"He's on fire!": How a club bouncer starred in the making of billion-dollar arcade hit NBA Jam

The strangest thing happened to Willie Morris, Jr. Back in early 1992, when he was tearing up the courts of Chicago by day and bouncing a club by night, Morris was cooling off after a pickup game when a man introduced himself. He was making a video game about basketball, and he liked the way Morris played. He wanted to put him in the game. Morris thought he was joking.

But a few days later, on the invitation of Mark Turmell, Morris stood inside a warehouse rented out by Midway. He had to wear a generic blue and white uniform for his new gig. His playing surface would have nothing in common with the hardwood at the University of Illinois at Chicago where Turmell found him, or the outdoor courts where his stylish moves made him a local streetball hero.

Instead, he walked onto a looming blue backdrop. On set, his spectators would consist of hot lights and an elaborate network of cameras and computers. Morris would spend that afternoon and many more to come performing basketball drills — every possible move the NBA Jam crew could capture. His coaches consisted of Midway staffers like Turmell and video artist John Carlton.

Standing on a taped marker in the shape of an asterisk, Morris faced the camera and dribbled steadily. On a cue, he turned from one taped line to another, dribbling the same way at a new angle. He rotated his body again and dribbled a third time, then a fourth, repeating the maneuver until Midway had enough footage to simulate Morris dribbling in 360 degrees.

Morris played an entire game against an invisible opponent. He pretended to shoot, steal, pass, and block. He did layups and jump shots. He collapsed onto a gym mat like he had been pushed hard. In order for NBA Jam to boast a sense of realism, gamers had to perform the same motions as an actual basketball player. At 6′5″ and 198 pounds, Morris’s frame gave him the prototypical body for the average NBA player. In fact, in Midway’s big pitch to the NBA, it was four versions of Morris who stood in for the Jordans and Barkleys.

Like everyone else in Chicago (except Mark Turmell), Morris was a huge fan of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. Because of his marvelous moves, he earned the nickname “Air” Morris, just like his favorite player. Like Air Jordan, Air Morris knew how to get creative.

Once the Midway team finished up the fundamentals, they moved on to dunks. Using a lowered hoop as his target, Morris launched himself off a ramp over and over, attempting one highlight reel moment after another. He did the double-clutch, where he gripped the ball with both palms and pumped it into the goal; the tomahawk, where he chopped the ball in with one arm; and the windmill, where he lifted the ball up mid-air as if he was moving it from one shelf up to another.

“Let’s see something different,” said John Carlton. Morris took off, sitting on an invisible chair for a split second. Then, he jammed the ball in backwards. For another move, he spun his body mid-dunk as if his arms were helicopter blades, ending the rotation with a monster slam. Morris kept going, adding different angles and gestures, and Midway kept filming.

To accommodate for the differences in pro players, NBA Jam required both black and white skin tones, and a few body types. Turmell recruited three more amateur or college players: Todd McClearn, Tony Scott, and Stephen Howard.

Like Morris, Howard met Turmell after a pickup game. A small forward with a successful playing career at DePaul University, Howard was freshly graduated and hoped to pick up an NBA contract in the fall. As a gamer, Howard recognized the Midway name and liked Turmell’s vision. Howard said yes, convincing Turmell to pay him a little extra since he was going to be a real NBA player soon, too.

Howard spent hours in the studio repeating simple poses and waiting to perform. At times, the work got monotonous. But when he had the opportunity to do something big, like a somersault dunk off a picnic table, Howard understood just how cool this game could be. Those weekend blue screen sessions laid the foundation for NBA Jam.

Assembling a development team at Midway was a process based on the project’s needs and the employees’ personal tastes alike. Turmell checked around the office to see who was available. Across 1992, a core team of seven built NBA Jam:

- Mark Turmell, lead designer

- Shawn Liptak, programmer

- Jamie Rivett, programmer

- John Carlton, artist

- Tony Goskie, artist

- Sal DiVita, artist

- Jon Hey, music supervisor

Roles shifted through development, and other Midway developers pitched in. Early in the process, artist and Joust creator John Newcomer taught Turmell the digitization techniques he learned while making High Impact Football, but Newcomer wasn’t involved in the long-term development of NBA Jam.

While Newcomer brought a coin-op veteran’s perspective to the project, Sal DiVita was brand new to video games. A twentysomething a few years younger than Turmell, DiVita always had a knack for drawing. A Chicago native, DiVita grew up hoping to create oil paintings for book covers and movie posters. But in the late 80s, DiVita discovered the Amiga 2000, a personal computer that allowed him to create 3D art. Turning his newfound skills into a job, he worked at a company making educational tapes with his art school friend Tony Goskie. After Goskie left the tapes company and got a job at Midway, he encouraged DiVita to apply and join him. They worked alongside one another again on NBA Jam.

Creative oversight at Midway was minimal. As long as a team could deliver a sellable game on a tight deadline, management left imaginations free to roam. Some members of the NBA Jam team were basketball fans while others never watched. Some had worked with Turmell before while others hadn’t. Some expected the game to strive for realism while others were more open to interpretation. There was no shortage of skills or opinions to go around. If the game shipped early, the team would earn a twenty percent royalty bonus.

Hi-8 tape of the blue screen sessions in hand, Carlton and Goskie processed the footage on computers, then snipped the best takes and stripped the actors from the background frame by frame. While the blue background gave them great tonal range while filming, putting blue uniforms on that background was a bad decision. Cleaning up the images was a time-consuming process; having to manually remove and adjust the tiny blue pixels clinging to the actors’ outlines made it take forever.

After that, the artists isolated sections of the jerseys and created “slots” that filled with a team’s colors on command. The palette swapping technique saved both memory and time; Mortal Kombat had used it to great effect. Customizing each team’s uniform down to its logos and details was not possible, so each duo was instead differentiated by a color combination. When the Seattle SuperSonics were picked, the slots filled with green and yellow; for the Phoenix Suns, purple and orange; for the Orlando Magic, black and blue; and so on.

NBA Jam’s graphics benefited from top-shelf tech. While competitors used sixteen palettes of sixteen colors for their games, Midway’s hardware provided room for 256 palettes of 256 colors, creating a lush range of shades. Turmell encouraged his artists to intensifying the brightness of the jerseys until the colors popped.

Once their bodies were sorted out, the original studio actors’ heads were removed from their necks and replaced by a digital “object attach” point. As with the jerseys, different head and body combinations could seamlessly produce playable NBA characters in seconds. Turmell and sound designer Jon Hey picked the lineups, using box scores, articles, and intuition to determine which two-man squads would best represent each team. On a Team Select screen, each pro would come to be represented by a portrait, a last name, and four attributes. Although not all of their original choices were approved by the NBA (most notably, Michael Jordan), the game’s final roll call was stacked.

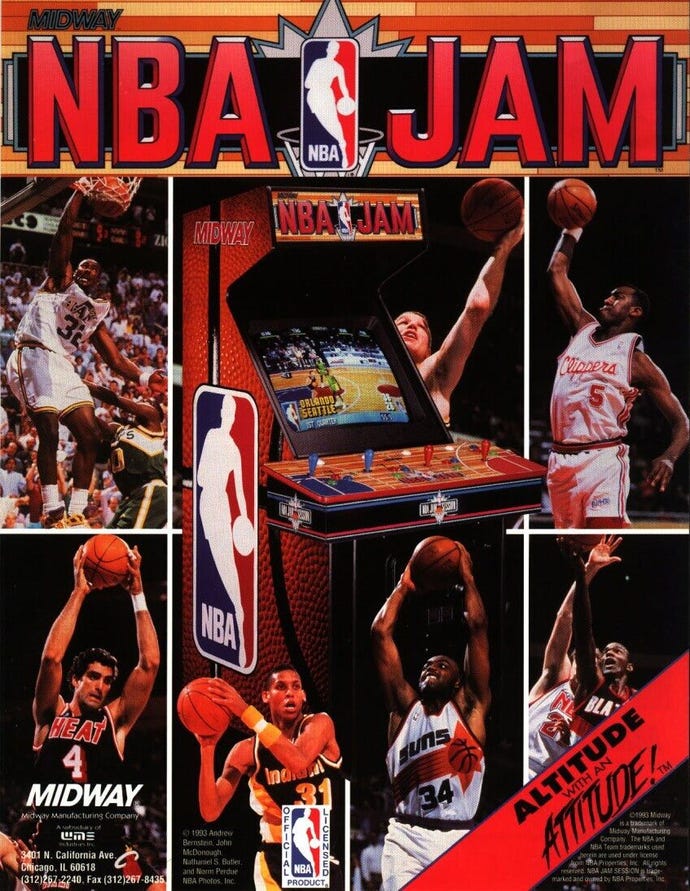

Unlike other basketball games that had mere flashes of name-brand talent, NBA Jam’s 54-player roster was stuffed with the era’s hottest stars. Drawing from the 1992 to 1993 season, it seemed like everyone was in there: Charles Barkley, Hakeem Olajuwon, Scottie Pippen, Shawn Kemp, Karl Malone, John Stockton, Dominique Wilkins, Reggie Miller, Glen Rice, Larry Johnson, David Robinson, James Worthy, Tim Hardaway, Shaquille O’Neal. NBA Jam would feature 37 former, present, and future All-Stars, including three-quarters of the Dream Team. Superstardom was just a couple of quarters away.

The artist responsible for drawing every in-game head was Tony Goskie. Armed with the program Deluxe Paint, Goskie had to do it all by hand. Since the NBA supplied Midway with only face-on shots, Goskie had to extrapolate photos and video stills to draw each of the eleven angles required of every player head. The task was even more labor-intensive than extracting the actors from the tape. Goskie spent two painstaking months just drawing the heads.

There was also the matter of designing the battleground. DePaul University granted Midway access to its basketball court, so Goskie headed over with a camera and shot footage from the stands. On his computer, he compiled a row of still frames into a panorama of a court, then digitally painted the whole thing into the game. The hardwood, the hoops, the backboard, the scorer’s table: It all turned to pixels. Goskie gave NBA Jam court a blue and red scheme as a nod to both the DePaul Blue Demons and Turmell’s beloved Detroit Pistons. Once the court was made, he grabbed video of real-life basketball spectators and painted the fans into the game, animating them so they reacted to NBA Jam’s on-court happenings appropriately. A few familiar Midway faces made it into the audience, too; Goskie himself can be spotted on the left baseline, thoughtfully stroking his chin.

In another touch of authenticity, boards along the sidelines changed ads between periods. Midway wanted to use the same sponsors as NBA television broadcasts, but the league didn’t want to leverage any trademarks it didn’t own. As a result, the team came up with its own sponsors. NBA Jam was brought to you by the likes of Tortorice’s Pizzeria (a real local pizza chain), Air Morris sneakers (a fake shoe brand), Cheer-Accident (the indie rock band Mortal Kombat sound designer Dan Forden played in), and the inevitable Mortal Kombat II.

This is an excerpt from NBA Jam by Reyan Ali, published by Boss Fight Books. You can order a copy direct from the publisher here in print and digital formats.

NBA Jam is also available on Amazon Kindle and you can follow NBA Jam on Twitter.