At 30, Castlevania May be Dead, But Its Influence Lingers Beyond The Grave

Happy anniversary, Simon Belmont! Too bad your bloodline is as deceased as Dracula himself.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

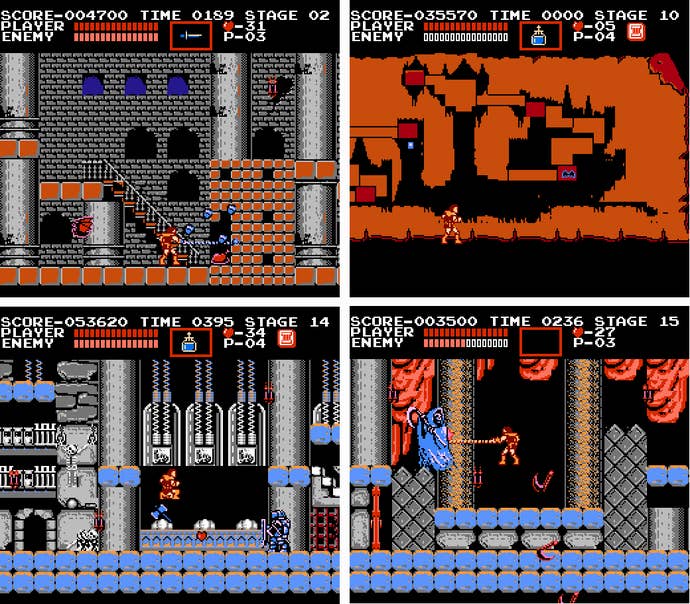

Exactly 30 years ago yesterday, Konami published an unassuming game for the Famicom Disk System (the Japan-only peripheral for the Japanese version of the Nintendo Entertainment System). Called Akumajou Dracula, or "Devil Castle Dracula," it would arrive in the U.S. the following spring with a new title: Castlevania.

Castlevania was one of the first of a new breed of action games emerging on the NES. Heavily inspired by Ghosts ’N Goblins, Castlevania presented players with occult themes reminiscent of those in Capcom's arcade smash along with a similarly steep, even unapologetic, difficulty level. It imposed on its protagonist Simon Belmont the same jump-physics limitations that affected Arthur in Ghosts ’N Goblins: Unlike in Mario's groundbreaking new adventure Super Mario Bros., Simon couldn't change the trajectory of his leaps in mid-air. Jumping was a commitment.

However, Castlevania made one significant change to the Ghosts ’N Goblins formula: It felt far more deliberate in its design. Capcom infused both Arthur and his world with a sort of limber looseness that in many ways served to make the action more difficult — its speedy pacing and furious, numerous, and highly randomized enemies didn't jive well with Arthur's limitations, and the game quickly became overwhelming. Konami ratcheted down the overall speed, slowing Simon's pace as well as that of the world around him. Enemies still appeared in great numbers, but the hero's methodical movements were matched by his foes, giving players more time to react. This didn't necessarily make the game easier, because all of Simon's actions demanded the commitment to the follow-through as his leaps, but it meant that players who understood their protagonist's limitations enjoyed an extra split-second to process and respond to threats.

The comparatively slow pacing of Castlevania may simply have come about as a natural consequence of the game having been designed for NES rather than for the powerful arcade hardware on which Ghosts ’N Goblins originated, but Konami embraced that necessity and made its effects universal. As with the best action games, Castlevania gave the impression that its creators defined the hero's abilities and limitations first, then designed the quest and all its obstacles around those factors. Simon couldn't move quickly, and he couldn't jump very high or far; so, Konami built the game out of blocks that neatly matched up to his actions. Enemies moved in simple patterns and demonstrated small tells to allow you to predict their actions. Castlevania demanded almost pixel precision at times, but if you screwed up a jump or failed to hit a bad guy, you always knew it was your fault. Only a handful of enemies — namely the Flea Men, and Death's scythes — ran the risk of overwhelming Simon with unreasonable numbers, speed, and movements.

Even then, players could arm themselves appropriately for the situation. Castlevania adopted the swappable weapon mechanic present in Ghosts ’N Goblins, but it became fairer and less potentially crippling here. Where Arthur had to choose between sticking with his trusty lance or switching semi-permanently to a different weapon like the torch or cross, Simon always carried a whip. Though weak in its default state, players could quickly and easily upgrade the whip to gain superior strength and reach. Those boosts would be lost upon dying, but it was a simple matter to build it up again in Simon's next life; this created a power penalty similar to the one Konami built into Gradius, though vastly less crippling. However, no matter what, Simon always wielded a whip as his primary weapon, and it always carried with it some constant, basic strengths and weaknesses: The same wind-up animation, the same amount of time Simon had to stand with his weapon extended. No matter what, Simon relied on the crack of a whip to battle evil.

Rather than replacing his whip, then, those extra weapons he encountered along the way served as a secondary function: An alternate way to take on enemies. These worked much like Arthur's shifting armory in Ghosts ’N Goblins (holy water replacing the torch, the dagger working like a lance, etc.), but they complemented the whip rather than overriding it. Because of this, Castlevania's designers could design each and every challenge around a handful of gameplay constants — Simon's speed, reach, and aerial agility — which in turn resulted in a consistent, interesting, and ultimately fair six levels for players to conquer. Castlevania was hard, but it lacked the sense of frustrating randomness and hostility so common to action games the of era.

Unsurprisingly, Castlevania begat its share of imitators. Not a huge number; not like Mario. But a number of publishers turned out their own takes on the Castlevania concept, from the brazenly imitative to the absolutely transformative. The imitators did nothing to elevate the concept; Thinking Rabbit's 8 Eyes for NES attempted to integrate a Shinobi-like companion character but suffered from poor design and weak play mechanics, and SIMS' Vampire: Master of Darkness was decent enough but hilariously derivative.

On the other hand, you had Tecmo's Ninja Gaiden, whose brisk pace immediately set it apart from Konami's creation. Nevertheless, underneath it all, Ryu Hayabusa and Simon Belmont weren't so wildly different from one another. Both carried a weapon that offered decent reach within a fixed range. Both could collect limited-use subweapons to complement their standard attacks, which ranged from a quick weak projectile to a time-stopping device to a flame-based power employed at a 45-degree angle. And most of all, both heroes graced the player with very precise, very specific control mechanics that gave them the tools they needed in order to overcome the challenges before them.

Ryu had modest jump power, like Simon's, and while he could alter his direction in mid-air to a certain degree he nevertheless was constrained by the need to commit to an action to a significant degree. Enemies in Ninja Gaiden appeared quickly, frequently, and without mercy, meaning that haphazard actions guaranteed failure. But, as in Castlevania, foes appeared at fixed locations and obeyed set rules. Learning the ins and outs of each level as well as its innate rhythms became the key to success — as in Castlevania. Playing the two games well ultimately felt much alike and demanded the same mental discipline, albeit at very different speeds.

In Ninja Gaiden, we see the roots of Castlevania's long-term influence on game design. It presented a new and novel approach to challenge, a result of the post-arcade era of game design: Not to throw crap at players haphazardly in order to drain their quarters, but to present a series of constant threats that players could definitely handle with the tools available to them — but only after practice.

Konami struggled to make that formula work for Castlevania beyond the NES. The most successful rendition of the classic Castlevania tenets appeared in the hard-to-find Dracula X: Rondo of Blood (a Japan-exclusive PC Engine CD-ROM game), and soon afterwards the series shifted to a Zelda- and Metroid- inspired action RPG format with Symphony of the Night and the subsequent adventures produced by Symphony co-director Koji Igarashi. Meanwhile, the series' attempts to take its rules into the third dimension never panned out, resulting in uniformly middling creations that lacked both the tactile precision of the NES titles and the satisfying depth of the Symphony-esque 2D games.

One game that did manage to recreate the Castlevania feel in 3D, however, was Capcom's Devil May Cry. Arriving shortly before Igarashi's first 3D Castlevania game, Lament of Innocent for PlayStation 2, DMC invited unflattering comparisons — unflattering for Lament, that is. Where Lament felt sluggish, padded, and imprecise, DMC kept up a snappy pace, demanded expert control, and offered players a compelling interactive feedback loop through its brilliant combo system. Both DMC and Lament featured gorgeous gothic visuals and great music, but only one of them was a pleasure to play... and it wasn't Castlevania.

DMC would become the foundation for numerous games its creators would go on to create under the banner of different developer and publishers, from SEGA's Bayonetta to Konami's own Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance. Castlevania, sadly, never quite recaptured its own legacy, and now appears to have been phased out along with most of the rest of Konami's extensive catalog. Its lessons have spread beyond DMC and the subsequent Clover and Platinum libraries, though; most famously, From Software's Souls series has essentially taken up the Castlevania mantle with its complex, methodical, mastery-based action in grim-but-elaborate gothic worlds. The Souls games have managed to combine the demanding, precision design of the NES Castlevania adventures with the expansive interconnected environments of Symphony and its offspring — something Konami never figured out how to accomplish.

At this point, ex-video game publisher Konami seems unlikely to return to any of the classic franchises that helped build the company's sterling reputation in the first place, meaning Castlevania's last word will probably be the erotic violence of its casino games, or the wet fart that was Lords of Shadow 2. But the series' influence lives on through oblique relatives like Bloodborne as well as through more direct references, like Odallus: The Dark Call. And it may not wear the Castlevania name (or the brisk NES design style), but Igarashi's Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night definitely feels like the real deal and will almost certainly be worth the wait once it arrives in 2018. Much like Dracula, the villain who lent his name to the franchise in Japan, Castlevania's influence continues to be felt beyond the grave.