BioShock Infinite: America's Fairground

Chris Donlan goes in search of Columbia's origins.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

SPOILER WARNING: Do not read this piece until you've finished playing BioShock Infinite.

George Washington's all over BioShock Infinite. From the gold bust you see in the stairwell of the game's opening location to the mechanized killers who chase you through later levels, chattering out sound-bites as they shoot, Irrational has a lot of fun with the weird iconic pliability of this particular founding father. By and large, though, Washington seems to be employed as a symbol of America's grand contradictions - contradictions that have been exaggerated on the fantastical floating streets of Columbia, but which have very obvious origins back on the ground.

Along with the likes of Franklin and Jefferson, Washington was founding a country based on the tenet of individual freedom while simultaneously owning slaves. This is one of the main reasons, presumably, why this fated trio are turned into angels by the racist prophet Comstock, while one of their eventual successors, Lincoln the abolitionist, is depicted as a spindly devil who led America astray. Speaking of devils and angels, Washington is also used to explore one of the game's deeper retconnings of history: what would America look like if its early government hadn't separated church and state, but had sought to truly blend them? Why not have Father Washington? Why not give him vast wings, a tablet bearing the ten commandments, and a glowing sword? Why not motorize him - this is the 20th century after all - and turn him into a holy Terminator?

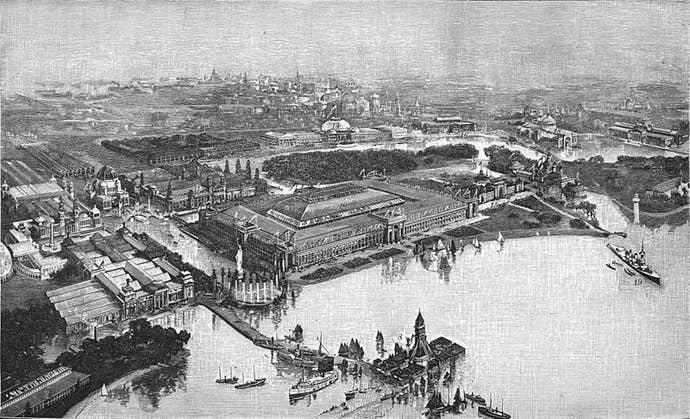

Technology, patriotism, history and progress: the founding fathers are a focal point for many of Infinite's preoccupations, but the thing that truly draws these elements together - and gives the great men a landscape to haunt - is Columbia itself. Columbia and, perhaps more illuminatingly, Columbia's biggest real-world inspiration: the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.

The 1893 World's Fair is one of the defining moments in US history - an exposition so significant that its memory has endured for over a century, long after the candy floss has fossilized and the stucco buildings have been eaten away by the elements. The fair had such an impact because it arrived at a time when the nation was feeling dangerously upbeat about things, and it then took America's approach to progress and showed it to the rest of the world. It too motorised Washington, in a manner of speaking. It just chose not to give him a machine gun.

The fair, like Columbia, was both a truly massive undertaking and a subject of great fascination. It was also a curious blend of the old and the new - of Beaux-Arts architecture with its elegant ties to past traditions, lit by electric lamps and filled with futuristic treats. Cracker Jacks, automated dishwashers and Shredded Wheat all had debuts in Chicago, while the skyline was dominated by the world's first Ferris Wheel - a real beast containing 40 seats in each of its cars. Like Columbia, the fair was a marvel of engineering, built to a crazy deadline and in an unlikely location, using a handful of new techniques. And, like Columbia, it was a symbol as much as a little city - a bright thing on the horizon, positioned to catch the nation's eye and focus its spirit, to remind it that greatness awaited.

Greatness would come at a cost, however. In The Devil in the White City, Erik Larson's book about the fair - it's one of BioShock creative director Ken Levine's favourites, and a key source for the creation of Infinite - the author intercuts the grandiose tale of the exposition's construction and America's arrival on the world stage with the machinations of Dr H. H. Holmes, the country's first serial killer.

Holmes preyed on the human traffic lured to Chicago by the fair, constructing a rather distressing hotel composed of windowless rooms that could be filled with gas as his whim dictated. (I believe some motel owners have since run with some of his ideas.) He also had a nasty habit of turning troublesome wives into skeletons for use in medical schools. One of the most interesting elements of the book is the way that Larson invites you to ponder whether the fair and Holmes' killing spree are somehow connected - whether they are powered by the same engine. They're both lavish, often gratuitous, exercises in ingenuity, and they both belong to this strange era when America was testing its growing power. Holmes is the dark angel of progress, perhaps, a fitting herald for an American century that would see two world wars and much chaos beyond. We would need all the Cracker Jacks and Shredded Wheat we could get hold of to survive that sort of thing.

Holmes would have liked Columbia, I think, with its deadly Vigors (a perfect extension of the quackery and health crazes of his era), with its face-mangling skyhooks, with its self-immolating nuns, its myriad ways to dole out horrible deaths. That said, if they were being honest with themselves, the creators of the Chicago fair would have recognized a lot of Infinite's city, too.

There's that familiar airbrushing of history that occurs whenever a nation presents its own origin story, for example. (The Hall of Heroes offers a particularly good insight into the Disneyfication of past butcheries - and Disneyland itself was much influenced by the Chicago expo.) There are the toxic social divides, which Irrational uses to great effect. This racist fantasyland in the sky is in part kept moving by the toil of black Americans, Irish Americans, asian Americans: it is a functioning demonstration of the fact that its own dogma does not work.

Then there's the new art of mass advertising, which is already everywhere you look in Columbia, its dark-minded platitudes mingling with propaganda sloganeering until you can't tell the difference any more. ("Strength through leisure!" shouts a sign down by a pretty beach themed around - of course! - battleships: what does that even mean?) In a similar vein, the next decade would have provided the fair's creators with a decent analog for industrialist Jeremiah Fink, too, whose logo invokes both Ford and Coca-Cola - albeit tinged a sickly, absinthe green - while his factory town and his factory lines would become familiar elements of blue collar life in the new century.

Ford even sheds a little light on why Comstock's idealized city is ultimately so much more menacing and self-defeating than Chicago's ever was. One of the first things Booker DeWitt sees on the cobbled streets of Columbia is a motorized stallion pulling a cart - a fabulous but also pretty ridiculous sight echoing Ford's quote that, had he initially asked his automobile customers what they really wanted, they'd have requested a faster horse.

Columbia is the city of the faster horse - the nation of the faster horse in fact, since, following secession, its flag has 13 stripes and a single star. It represents a lunge for progress without any kind of enlightened vision of what that progress should actually look like.

It is the old world - bigoted, cloistered, blinkered, deadly - just sped up a little, which explains why this slice of the future also feels so creaky and so antiquated. It explains why you arrive in Columbia via a rocket, sure, but strapped into a device that looks worryingly similar to an electric chair, and why those founding fathers are employed not in the service of democracy, but in the service of a religious totalitarian state - why they are no longer allowed to be men and must be angels instead.

As with Fink, you don't have to look too hard to find parallels for either Comstock or his enemies the Vox Populi in our own world, let alone that of the 19th century. On both the contemporary far-left and the far-right the connections are so obvious that they can seem a little trite. Like the image of Washington, jaw set, bright eyes strangely vacant, these sort of things seem to come with America as part of the package, whether you're employing fantasy, social realism, satire, or a muddle of all three.

BioShock Infinite doesn't resolve any of the issues thrown out by Columbia's creation or its brisk civil war, but then how could it? America hasn't resolved them either; it's learned to live with the manner in which the gears grind against each other, the way Chicago's fairground attendees learned to take in the uplifting sights while the freezing Illinois wind battered them and snatched away their lollipops.