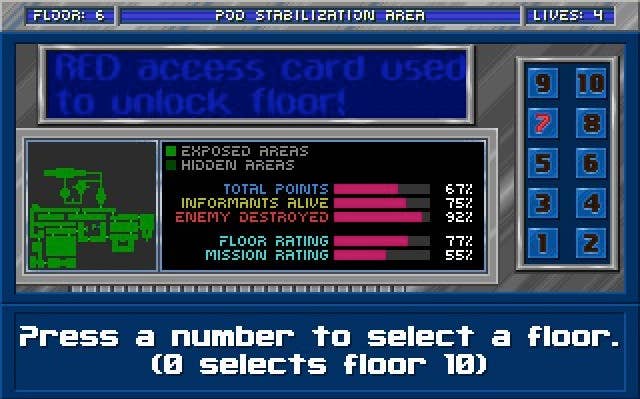

Blake Stone also introduced textured floors and ceilings to the engine, which immediately made things look much more realistic than Wolfenstein's walls floating in space, as well as helpful additions to gameplay such as an automap and real-time stat tracking. Automaps had been seen in prior games, sure -- Ultima Underworld was one -- but Blake Stone's was the first implementation of such a system in a first-person shooter, and due to the maze-like nature of many of the levels, it quickly became a godsend.

While the basic formula was similar to Wolfenstein 3D, there were a few interesting twists, too. Now, rather than simply having to find the path to the exit to progress to the next level, Blake Stone demanded that you find a red keycard somewhere in the level, then make it back to the central elevator that connected all floors. Finding the keycard was generally fairly easy and you could easily romp through the levels very quickly if that's all you were going for. That real-time stat tracking in the automap screen encouraged you to seek out hidden enemies and treasure items, though -- a percentage-based "floor rating" constantly taunted you, making you feel that if you just spent a little longer looking for secret rooms, you'd have the satisfaction of knowing that you'd cleared that floor completely.

Of course, the game designers knew player psychology very well, and often made these secret areas fraught with danger -- hidden enemies, respawning enemy generators, traps, confusing mazes -- but the game was rewarding and enjoyable to a wide variety of players as a result. Completionists could enjoy the feeling of increasing their "mission rating" ever onwards towards 100%; those who simply wanted to blast their way through could make it through the whole game much more quickly.

Blake Stone played with players' expectations in other ways, too, by introducing interactive elements around the levels. Food units would dispense food and beverages to heal the player, for example, while certain scientist characters wandering around the levels were designated as friendly informants rather than enemies, and would provide Stone with helpful items and advice when interacted with -- as well as a scolding message if you killed them. Just to throw a further wrench into the works, however, not all of the scientist characters were sympathetic to Blake; some of them genuinely were enemies, meaning players had to be genuinely careful who and what they were shooting at at all times.

Despite all these great new additions to the first-person shooter formula, however, Blake Stone didn't sell particularly well. The reason? A mere week after its release, Id Software made a triumphant comeback with a little game called Doom that you might have heard of.

But that, as they say, is a story for another day.