A Pioneering Game's Journey: The History of Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail co-creator Don Rawitsch talks about the game's history, from its humble beginnings to its induction into the World Video Game Hall of Fame.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

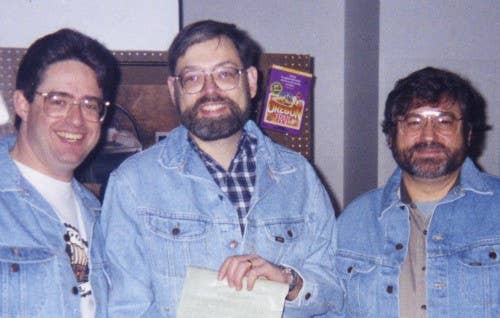

Many kids who grew up in the 70s and 80s had their first encounter with a computer while at school. And oftentimes, the first game they played on it was Oregon Trail, a groundbreaking educational title that was created in 1971 by a trio of teachers-in-training: Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger. From its humble beginnings, Oregon Trail has gone on to sell an astonishing 65 million copies, and last year was inducted into the World Video Game Hall of Fame.

However, despite its huge success, the game wasn't initially intended to be a commercial enterprise. Indeed, it wasn't even originally designed to be a computer game; it was borne from the concept of a card game conceived by Don Rawitsch as a novel way to teach kids history. Don tells me this during a conversation I had with him ahead of the Orgeon Trail Classic Game Postmortem presentation he delivered at GDC 2017.

"As a senior in college, and as an aspiring teacher, one of the things that you do is your practice teaching," explains Don. "You get assigned to a school under the tutelage of a real teacher for two to three months, and it gives you an opportunity to get a sense of what schools are like and what teaching would be like, and whether you actually had the (laughs) courage to do it. But after you had been in the school for several weeks observing, then your supervising teacher would say I'm going to turn over my classes to you in a couple of weeks, and you need to be prepared to do this. So, my assignment was to prepare to teach about the migration during the 19th century of the population of this country from east to west, which is a pretty significant historical occurrence. At that time, I didn't really know anything about computers, but I had heard about and experienced games that educators were creating, not on the computer, but board games. So, I thought, maybe the trip over the Oregon Trail could be made into a box game."

"I started to create a map, thinking about, are the players going to turn cards over, are they going to roll dice, how is this going to work, to show their progression along the trail. And I hadn't gotten very far into that when my two apartment-mates, who were also prospective teachers and who had had a little bit of computing experience in college, came home, saw this stuff on the floor, and said, well, that's a very innovative idea for teaching about the westward migration, but it would be even better if we could somehow put it on a computer. So I said, I have to start teaching this unit in two weeks. Can we get something done in two weeks? And they lied to me and said yes. But, we did!"

"During development, my job was to inform them about what would have happened on this journey that these people took. This was 2000 miles and six months in a covered wagon – a pretty arduous thing to do, and full of adventure. I would talk about what would happen on the trail and they would think about how that would convert to a game. They chose a very straightforward game format in which the player takes turns. So, we had to program the computer to determine what's going to happen in each of these turns. And they also, I'm kind of thinking about today's gaming terms, added elements of resource management. So, you the player get resources, then the game throws obstacles in your way and you use your resources to solve those problems and hopefully get to a goal. We assigned the player food, oxen, clothing, bullets, and things like that that they would need, and as they took a turn, the computer would tell the player what had happened to them, or what they were currently experiencing. The player would then react using the choices given, and the computer would keep track of how that affects the resources."

Funnily enough, for a game about pioneers, the developers of Oregon Trail were also treading unfamiliar ground. Don explains, "Nobody had written a book on how to create computer games. Nobody was teaching any courses on how to do this. As a matter of fact, when educators approached computing, they tended to try to create applications that replicated what the teacher used to do: I'm going to quiz you on your math facts. I'm going to show you words and you determine if they're spelled correctly or not. Oregon Trail, although we didn't realize it at the time, was really on another level conceptually. And the idea here was to put the player into a story and have the player make decisions and deal with keeping track of things and over time learning a strategy, and in the process learn something about history, geography, resource management, things that would apply to what they were supposed to be learning in the classroom anyway."

"History is often ranked very low on the enjoyment scale by students because they see it as a never-ending parade of reading things and then having to remember facts, and give them back to the teacher on a test. So, I wanted students to understand, when we said moving west, what did that mean to the people that did it. But instead of me lecturing about that or having them read about that, I thought it would be much better to engage them in something they would find challenging and enjoyable, and the learning would stem from the experience. And I believe that we saw evidence of that when we first used the game and then when the game began to get more widespread use."

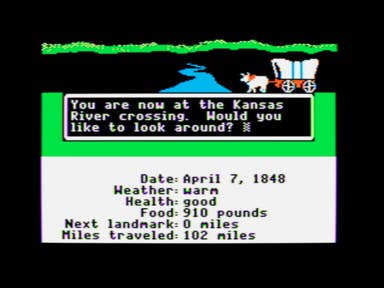

The first iteration of the game was produced on an HP 2100 minicomputer that users connected to using a teletype machine. "Everything was done in text," reveals Don. "There were no audio-visuals, no images, no screen. And the other thing was that even though the schools of Minneapolis had this accessible to them, typically, that meant in a school, they had one teletype. So, one student, or maybe one class could be interacting with the computer at any given time. My strategy was to divide them into small groups and set up a rotation of activities. So, at any given time, any given day, one of those groups of four or five kids would be on the teletype, and another group would be doing a map exercise, another group would be reading something – perhaps fiction that's been written about the pioneer days. Then, I would keep rotating them day by day until every group had a turn to do every activity, including the one that they wanted to do the most, which was the computer. So, I thought that was a reasonable teaching strategy to use, to make use of the resources that we had."

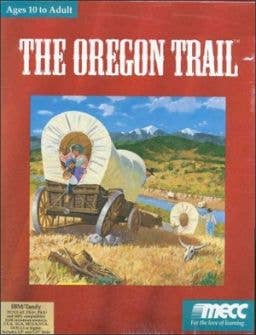

While the kids loved playing Oregon Trail, it was initially only used for a very limited amount of time. Don explains, "When we invented the game, we had a couple of weeks to use it in the schools we were teaching in. So, there were three schools that knew about it, essentially. Then, a couple of years went by. We went back to college to finish our courses and we didn't have access to computers, so, a couple of years went by where the game was kind of in the closet. But, when I got a job at MECC (Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium) in 1974, I brought it back and put it up on the statewide computer that all the schools were connected to. So, starting in 1974, schools all over Minnesota were discovering and experiencing the Oregon Trail, and one of MECC's missions was to create a staff of trainers that went out across the state and gave workshops and held conferences for teachers so that they would understand what the potential was for their particular curricular area."

"This was Minnesota's secret for about five years, until one day at MECC we noticed in a Radio Shack catalogue that they were selling a computer you could own in your house, and then, of course, a lot of news started coming out around Apple and their new products. So, we could foresee that there was going to be this significant shift in how computing was done, and that schools were going to be much more interested in buying lots of inexpensive computers that they could own as opposed to paying "rent" to use a large computer that everybody shared. So, a team was put together at MECC to convert some of the more popular and useful programs from the mainframe to code that would work on, for starters, an Apple II. So, we started creating diskettes with these applications on them, and we gave this away to the schools of Minnesota, because again, our operation was already funded by the state. For a year or two, that's the way it was, but then, some of these diskettes started crossing the borders of Minnesota, and people from other states, let's say who came to conferences, could see these products being demonstrated. We started getting calls, because there was no other publisher that had as much content on an educational basis. There was nothing else to compete with what we had. So, we then had the brilliant idea that maybe they'd pay for this in the other states, and sure enough we were turned into a business because of this shift in how computing was going to be done. So, I always like to point out that we created this very innovative system of the other 49 states subsidizing computing in Minnesota, because we had the products that they wanted. And after a while it became clear that of all the diskettes that we sold, there was one that was selling quite a bit more than the others. Guess which one that was?"

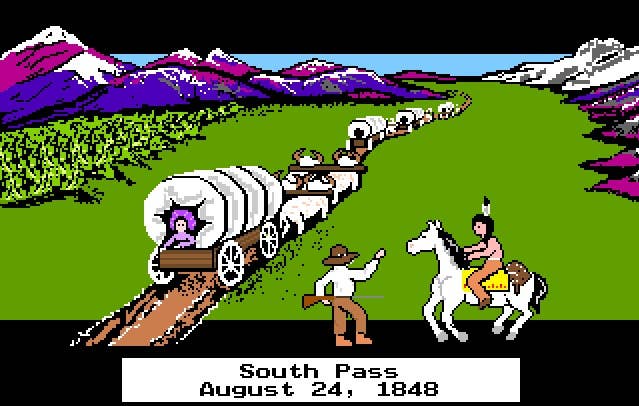

During the process of porting Oregon Trail to Apple II, the game was visually upgraded. Don notes, "The team that converted the code also added some graphics. At first they were somewhat primitive, but by about 1985 we came out with a version that had color graphics. The computer played pioneer songs when you traveled the trail, and you could now actually shoot at things in the game. I always like to say that Oregon Trail might have been the first first-person shooter game, because there was this little guy with a rifle that would shoot buffalo and deer so that you could increase your food supply."

The new version of Oregon Trail continued to prove very popular through the 80s, as did updated Mac and PC iterations that were released in 1990, 1992, 1993, and 1995. At this point the game was generating around $10 million a year in revenue for MECC, and educational software was seen by many as a hot commodity. Don picks up the story, "I was at MECC from 1974 to 1990, and just after I left, MECC was approached by an investment group that wanted to purchase this entity from the state of Minnesota. They paid about $5 million dollars, and left the staff in place, and MECC continued to work. After about five years, in 1996, educational software started getting packaged for home sale as well. There were people in the industry who believed that the home software industry, especially for products that could teach your kids something, would become the next big thing. So, there were some companies that went around buying things up like MECC and The Learning Company and Brøderbund and some of the more successful brand names."

"MECC was sold again to a much bigger company. Remember, the state had sold it for $5 million. The company that bought it from the state got about $130 million for it. However, the story has kind of an unhappy ending, because it turned out the market for home education software was not nearly as big as people thought. So, the companies that had paid millions and millions of dollars to buy up all these companies now had all these software products that they couldn't sell very profitably. That created an opportunity for educational publishers like Houghton, Mifflin, and Harcourt to come in and buy up a lot of these products at a bargain price. The problem is that the former textbook company didn't really know what to do with the software. Now all the educational publishers have technology products, including HMH, but they were never able to really leverage this intellectual property that they published, and prolong the life of some of these applications."

Fortunately, though, Oregon Trail evolved again to find a new market. Don explains, "HMH contracted with a gaming company to take the Oregon Trail idea and upgrade it and make it so you could run it on tablets and phones. If you Google Oregon Trail you can probably figure out how to buy this thing, which is now about five years old. But, the people that did the work, they were not educators, and they turned it into more of an arcade game format than an educational simulation of history. That's probably something people have had fun with as well, but it didn't really help the educational mission that the game was originally created for."

While the game was being ported to mobile platforms, it reached its 40th anniversary. Don notes, "Being a historian, so to speak, those kinds of anniversaries are meaningful to me, and I started doing a little promoting of the 40th anniversary. That happened to coincide with the phenomenon of the kids from the 80s, who really saw the game as their own - I've heard them referred to as the Oregon Trail generation - finding out about the anniversary. All of that interest that they used to have and that fondness for the game resurfaced. Since then, I've done a lot of speaking about how Oregon Trail came to be, and gotten a lot of enjoyment out of meeting people and hearing from those who got a lot out of the game and enjoyed it. I got four minutes on All Things Considered on National Public Radio, and did an AMA on Reddit, where two thousand people asked me stuff in one day. So, it's been a lot of fun, and last year, Oregon Trail was enshrined in the World Video Game Hall of Fame, of the National Museum of Play, which was quite an honor. It's a phenomenal facility – everybody should go there and see all the things they used to play with as kids. There are twelve computer games enshrined. Oregon Trail is the only one that was created with education in mind, so that's quite an achievement, I think, for having stumbled into it. The three of us take a lot of pride in that."