Rat skewers and hagfish: the real-world history behind Dishonored’s disgusting food

Like our meaty, needy bodies in the real world, many video game characters have to eat or drink to replenish their health.

When you eat a weird mushroom that saps your hit points or drink wine that messes up your vision, you learn important (and sometimes painful) rules. But food does more than teach you about logic and systems – it’s also a critical part of worldbuilding. Virtual food can be a mouthwatering experience: delicious home-cooked meals in Breath of the Wild, unreasonably photogenic snacks in Final Fantasy 15, and hearty Skyrim fare: baked potatoes, wheels of cheese – there’s even taffy.

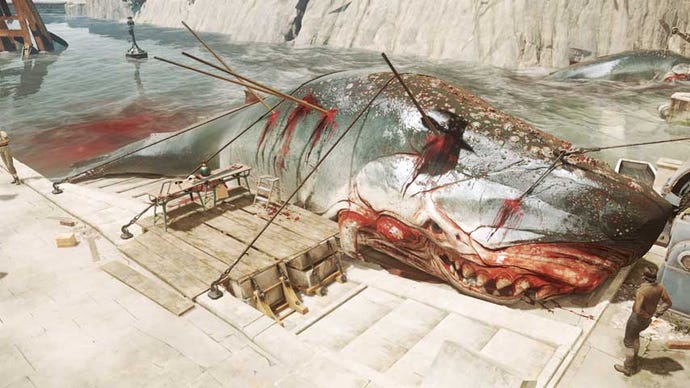

Then there’s Dishonored, which offers the player a veritable smorgasbord of industrial-grade misery: Pratchett’s jellied eels, potted Dabovka whale meat, rotten fruit, and rat skewers. Tapping into the raw, primal power of your stomach, Arkane’s critically-acclaimed stealth series uses food to explore the social hierarchy in Dunwall and beyond, drawing historic inspiration from famines, plagues, and food technology of the past.

“If you’re trying to imagine a new world, food is an excellent starting point,” narrative designer Sophie Mallinson tells me. Before working on Dishonored: Death of the Outsider, Mallinson spent her time at university studying the intersection of food and video games. “Where does food grow? Is it imported from other cities or nations? In Dishonored, players only need to look at a bowl of fruit to understand that each island exports their native crops. How is food distributed? Do people eat socially? Who gets to eat out of boredom rather than hunger, and what do they eat?”

Inspired by London and Edinburgh, Dunwall’s grimy alleys, cobblestoned streets, and lack of sanitation reflect a certain period in history when things were, quite frankly, pretty gross. The city is often described in Victorian terms – an era marked by a rising middle class, moralism, religious fervor, and cholera. It was also a time when big changes in commerce – particularly food – affected the lives of working-class Victorians.

In both Dishonored games, cities are littered with adverts for Pratchett’s Warehouses, Rothwild Whale Meat, and Padilla bottled sodas; many items you pick up are canned or rotten, and Dunwall denizens head to taverns and pubs rather than eat at home. “Though we tend to think the Victorians always cooked, industrialisation changed massively how and what the Victorians ate,” Dr. Ana Vadillo, Director of the MA Victorian Studies program at Birkbeck at the University of London, explains. “Many working-class women did not know how to cook. As the empire became more powerful, the market included foreign products. It was the period of cookery books and also of food advertising.” In Dunwall, foreign imports included fruit (hello, Tyvian pears) and new tastes from Karnaca. What we consider edible is a matter of class, culture, and context.

As a port, Dunwall’s foodscape is rich not only in whale meat but hagfish, a predatory species that lurk in its waters. Real-life hagfish are considered a delicacy in some parts of the world, and utterly repugnant in others; they’re somewhere between a worm and a fish, with rows of sharp teeth and a slimy protective coat. Mallinson points out that lobster – a luxury for many – used to be a peasant food. “Caviar used to be given away for free,” she says. “It’s not uncommon for rich people to appropriate grotesque foods as a status symbol.” According to Dr. Vadillo, “One typical [Victorian working-class] food was stout and oysters – oysters, however, became an upper-class food towards the end of the nineteenth century when they became scarce.” Jellied eels – once a staple in working-class cockney diets – remain a divisive part of modern-day UK’s pie and mash shops, although the tradition is dying out.

Back then, “working class” had different levels of nuance. “The nineteenth-century working-class was a very broad structure of society,” Dr. Vadillo explains, referring to categories established by the Victorian sociologist Charles Booth. “Some were ‘comfortable’, others were ‘poor’, or ‘very poor’, or ‘in chronic want’, or the lowest class, ‘semi-criminal’... that made a huge difference: you may eat oyster pie or, if in chronic want, just dirty bread. Malnutrition was typical.” Frequent sightings of rotten fruit in Dunwall line up with Dr. Vadillo’s description of a poverty-stricken diet: “potato pairings and more often than not rotten vegetables.” Dark loaves are common, as well as the occasional fancy flatbread hiding in cupboards.

Indeed, Arkane’s food choices reflect a form of socioeconomic storytelling that few games have attempted. “While dockyard workers survive on a diet of bread and canned whale meat, the upper-class eat hagfish eggs and eyes as a demonstration of their wealth, and serve their guests exotic animals on a silver platter,” Mallinson tells me. “In the Dunwall of the future, rat skewers will probably be found in fancy restaurants as a novelty dish, nodding sarcastically to a time when the homeless had no choice but to eat rats in the middle of a plague.” Guards frequently complain of hunger while they’re on patrol, which makes it almost a blessing when you choke them out and drag them into a dumpster.

But one of Dishonored’s most formative influences goes beyond trade and class conflict, and straight to the heart of a catastrophic agricultural blight. According to Dishonored 2 narrative designer Sachka Duval, the original Dishonored team was heavily inspired by the Great Irish Famine, which lasted from 1845 to 1849. This was a defining moment in European history that crippled commerce, culture, population growth, and industry not just in Ireland, but across the continent. “It caused mass Irish migrations to big urban centres like London and Manchester,” said Dr. Vadillo. “Many would live and die in poverty in the slums.”

While the Dishonored series borrows historical flavor from ages past, Duval reminds us that it’s still a game very much about the present, recalling how the games’ food were an expression of class, society, and exploitation. “I also remember writing an ambient dialogue for guards where they were commenting on aristocrats throwing food in the sea from the Duke’s balcony just for fun while people were starving in the streets, and all the waste and unfairness going on in the country,” she says. “We didn’t especially research the Victorian era for [Dishonored 2], as the message was always meant to be about today’s world. A political message is always more digestible... with some fictional dressing.”

Much like real life, Dishonored’s elite classes are physically insulated from the struggles of the working poor – kitchens are the realm of the working class. “The upper classes would obviously have cooks, and there was never a lack of food,” Dr. Vadillo says.

Across the series, kitchens retain a palpable sense of life that you can’t find in bedrooms, sitting rooms, or long, empty hallways – personally, during gameplay, I always felt guilty if I had to knock out a chef or cook’s assistant, because they were obviously just doing a job. “The kitchen is a bustling hub where servants come and go, and because the master of the house rarely sets foot in there, it can also be a sanctuary,” Mallinson explains, referring to the Tyvian opera singer Shan Yun’s manor in a wealthy Karnacan district. “I like to think of the kitchens in Dishonored as joyous places, where working-class families fill their hungry bellies, and where housemaids can relax and gossip at the end of the day.”

Though technology has given us the illusion that we’ve moved past this sort of class divide, one thing seems unanimously clear: mystery meat was an unfortunate part of life in Dishonored as well as the Victorian era. “How much meat one ate depended on money: a working-class family on a decent salary might eat meat or fish once or twice a week,” Dr. Vadillo says. ”Dickens often remarked it was unclear what kind of meat was eaten in some homes.” And in terms of mystery meat, it seems that one Dishonored creation will remain maddeningly elusive.

“I honestly can’t tell you with confidence what that is,” Mallinson says of the game’s biggest gastronomic enigma. “Let’s just call it a mystery!”

To celebrate 20 years of Arkane Studios, why not read about how Dark Messiah became the blueprint for Dishonored.