How hearing became the most important sense in the modern FPS

Do you hear that? The distant noise of Wilhelm screams and creaking doors. It’s the sound of audio departments taking over. For too long, they’ve all had the same, deeply ironic problem: nobody listens to them. But now, in the FPS genre, sound has become a central part of design.

“Audio has matured,” says Crytek audio director Florian Füsslin. “Before, we were more like the flavour and the ambience. Now we can really transport the player into the world. It’s very detailed and you can read it.”

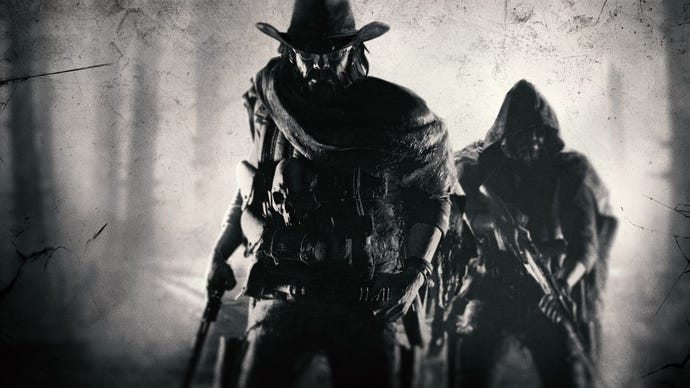

What Füsslin means is that sound can be information, and in competitive shooters, information is everything. If you have an idea of where your opponent is coming from, or what they intend to do next, you can counter with a plan of your own. For players of Crytek’s Hunt: Showdown, Ubisoft's Rainbow Six Siege, or even Modern Warfare’s Gunfight mode, close listening has become a powerful tool.

“We’ve been basically depriving the player of information in the game,” Crytek lead designer Dennis Schwarz says. In Hunt: Showdown, you enter a map with up to 12 other players - but unlike in a conventional battle royale, you can never be sure of how many are left. “You have to build up this mental map of what’s going on around you. Because of the deprival of information in other areas, sound has stepped up to deliver it.”

"While Hunt was designed with silent stealth in mind, the community discovered that noise could keep them alive too, by scaring off opponents"

A seasoned Hunt player is like one of its formidable bosses: a spider sitting in the centre of a web of audio cues, waiting for prey to betray its location. The giveaway could be any number of sounds: the flapping of a flock of crows disturbed by footsteps, or the whinny of a horse alarmed by a passing hunter. Experts learn to distinguish the groan of an old door from that of an armoured zombie husk, and the crack of a nearby branch from that of a distant rifle.

You can find the same principles at work in Rainbow Six Siege, albeit on a much smaller scale. Noticing the telltale sound of a drill can save you from the grenade salvo about to erupt through a wall, while the distinct whine of a drone tells you to be wary of spies. The best players can even identify a specific enemy operator from the sound of their gun alone, and prepare their defence accordingly. But this rich soundboard of gadget identification wasn’t something Ubisoft intended from the beginning.

“Siege has had a very long development process and went through a number of iterations,” Ubisoft Montréal sound designer Adam Tiller tells me. After the cancellation of Rainbow Six: Patriots, Ubisoft left the bloated and blustery shooter campaigns of the ‘00s behind and boiled the series down to maps centered around single buildings. In these cramped environs, where line-of-sight is rare, they discovered that listening took on new importance.

“It was perhaps not planned for, but revealed itself very early as being a facet we could capitalise on,” Tiller says. “Of course, as sound designers, we are happy to capitalise on any excuse to put more emphasis on the sound.”

In the years since, the Siege team’s approach to gadget noise has shifted from “cool sounds to accompany cool visuals” and become more useful to players. Designers provide the audio team with details on the dimensions, electronic workings and physical materials that gadgets are made from. Consequently, they all make distinct and recognisable sounds when used. “Without the validation of the community I am sceptical that we would be so daring as to make sound-centric designs,” Tiller says.

The Hunt team, too, saw its sound design embraced early by players. Crytek added clanking generators and loud gramophones that hunters could activate to cover their approach during an ambush. What they didn’t anticipate was that these environmental noise-makers would also be used to intimidate enemies. While Hunt was designed with silent stealth in mind, the community discovered that noise could keep them alive too, by scaring off opponents.

“In our internal testing, it was mostly about cautious movement,” Schwarz recalls. “But then we were seeing players just rampaging through the map, headshotting everything and asking for more.”

Crytek has developed tools that allow hunters to mess with the hearing of other players - like the chaos bomb, which can be hurled 20 or 30 metres and simulates the noise of a gunfight. And then there are the lower-tech methods enabled by Hunt’s systems: shooting at distant crows with a silenced gun, for an instance, giving rivals a false reading of where you are. The game has developed a meta based entirely within the mental map provided by sound.

“Sound is one of those things that I think most of us, as humans, don’t really pay much attention to,” Tiller says. “When we make a game, we are starting from scratch. We have to manually recreate all of those little sound cues that you might not notice in your daily routine. But they’re absolutely critical in giving your brain a complete picture of the world that surrounds you.”

If other shooter studios want to keep up, they should listen closely.