Back When Screenshots Really Were Screen Shots

Old Man Rignall spins one of his yarns from the olden days of gaming.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The other day while I was taking some screenshots of a new PS4 game, I found myself cursing under my breath at the inconvenience of having to transfer my files from my console to a USB drive, trudge over to my Mac, and then upload them to USgamer's content management system so that they could be incorporated into an article.

Oh, the humanity.

Okay. In all fairness, I was rushing to hit a deadline, and having to fiddle about for a few minutes just exacerbated my anxiety. Fact of the matter is that taking screenshots – especially on PS4 – is about as easy and convenient as it could possibly be. Just boot up your machine, play a game, and press the share button when you want to take a pretty picture. Sure, it can sometimes be challenging capturing an action shot – the console can lag when you're trying to shoot something that's particularly demanding of the CPU, resulting in the actual picture being taken a second or so after pressing the share button – but for the most part, snapping screenshots is a breeze.

Indeed, that's what struck me later on that night after I'd finished my work. As I unplugged my USB from my Mac, I started thinking back to my early days working on games magazines in the 80s and 90s, and what an utter palaver taking screenshots used to be. There was no easy solution back then. Games systems were primitive beasts that didn't have share buttons, or indeed any means at all to snag an image of the screen. Capture boards that you could plug into a PC and make screen dumps while you played the game hadn't yet been invented. These were analogue times, and when it came to taking pictures of video games, you had to use an old-fashioned film camera.

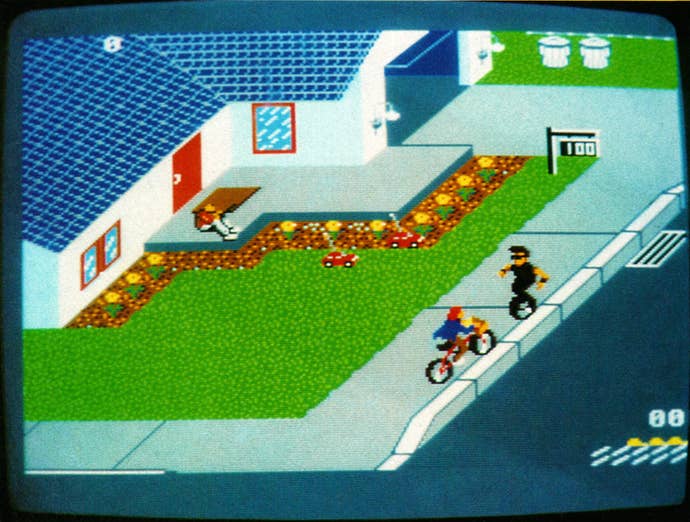

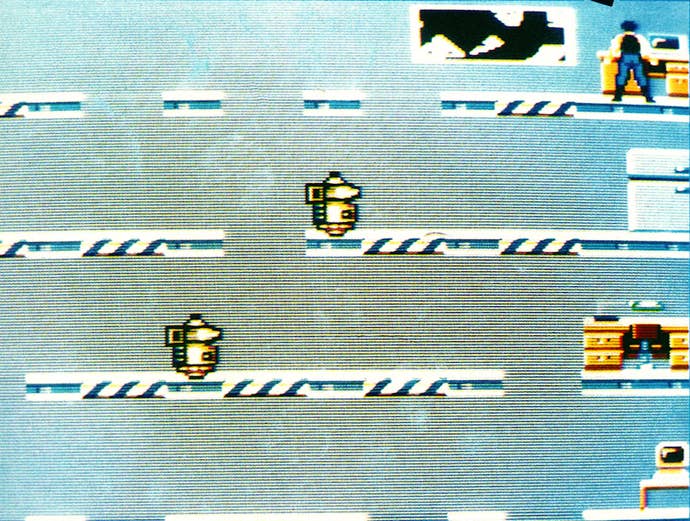

Yep. Those screenshots you used to look at in old games magazines were indeed shots taken of the screen itself.

While this mightn't exactly be a revelation to most, what might be are the conditions that we had to create to capture crisp, print-quality images of your favorite games. Screen glare was the number one enemy of the screenshot: Even the slimmest shaft of light could reflect off a CRT or TV set, ruining a picture, so screenshots had to be taken in the dark. That meant having a dedicated room – preferably with no windows – that was completely blacked out in which the games systems, and TV sets and monitors were located.

These rooms were often not ventilated, and would get very hot - especially in the summer. Because of that, they developed their own peculiar aroma that would assail your olfactory organs until you mercifully developed "nose blindness."

Screens had to be kept pristine, since fingerprints and smudges would show up on a photograph, so they were religiously cleaned before every screenshot-taking session. And the camera was always put on a tripod so that it could be placed directly in front of a monitor and kept steady, because screenshots had to be taken at very slow speed. With oldschool British PAL CRTs refreshing at 24 times a second, you had to take your shots at a shutter speed slower than 1/25th of a second; otherwise you'd end up with a big black refresh line across your picture.

This caused logistical problems when taking pictures of certain games. Because of the slow camera shutter speed, it meant that you couldn't shoot a game while it was moving, because the resultant shot would have motion blur. So you had to pray that the game had a pause mode that simply froze the action, and didn't bring up a menu screen, or the word "PAUSED." If they did, you'd have to play the game very carefully and shoot pictures only at junctures where the action slowed down completely.

Shooting screenshots at shows and conventions was even more challenging. With the bright overhead show hall lights causing massive glare, and the glass screen reflecting everything that was in front of it, capturing screenshots when I visited CES conventions seemed out of the question. Or was it? What I'd do is take a very large, thick blanket with me, which I'd put over the screen and camera, creating an impromptu darkroom that would mostly minimize the light bouncing off the screen. When I first started doing this, I'd get PR people rushing up to me asking me what the hell I was doing, but once they realized I was simply taking screenshots, they'd let me do my thing. And before you ask, almost no publishers took their own screenshots at the time – it was just too difficult, and the expectation was that magazines would always take their own.

Needless to say, wherever you had to do it, taking screenshots was right royal pain in the ass. And that's only half the story. The film had to be taken to a local photography studio to be developed, which would take several hours, even at the fastest possible, that'll-cost-you-extra turnaround rate. The picture selection process involved using an under-lit light table and magnifying loupe to choose the best screenshots, and then they had to be cut out of the negative strip and labeled properly so that the page designers wouldn't get them mixed up. Good times, good times.

While I don’t miss anything about taking screenshots the old way, one thing that I do still appreciate about a well-shot picture of a video game taken from a CRT screen is its aesthetic qualities. The way the pixels blur together on the phosphorescent screen is unique to the period, and you can often see the individual scan lines. It's a cool effect that I think gives those old screenshots real character: A far cry from today's pixel-perfect captures that can be swiftly snapped and shared with the world with just a few deft presses of a button.

Header/Thumbnail photo credit: Flickr user Artemiourbina via creative commons.

Other screenshots taken from Mean Machine magazine, circa 1990.