A Brief History of Games Journalism

Over the past four decades, games journalism has undergone some major evolutions. We look at how it's changed over the years.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

I've called this piece "The Brief History of Games Journalism," but to be honest, the term "games journalism" doesn't sit particularly well with me. I don't necessarily categorize games writing as journalism per se.

There are elements of journalism in what we do - mostly seen on business-focused and high-end intellectual sites where fact-reporting analysis with little personal interpretation makes sense in terms of professional industry coverage. Consumer-facing sites and publications, on the other hand, tend to be far more enthusiast in nature. While some do try to be a little more reportage than others, most sites are far more entertainment-focused in their tone and style, where you expect the writer to be an ardent proponent of the fundamental subject matter he or she is talking about. The general expectation is that the author of a piece is a knowledgeable advocate about their specialized topic - something that's not always true in journalistic coverage of broad subjects and events.

What I've just described are pretty much the traits of what used to be called the "enthusiast press", back when magazines were the only option when it came to video game information. It's a style of reporting that's seen across many different areas of consumer interest, particularly entertainment, and it's a legitimate and accepted form of writing. I just see it as different to the more impartial news-oriented, investigative form of traditional journalism that dates back to the early 18th century.

And speaking of which, the traditional press wasn't particularly interested in video gaming during its early years. It was seen as more a novelty than a genuine form of entertainment. However, when Exidy's Death Race appeared in 1976 featuring gameplay that enabled players to deliberately drive over people, the resultant political furor suddenly got the press very interested. Indeed, it helped set off a decades-long attitude of "games are evil," that still exists in some corners of news journalism and political auspices even today.

The Beginning

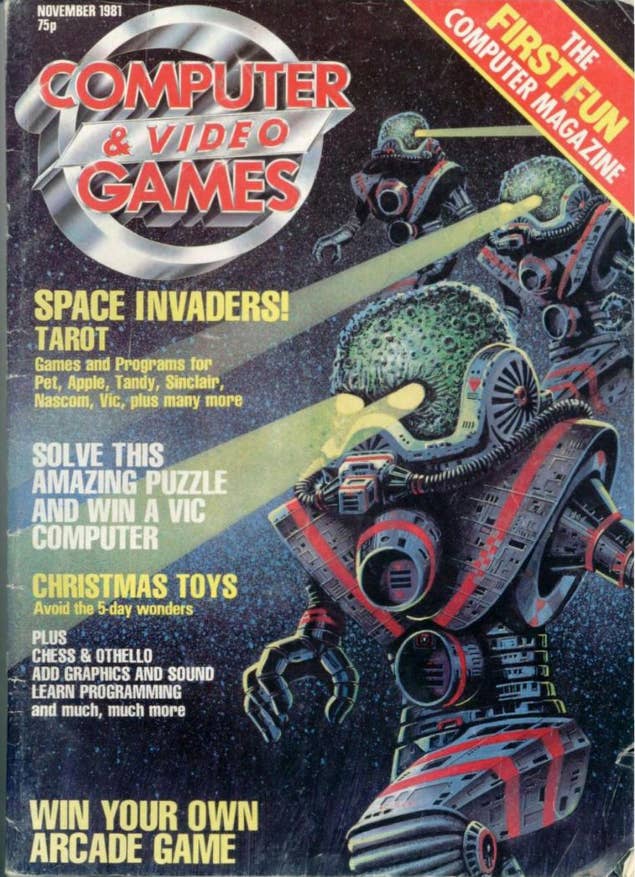

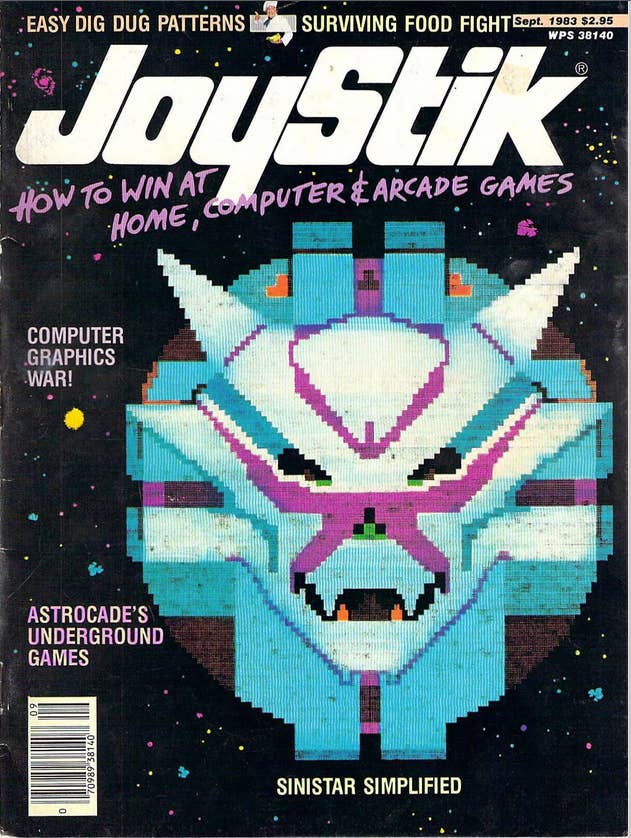

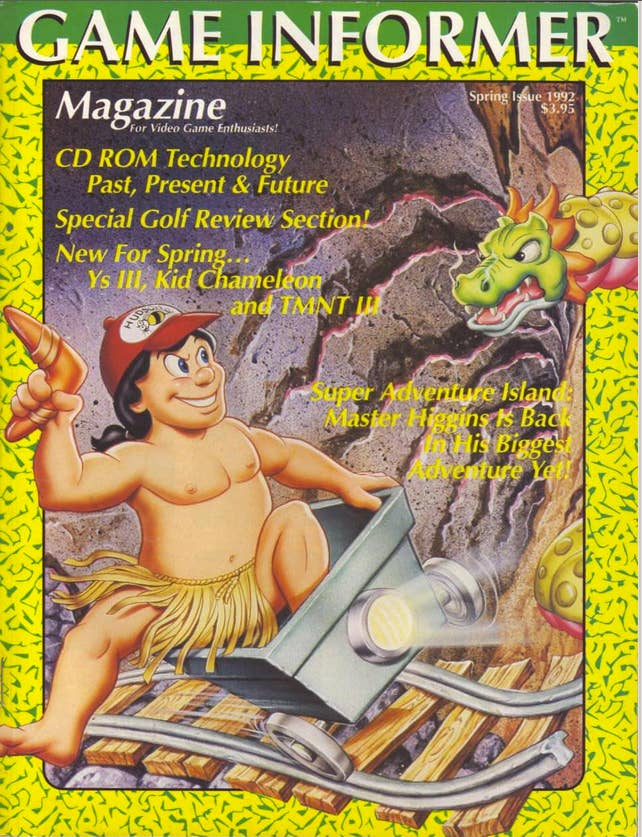

Back in the mid 70's, there was no dedicated video games press. The closest thing to that was trade periodical Play Meter, launched in 1974, which covered arcade games, but very much from a business angle. The first consumer gaming magazine wouldn't appear for another seven years, when, in November of 1981, British publishing company EMAP launched Computer and Video Games magazine.

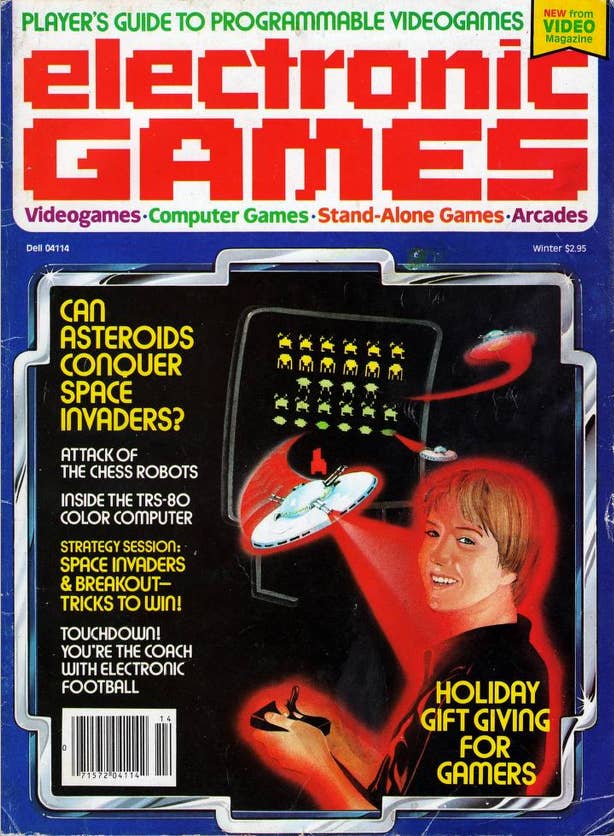

Just a couple of weeks later, the first US games magazine appeared in the form of Electronic Games magazine. Founded by the late Bill Kunkel and Arnie Katz, both these pioneering journalists had covered games for Video magazine, but this was the first time a magazine completely dedicated to gaming had been seen in the states.

In Europe, CVG covered all aspects of video gaming, and also included type-in BASIC listings – simple games that users could input themselves, should they be so inspired. These listings were often long, complex, and sometimes even buggy (wait ‘til next month for the fixes!), and the fruits of the painstaking labor required to enter these reams of BASIC text were often barely worth it. Still, these listings did help hopeful young programmers learn the basics of programming, so they were of use for sure.

In the states, EG focused purely on commercial products, and avoided any aspects of DIY gaming. Where CVG and EG shared common ground, though, was in their style of writing. Since this was the very dawn of games writing, there was no precedent in terms of tone and style of games coverage.

The writers of the era were all trained journalists, and even though they were often games enthusiasts, you can nevertheless see a more classical reporting style coming through in what they wrote in those early days. It was more restrained and less hyperbolic than the style of games journalism that would emerge only a few years later.

Evolution One

With an industry that was in the midst of a revolution, and with an audience that was fervent and extremely excited by what was going on, the lack of visceral enthusiasm in existing magazines was seen as an opportunity by the new wave of publications being launched in the mid-80’s – especially in Europe. Magazines created by journalists-turned-gamers began to feel somewhat staid and unexciting. Also, many of the writers of the time didn't necessarily have the in-depth, expert knowledge of their gaming readership – so to fill that gap, magazines began to hire gamers-turned-journalists. Essentially, up-and-coming writers with deep gaming knowledge who could talk to the readership using the same terms and slang they spoke.

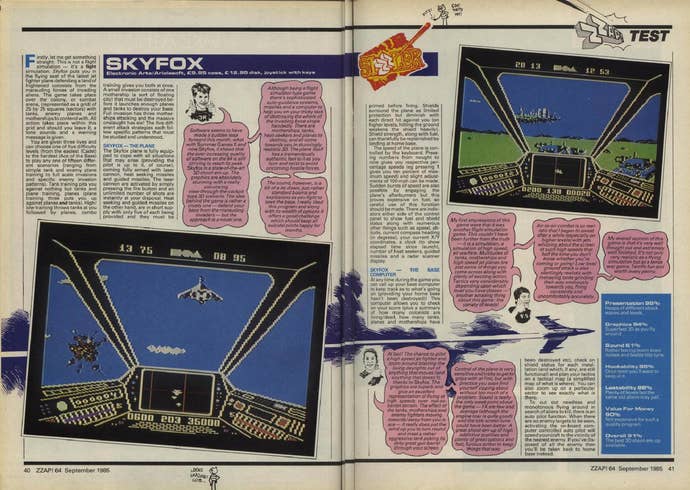

A British magazine called Personal Computer Games was one of the first to do this, followed by CRASH magazine – dedicated to the ZX Spectrum micro – which turned things on its head by featuring reviews written by kids local to the magazine’s offices in Ludlow, England. The magazine where I got my first gig, a Commodore magazine called ZZAP! 64, featured a team that was exclusively gamers – which resulted in a magazine filled with slang terms and contemporary phraseology that resonated with gamers.

However, while some more traditional industry folk saw this sort of writing as “amateurish,” the readers responded very positively. Finally, there were magazines that spoke their language and mirrored their enthusiasm. The odd typo and sometimes poorly constructed English didn’t matter: what counted was that these reviewers were "real" gamers who really knew their stuff – and were excited to talk about it.

Of course, not all magazines followed this style. The more news-focused trade and consumer weeklies, and slightly more academic broader interest computer magazines still continued to report in the more traditional journalistic style, essentially resulting in two types of magazines – the "serious" games industry press, and the more hyperbolic consumer/enthusiast gaming press.

Something that's important to note is that at this time, many readers of magazines were quite young. During the 80's, the average age of a computer magazine reader was 16 years old, because kids welcomed gaming with open arms, while adults were much slower on the uptake. This also had a certain influence on European magazines, where younger readers often saw more colorful expression and puerile humor as positives, and weren't shy about writing into magazines and letting the writers know this.

Europe's Boom. America's Bust

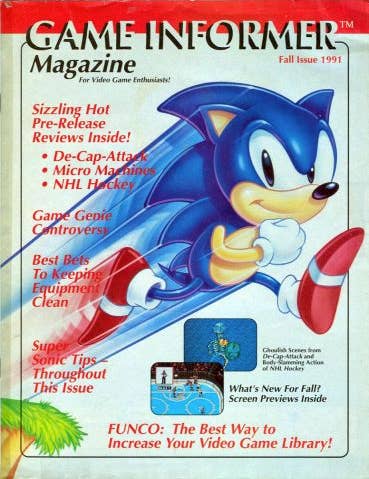

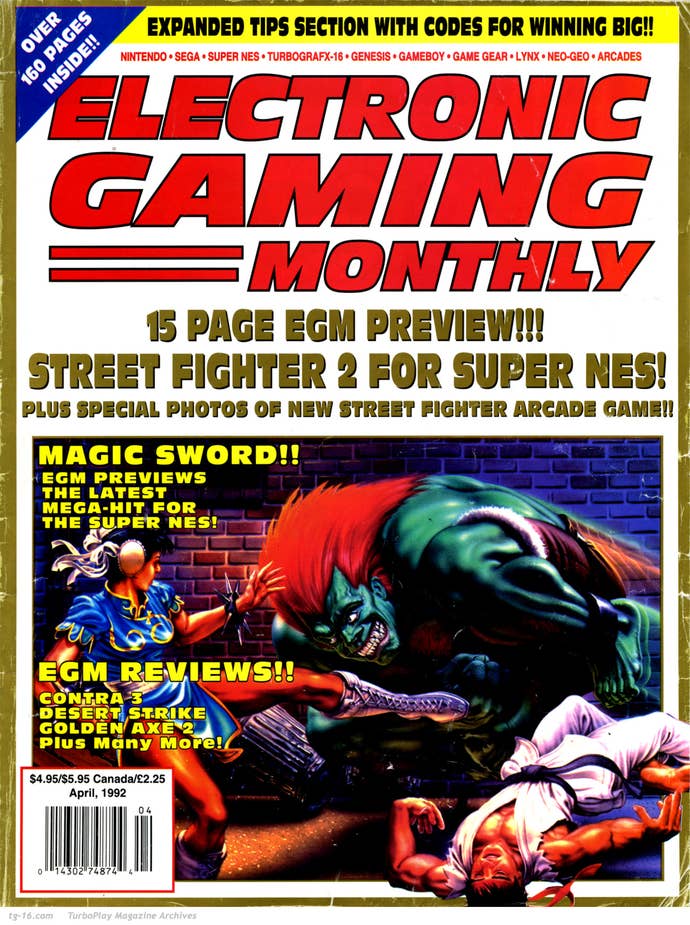

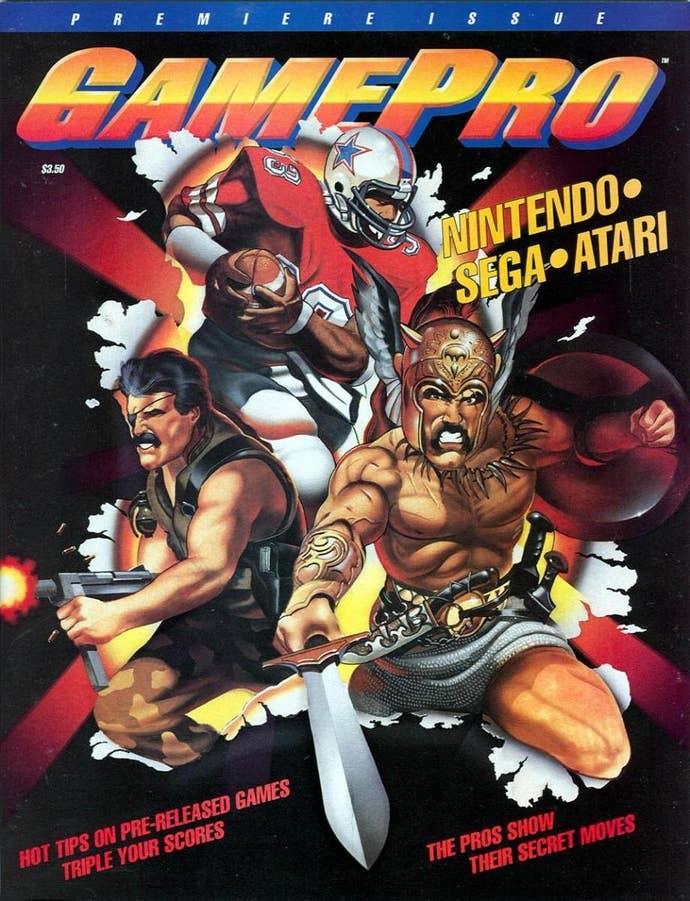

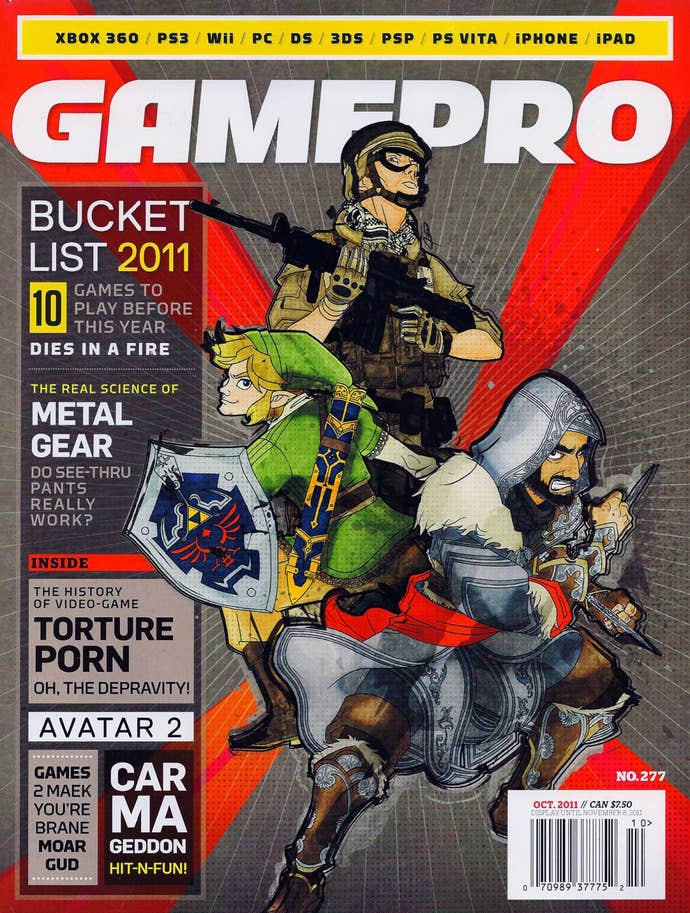

While Europe was seeing an explosion in evolution one video game magazines, in the States, the opposite was happening. Following the devastating crash of the video games market in 1983, most magazines had closed shop in the wake of marketing spending falling to an almost absolute zero. EG magazine had gone bi-monthly to try to weather the storm, but ended up going out of business in 1985 (although it did eventually have a second run of issues between '92 and '95). The only survivor of the 18 magazines that had been launched pre-crash was Computer Gaming World. However, US publications began to re-appear during the mid to late 80’s, and by the end of the decade were back to full strength, thanks to the likes of Gamepro, Nintendo Power and Electronic Games Monthly.

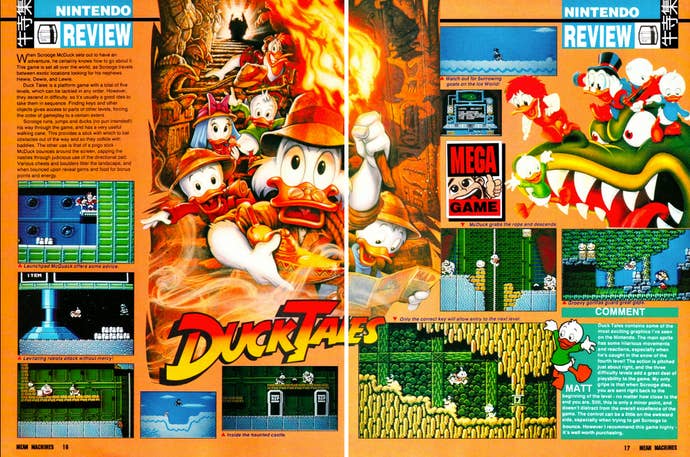

While the US publishing market picked up the pieces, over in Europe, magazines were flourishing, and their hyperbolic nature had continued to escalate, leading to what sometimes felt like min-maxing of the verbiage used in good and bad reviews. Great games were received with copious praise, whereas poor games were lambasted with language you simply didn’t see echoed across the pond – and indeed don't see written in gaming publications today (but funnily enough, you do often hear spoken by pundits on YouTube – but more about that later). British magazines like Your Sinclair, Amiga Power, and Mean Machines are all examples of publications that pushed the boundaries of humor and reviewing parlance.

Part of the reason why so many magazines in Europe were able to develop their editorial humor to such a degree was simply that the way magazines are published there enabled them to do so. All across Europe, magazine distribution is exceptionally well run and efficient, and popular magazines can literally sell out their entire print run thanks to targeted sales locations and very tight distribution patterns. In the states, distribution was far slower, almost completely untargeted, and far less efficient. At best, publishers could expect to sell around a third of the magazines they printed, and the rest were lost or dumped when they didn’t sell.

What this meant was European magazines could make a profit just by news-stand sales alone, while American magazines were essentially printing three magazines just so they could sell one – and that meant that newsstand profits didn't exist.

Subscriptions were far more popular in the States, but even then, their traditional low cost meant that subscription sales were break even, and not a profit center. Where revenue was generated was in advertising – so as long as a magazine had ads, it was viable. Ads were a source of revenue in Europe too, but they were less important than in the states. Because of that, there was far less pressure put on reviewers and writers when it came to negative coverage of games – because losing ads here and there didn't drastically affect the bottom line; it was considered par for the course to occasionally p**s off a publisher/advertiser with poor coverage.

In the US, however, there was far more nervousness about upsetting publishers, because pulled ads put a magazine's bottom line in jeopardy. This resulted in a tempering of language – or simply not covering a game if its coverage would be controversial.

This made some European mags feel more “honest,” simply because there was a perception that writers could say whatever they wanted. However, while this say-what-you-think style helped allude to a feeling of freedom of speech, US magazines were no less honest – they were simply more conservative in their praise and criticism. This did change a little as the 90’s rolled around, and magazines like Gamepro and EGM began to read a little more European-like in their rhetoric. However, the extreme language tended to be used more for the positive than the negative, and the specter of pulled advertising meant that editorial teams still often ran into business and management issues when it came to publishing severely critical pieces.

The Rise of Digital Publishing

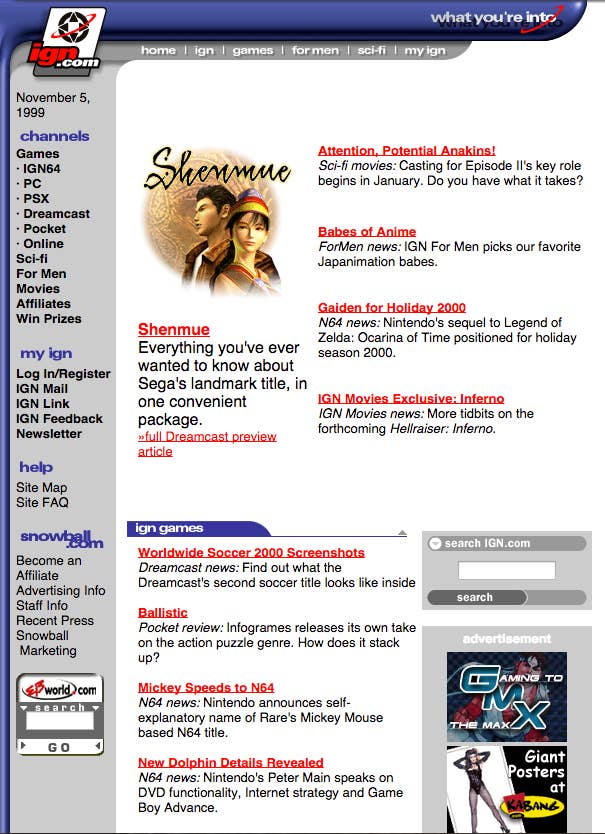

As the 90's wore on, something new emerged – the Internet. The first dedicated gaming web site was launched in November 1994, when print fanzine Game Zero became an online concern. Over the next few years, other small companies launched gaming websites, and major publishing companies, many of whom trepidatiously stepped into this new online publishing world with no idea just how important their websites would eventually become, soon joined them.

In those early days, working on a website wasn't necessarily seen as a prestigious thing, and speaking from first-hand experience, many of the most junior writers at publishing companies were given the reigns to these emergent websites. I was at IGN in 1997 – although wouldn't be called that for another couple of years – and that was most certainly the case for most of the team I managed. Because of this, early Internet writing was seen as haphazard and somewhat amateurish.

The reason for this was that magazines were on a long monthly cycle, and had generally larger, more experienced teams that included Managing and Executive editors who scrutinized pages and ensured that what was printed was as clear and error-free as possible. Not so online, where an often-punishing daily schedule emphasized speed and quantity over quality. This isn’t to disparage online writers – after all, I was one during this period – but cranking out news stories, reviews, tips and whatever else was being published required working far faster and far more prolifically than producing magazine content. Generally speaking, it was self-published work, and as such, far more mistakes were seen, which resulted in the perception that online writing was inferior to print.

However, as we've seen before, consumers are often prepared to put up with a "lesser" product if it's more interesting and convenient than another, and in the case of online, the speed at which information was disseminated was often weeks ahead of print. Slowly, but surely as the millennium turned over, we began to see a dramatic migration of readers out of the traditional print publications to online. While the effects wouldn't truly kick in until the late 00's, the turn of the century was the turning point for magazines. Any publication that didn't have a parallel online publication was in deep trouble.

The Impact of Community Comments

Another major thing happened during this era that would change the nature of online journalism considerably – community commenting. In the early days of the Internet – hard though it is to remember – there was no community commenting. It wasn't until the early 00's when forums and the rise of article-specific commentary began to appear, and that had a huge effect on the way writers wrote.

Before that point, their word was largely gospel. While readers would certainly write in to magazines to give feedback, it required pen, paper and a stamp to do so. That small effort provided a fairly large filter for comments,– simply because throwaway knee-jerk reactions would seem less compelling when someone wrote them out – assuming their words even made it to paper. And even then, comments received by publications were essentially private. Sure, almost every publication printed letters, but they picked and chose what to publish. Ultimately, reader feedback was largely benign and unthreatening.

Online comments, however, were open to everyone – and required almost no effort to write. All of a sudden writers were exposed to every possible opinion from every kind of gamer, from superfans who very likely knew more about the game than the reviewer did, to those who might pick apart the way something was written.

Suddenly, anyone writing particularly vehemently about any topic could become a target for online rage. No matter what your opinion, there was almost always somebody out in the ether who might feel aggravated or enraged by what was said – and the nature of online commenting meant that with just a few keystrokes, they could vent their anger with ease. This had a profound effect on writing. All of a sudden, journalists had to temper their comments, and think about what they were writing far more deeply than they had on magazines. That's not to say magazine writing is thoughtless – far from it. But there was a degree of tempering and self-censorship that went into online writing to ensure that the writer said what he or she wanted to say, but not in a way that would become a lightning rod to their readership.

Some may disagree with my assessment of how community commenting changed games journalism, and there are always exceptions to the rule, but for the most part, I believe the rise of community commenting did have an effect on many writers and what they wrote – and not necessarily a negative one. Sure, community comments themselves can be a nightmare, but the realization that people were watching and scrutinizing what was being written ensured that writers paid more attention to what they said, and indeed how they said it.

New Games Journalism

Another influential change to games journalism came in 2004 when British journalist Kieron Gillen wrote a post on his blog about new games journalism. Here, he essentially challenged the status quo, and talked about New Journalism applied to video game writing.

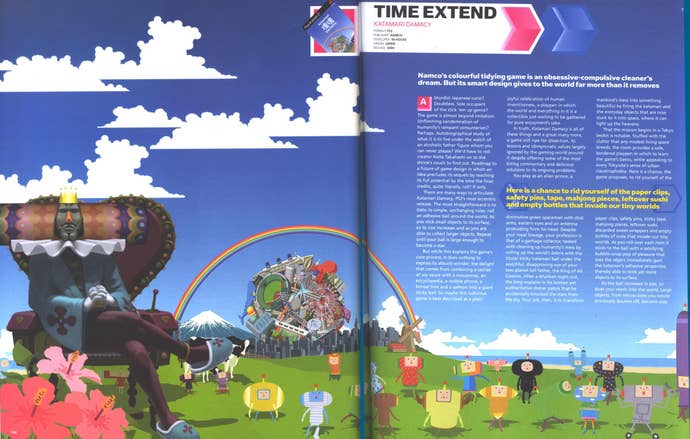

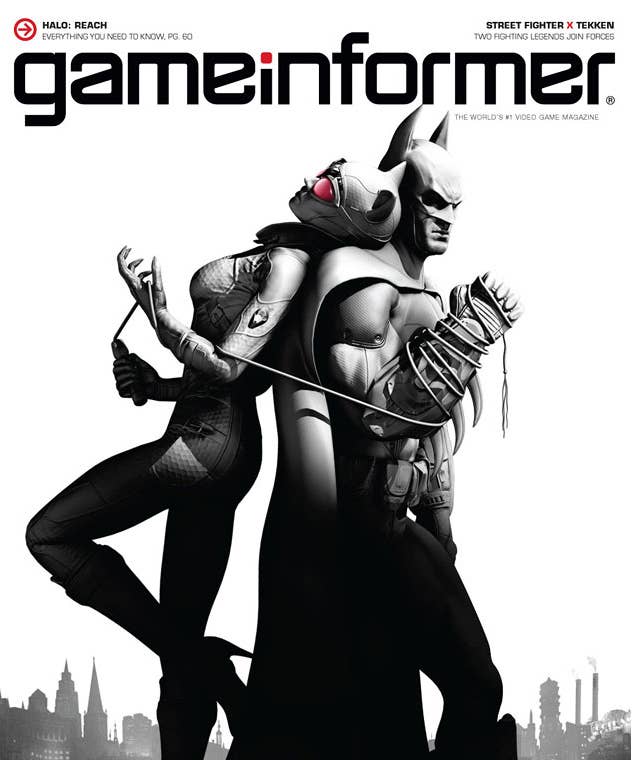

It was an interesting piece, and one that resonated particularly with "quality" gaming sites and magazines who wanted to move beyond the rather stale two-decade-old standard established in the early days of games journalism, and elevate games writing to something more erudite and worthy. Not all sites changed their tone, but we did see the rise of a generation of new journalists who wrote deeper, more thoughtful pieces in magazines like PC Gamer and Edge, and later, we'd see more academic writing on the likes of 1UP, Polygon and Grantland.

The Rise of YouTube and Twitch

The cycle of games coverage evolution has continued in recent years with the rise of YouTube and Twitch. This is the most significant challenge to the status quo since the advent of the Internet.

In the same way that "real gamers" changed the style and tone of coverage during games journalism's early years, so too are the new breed of "influencers" – gamers who've taken to YouTube and Twitch to cover games on a digital video format.

These new media folk essentially filled a gap that was not being effectively addressed by major publishers – very personal, specialized, or non-traditional takes on video gaming on digital video format. More importantly, they also provided an alternative form of gaming information consumption for younger gamers who were less interested in reading the mostly text output of the traditional press, and instead wanted to watch and listen to people play and talk about games.

At this point, it goes without saying that as a viewership number, the influencers on YouTube and Twitch now command an audience far larger than that of the more traditional gaming press. Just how much of an impact this will have on the publishing landscape remains to be seen. Most large publishers have their own YouTube material now, and some are extremely successful – but the fact of the matter is that a new, younger generation of gamers is growing up watching video games and video gaming information, and are less interested in reading about it.

What that means over the long term is a probable shakeout of the traditional media. YouTube and Twitch viewerships already dwarf the readers of old-school gaming media, and games publishers are now spending just as much time courting influencers as they are gaming journalists. That's not going to affect coverage too much, but what will is marketing spending. The traditional gaming press is essentially supported by advertising and marketing dollars from publishers – as it always has been – but if that support begins to be pulled in favor of spending money with influencers, or because it's seen as not worth it, that will have a radical effect on the current publishing landscape.

The interesting thing is that the influencers don't necessarily play by the same rules or follow the same standards as the traditional gaming media. There have already been examples of paid coverage of product by major influencers, and they're not always up-front about their editorial standards, and the nature of their coverage. That's understandable, since they're not journalists by trade, and indeed their viewership mightn't necessarily care about that, but the fact that most traditional outlets follow a published set of standards is something that essentially sets them apart from influencers.

Ultimately, regardless of official standards or lack thereof, I think however games journalism, and indeed the new breed of influencers evolve, it's critical that whatever is said or written is underpinned by full disclosure, so that viewers and readers know exactly what it is that they're watching or reading. That way it's clear whether the coverage being provided is independent, paid for – or whatever muddied waters lie in between.