A Link to the Past Deep Dive, Part 4: Why A Link to the Past's Dungeons Were Perfect

CLASSIC DEEP DIVE | In transforming dungeons from combat gauntlets to complex puzzles, the third Zelda reinvented the action RPG.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Design in Action is a weekly column by Retronauts co-host Jeremy Parish that explores games both new and classic, analyzing the way their various moving parts work together to make them great. Currently: A Link to the Past redefined Zelda games, and action-RPGs at large, 25 years ago. We explore why this 16-bit classic remains the standard for the genre.

I couldn't possibly spend a month writing about everything that made The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past so brilliant without taking a long, meaningful look at the game's dungeon design. ALttP has proven itself an influential work in many, many respects, but nothing about this game has shaped the past 25 years of action-adventure games the way its dungeons have.

The latest Zelda sequel, Breath of the Wild, has proven somewhat controversial among fans for Nintendo's decision to more or less remove dungeons from the game. The closest you really come to the classic Zelda labyrinth are the puzzle-laden Divine Beasts. Yes, you can challenge the shrines that litter Hyrule, each of which contains its own dungeon-like puzzle or combat scenario, but they're not the same thing.

In theory, you could see the shrines as "deconstructed" dungeons, like going to a fancy restaurant and having a "deconstructed" dish where all the various components are served separately. However, with an expensive gourmet dish you at least have the option of just putting a little of each ingredient in your mouth all at once to recreate the full experience. With shrines, not so much. See, beginning with ALttP, dungeons in Zelda ceased to exist as a collection of disparate challenges or obstacles and became instead cohesive, layered creations. Each dungeon in ALttP has its own personality, theme, or central mechanic, and each one makes use of those specific elements repeatedly throughout the moment-to-moment play. However, an even greater design revolution came in the way those puzzle elements interlock to turn each dungeon into a complex, unified whole.

Think of the dungeons in this game as a deliberate, jumbled ball of yarn, with multiple loose ends of thread poking through. You want to unravel it and get to the shiny crystal at the center, but in order to do so you have to pull at the threads in just the right order. You tug at one until it won't give anymore, then study the ball to find the next thread, and the next. At some point, you loosen up the first thread you were tugging at and go back to work on that some more. Study and repeat, until you finally reach the center.

This is the element that Breath of the Wild's shrines lack—which is not necessarily a bad thing. Zelda needed a change, and the series' dungeons have built on the concepts presented in ALttP without really doing much of anything to innovate on them. Instead, they simply became larger and more intricate as they moved into the third dimension, bloating up from the generally quick and painless (water shrine notwithstanding) challenges of Ocarina of Time to the sprawling, often burdensome affairs of Twilight Princess. By the time Skyward Sword arrived, Zelda dungeons had grown so massive and complex that they had become show-stoppers: Get stuck in one and your overall progress through the adventure would grind to a halt.

Here in ALttP, however, they're simply perfect. Challenging, yes; complex, definitely. But reasonable in size, and rarely your only way forward: The Dark World allows players to jump around to different dungeons in various orders. You need certain key items to fully navigate the Dark World, and each of those items appear within the dungeons—the Magic Hammer, the Hookshot, and the Titan's Mitt—but the game takes a fairly lenient approach to progression and allows you to wander around and explore the world if you become stuck. Though that's never necessary; one of the most brilliant design traits of these dungeons is that they're fully self-contained. If you can reach a dungeon, you can complete it, because you'll find everything you need to triumph within.

As a matter of fact, this probably stands as the single most influential element of ALttP's design: The idea that each "level" of a game contains the tool you need to complete it. This concept hadn't fully taken hold at this point, so it's not specifically true for every single dungeon; there are a few you can finish without hunting down the treasure stashed in the Big Key chest. Nevertheless, it's true enough, and it turns most dungeons in ALttP into the self-contained puzzles that we all love. Usually it works like so: You need to pass an obstacle that requires the tool or weapon contained in a special treasure chest; but in order to open the chest you need the Big Key to the dungeon; but before you can find that you have to solve a number of other navigational puzzles that may involve finding keys to unlock individual doors, shifting between floors of the dungeon, or completing combat challenges.

But that's not all. Many dungeons are integrated into the larger world of Hyrule, demanding you sleuth out their locations or how to reach them. This may involve finding a hidden trans-dimensional warp tile in a previously inaccessible location of the Light World, passing through a convoluted series of tunnels, or using a magical emblem to open a pathway.

On top of that, ALttP's dungeons incorporate another key design consideration: The player. There's a progressive component to the labyrinths in this adventure which require players to carry forward not only the equipment and health upgrades Link carries, but also the knowledge they accumulate themselves in the process of exploring the game world. An action or trick that shows up in an early dungeon will often appear, in a far more subtle manner, sometime later in the game. So not only do you need fresh equipment acquisitions in order to conquer ALttP's dungeons, you also need to draw upon cumulative experience.

This probably sounds obvious, but that's only because ALttP has been so widely imitated by so many other developers through the years. Consider video game dungeon design before ALttP, in both pure RPGs or action-RPGs like Zelda. Generally they simply consisted of combat slogs, a relentless series of monsters to overcome while mapping your route to the boss. The most intricate action RPG dungeons to be found before ALttP arguably came in the form of Ys III, which had some metroidvania-like elements, but nothing on par with the clockwork intricacy of ALttP's palaces. This Zelda sequel redefined the entire concept of the action RPG and the nature of dungeons. There were terrible monsters to be bested within, yes, but combat skill would only get you so far.

There's honestly enough to unpack in this game that I could devote an entire column to each dungeon. For now, though, let's look in brief at the first labyrinth of the Dark World. How does it works? How does it draw on the game's demand for multiple skill sets?

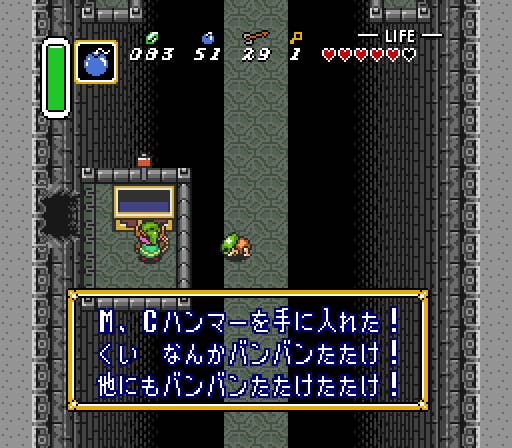

The first Dark World dungeon, the Dark Palace, is one of the few that actually does have to be completed in a specific order. It's a sort of load-bearing puzzle within the Dark World, and the tool hidden within its walls — the Magic Hammer — is required in order to access most of the rest of the world. You can't reach most dungeons without the Hammer. And while you can reach the second dungeon without it, you'll find a critical puzzle element within locked behind a barrier that can only be cleared with the Hammer.

But first, you need to use the Hammer to complete the first dungeon itself. Several paths within the Dark Palace are obstructed by stakes or pop-up barriers that have to be flattened with the Magic Hammer. These demonstrate the fundamental philosophy of ALttP's dungeon design, really: You can navigate much of the Palace from the outset, so long as you can figure out the requisite visual and spatial riddles, but the Magic Hammer barriers present a fixed obstacle that limit and redirect your movement until you can acquire that tool.

The process of actually finding the Magic Hammer involves drawing on a fair amount of knowledge from your time conquering the Light World. For example, one apparent dead-end in the Dark Palace requires you to fire an arrow into the eye of a statue... which might seem unreasonably oblique but for two factors. First, the in-game map reveals the room is much larger than it initially appears, meaning it contains a somewhat obvious secret for the attentive. And secondly, the statue is conspicuous in its placement — it's a different color than the other statues throughout the Palace — and it also happens to be the exact same kind of statue you had to defeat throughout the Light World by popping it in the face with arrows. The clues are all there, but it's incumbent on the player to string them together and formulate the solution.

Similarly, the Dark Palace requires players to leap down to the lower levels at several points. The game presents the prospect of falling into holes or off ledges as a dangerous hazard from the very opening moments, when you could knock royal soldiers into the depths of the castle while rescuing Zelda, so this would appear a counterintuitive action. Or it would, that is, if not for the time you spent in the Tower of Hera. Several points in the Tower of Hera required players to drop down from one floor to the next; plus, unless you were very lucky while fighting the dungeon boss, you inevitably discovered that you could be knocked or pushed to lower levels and have to climb your way back up.

The Dark Palace demands you resolve the difference between safe and deadly falls. The trick, of course, is to pay attention to what you can see below: If you fall into a hole or pit fading to deep black, you've blown it. However, if you can see another layer of floors below, you can leap with confidence, as you'll land safely on that visible flooring. This was somewhat evident in the Tower of Hera, but divining the difference is mandatory here. And the Dark Palace puts a new wrinkle on the puzzle. At several points, you need to bomb fragile spots on the floor in order to reveal a target on a lower level. This is tricky, because there's damaged flooring all throughout the Dark Palace, and some spots are simply bottomless pits. You need to bomb, yes, but also to look before you leap.

And so it goes for every dungeon throughout the Dark World. The second labyrinth yields the Hookshot, which doubles as a navigational tool to carry you across pits and as a weapon. In order to acquire the Hookshot, though, you first have to figure out the secret of altering water levels across dimensions. Incidentally, the second dungeon's boss, which can only be defeated by using the Hookshot to pull away and destroy its protective shell piece by piece, would become the standard for 20 years of Zelda dungeons: A guardian that could only be defeated by using the tool or weapon housed in its lair. The third dungeon yields the Fire Rod, which is essential for opening up the second half of the dungeon — which means that in order to complete the stage, you need to think back to the Light World's Desert Palace and the way it was broken across multiple standalone structures linked by the overworld. You also need to find new workarounds for the star-shaped switch tiles that reconfigure the layout of a room, a fresh permutation for another element that debuted in the Tower of Hera.

This approach carries through to the end of the quest and Ganon's Tower. And while some of this essential character has been abandoned for the latest Zelda, you can hardly blame Nintendo for wanting to freshen things up. The dungeon puzzle concept that made ALttP so revolutionary 25 years ago has been repeated and imitated across the spectrum, in practically every series that involves dungeon-like structures. From Lufia to Persona, Final Fantasy to Darksiders, modern dungeon design owes everything to ALttP. Even first-person shooters with puzzle sensibilities (e.g. Half-Life 2's physics problems) owe a debt to Zelda. ALttP was the first time the brilliant puzzle design of text adventures like Zork had properly been represented in an action context, and it changed the medium forever.

Next time: I could keep going on about Zelda, but it's time to move along to a much more recent game... though one that admittedly feels rather retro.