Before Amiibo Cards, Nintendo Gave Us e-Reader

The notion of transmitting video game data via trading cards may seem strange, but with Amiibo Cards are simply another instance of Nintendo repurposing an old idea.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

There's something deliciously backward about the concept of Amiibo cards. Amiibo themselves make a certain kind of sense — the notion of digitally enhanced toys capable of interacting with video games has been around since long before Toys By Bob came up with Skylanders! — but Nintendo's new line of cards, which launched last week alongside Animal Crossing: Happy Home Designer, takes a reductive approach to toys-to-life that wobbles precariously at the precipice between genius and idiocy.

At their most basic level, Amiibo cards and standard Amiibo serve the same function: They're vehicles for near-field communication chips capable of transmitting data to and from specific games via the NFC reader component of the Wii U and New 3DS systems. Amiibo figurines, however, also possess the same intrinsic appeal as other toys: They're collectible, they beg to be put on display, and they house their all-important NFC chips inside a chunky plastic base. Amiibo cards, on the other hand, are simply that: Cards. Heavy, printed rectangles of paper stock; collectible, sure, but with far less heft and incentive for display. More disposable.

Besides causing Animal Crossing fans to part with ridiculous amounts of money, Amiibo cards serve the somewhat counter-intuitive purpose of adding content to Happy Home Designer (and eventually Animal Crossing: Amiibo Festival, and presumably future main and spinoff titles for the series as well). Yet the idea of tapping paper cards to your console as a means of enhancing a game seems a bit like faxing someone an Excel file; you can do it, but why would you? The cards have sold out basically everywhere, but that's surely a result of the buoying effect of Amiibo frenzy and the appeal of Animal Crossing's expansive cast of characters. The tech itself is ludicrous.

Amiibo cards are not, however, the first time Nintendo has used paper trading cards as a medium for video game data. More than a decade before Animal Crossing Amiibo cards, they produced a series of far more traditional cards for a Game Boy Advance peripheral called the e-Reader. Those cards found moderate success in Japan, primarily as a vector for Pokémon and Animal Crossing data, but they went over quite poorly in the U.S. and barely even saw the light of day in Europe.

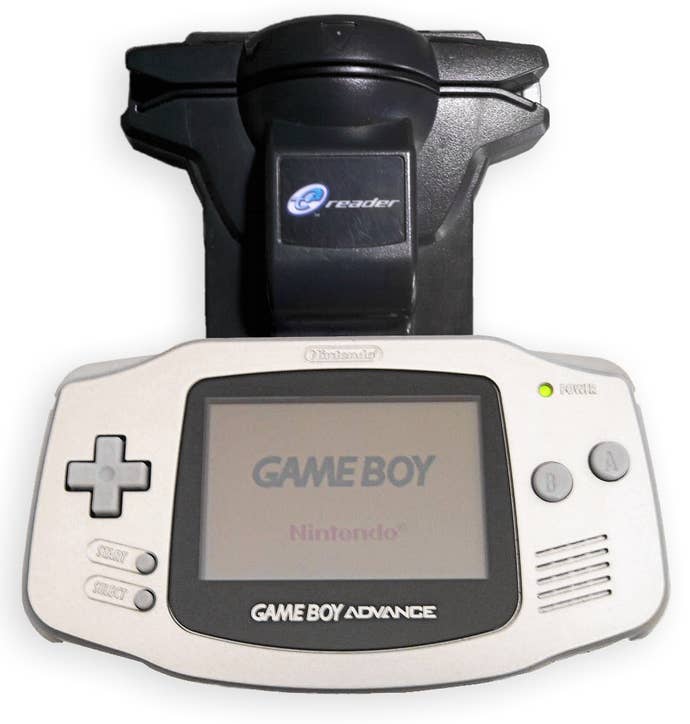

NFC technology existed by the time of the e-Reader's 2002 debut, but it was nowhere near as cheap as it is today, nor had NFC chips been miniaturized enough to allow them to be embedded into trading cards. Thus, e-Reader cards didn't utilize the same tech as Amiibo cards; instead, they worked with an optical recognition system. The e-Reader itself was a thick plastic device that plugged into the cartridge port of a Game Boy Advance and could read cards as they were swiped through the device's card slot. While the mechanism and process were similar to swiping the magnetic stripe of a credit card, the data stripe on each e-card was printed with ink rather than encoded magnetically. An LED sensor inside the e-Reader would scan the tiny printed data code as the card passed through the groove.

Novel and clever to be sure; but this process was also anything but efficient. While e-Reader cards mostly offered bonus content and enhancements for games, they also involved a cumbersome process, to say the least. Because the e-Reader occupied the GBA slot, you couldn't simply boot up a game and scan a card for it; you had to have two GBAs and connect the system running the e-Reader to a GBA running the target game via Link Cable. Likewise for GameCube games that made use of e-cards.

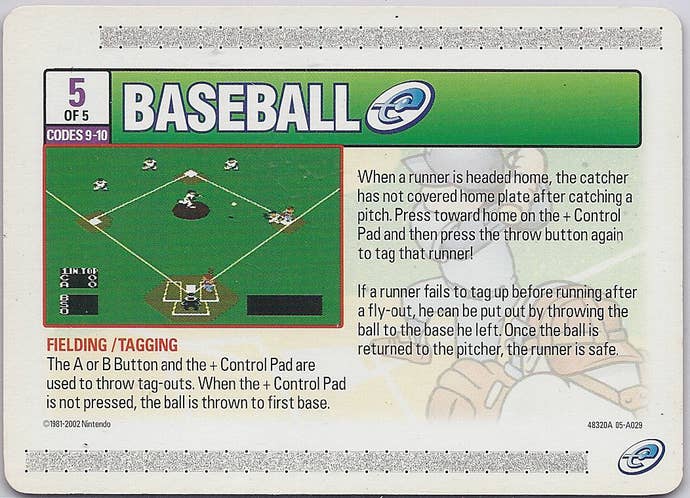

In fact, about the only thing the e-Reader could do on its own was play old games. In one of the more fascinatingly weird product concepts Nintendo has ever come up with, you could buy several NES games in card form. All told, a total of 13 different NES games came out in e-card form (as well as several Game and Watch facsimiles). It was an impressive hack — working NES games, read from paper! — but also far from fun. Each game shipped on five dual-sided cards, meaning that in order to play ancient 8-bit clunkers like Baseball and Urban Champion, you had to swipe cards 10 times per game.

The secret of the e-Reader's NES games? The device actually had a GBA-compatible NES emulator built in, presumably the same one Nintendo would use a few years later for the NES Classics series. Furthermore, it was only compatible with the earliest, simplest NES games, the ones running on the NROM cartridges from the time of the console's launch. There definitely was something amusingly novel about sliding paper cards in order to play actual NES games, but the appeal quickly wore thin. The e-Reader could save a single NES title to memory at a time, so in order to switch from one game to another you had to swipe your cards, every single time.

By far the most interesting application of the e-Reader came in the form of two add-on content packs for Super Mario Advance 4: Super Mario Bros. 3. By linking two GBAs and swiping specially designed cards, you could unlock bonus features in the GBA remake of Mario 3, all contained in a special world called World-e. Among other things, these bonuses included special, never-before-seen levels that folded features from other Mario Advance games into Super Mario Bros. 3. These e-Cards have become quite expensive on the aftermarket, with a full set (including a handful of seldom-seen Walmart-exclusive cards) typically selling for more than $100.

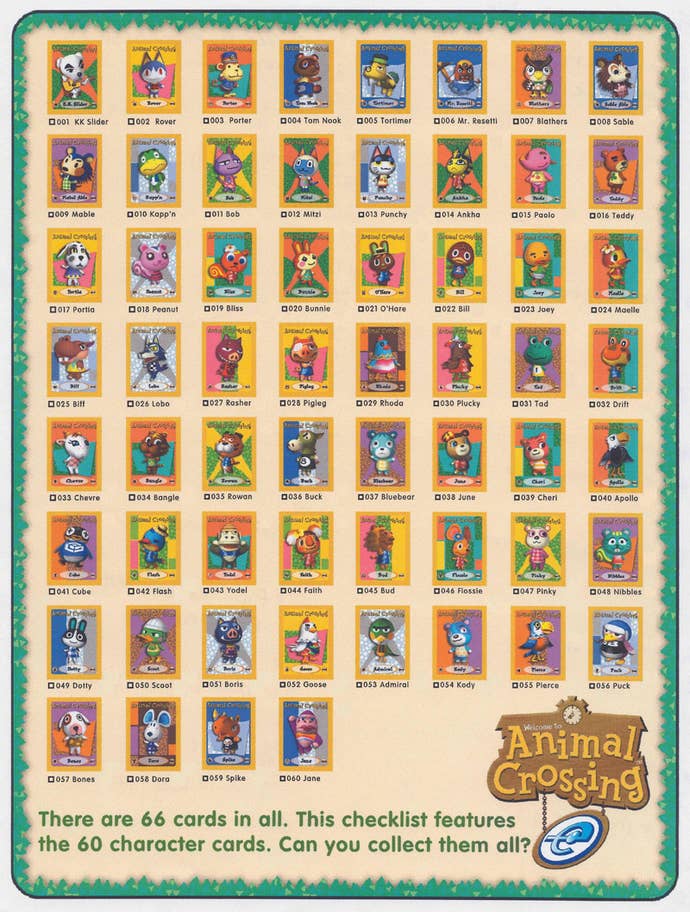

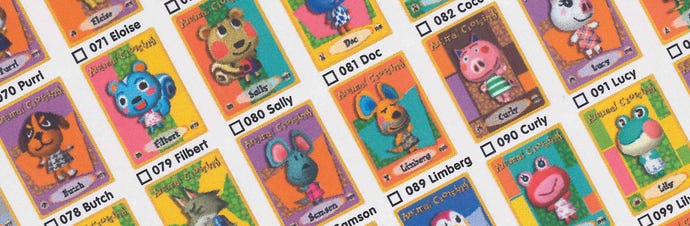

More relevant to the recent Amiibo cards, however, was the Animal Crossing-e series. All told, Nintendo sold roughly 350 different Animal Crossing e-Reader cards (also in blind card packs) across four series, allowing owners of Animal Crossing for GameCube to access unique furniture, minigames, and, yes, even NES games to play. Besides demonstrating why Nintendo chose to kick off their Amiibo card initiative with Animal Crossing (namely, there was already precedent), the Animal Crossing-e series also provides a useful demonstration of the relative strengths and weaknesses of standard cards versus those embedded with an NFC chip.

The price advantage definitely belongs to the classic cards, though not quite by the margin you might expect: While Amiibo cards in the U.S. work out to a dollar per card, the e-cards sold for $3.29 for a pack of five, or 66¢ per card (89¢ adjusted for inflation). The e-cards also offered considerably more diversity in terms of associated content, with both character cards as well as cards that featured items or songs, whereas Amiibo cards feature characters only.

Then again, the Amiibo cards effectively do have items attached, at least in Happy Home Designer: Each villager you invite into the game with a card comes with a few specific pieces of furniture and decor in tow. The Amiibo cards also have a tiny amount of storage built in, so you can save custom information about that villager, presumably for future use. Oh, and there's one other advantage Amiibo cards have over the e-Reader: They're region-free.

Yes, in one of the most bizarre cases of intellectual property protection attempts ever, Nintendo actually region-locked pieces of paper. Well, technically, they region-locked the e-Reader device. While any e-Reader would work in any GBA — the systems themselves had no regional differences — the e-cards were coded to work in specific e-Readers and would only scan in local devices. This means that certain cards which were released in extremely scarce quantities in the U.S. and now command high prices are far more common in Japan, but they won't work on American e-Readers. It also means that, weirdly enough, cards for the region-free GBA were locked to territories, while cards for the region-locked Wii U and 3DS systems have no such restrictions.

In the end, the e-Reader amounted to little more than another chapter in Nintendo's long history of abandoned peripherals. The e-Reader was discontinued after about a year and a half in the U.S., though it did see a dribble of support in Japan from third parties through the end of the GBA's life. It definitely goes in the books as one of Nintendo's less successful peripheral experiments, and it certainly doesn't have the cachet of, say, the Game Boy Camera. I wouldn't call it a complete waste, though; along with the bonus games in Animal Crossing, the NES game cards marked Nintendo's first step toward resuscitating its back catalog. They paved the way for the NES Classic series for GBA, which in turn demonstrated proof of a market for classic games, creating a foundation for the likes of Virtual Console, 3D Classics, and Super Mario Maker.

And, of course, e-Reader was the distant ancestor of Amiibo cards. Its existence doesn't make the idea of transporting video game data in pieces of paper any less odd —if anything, the e-Reader just makes everything weirder — but I suppose it's only natural for Nintendo to gravitate toward cards, given that the company began as a playing card maker. I suppose the real question is: How long before we see Amiibo hanafuda cards?

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)