"I spent my everything. I broke." - Tetsuya Mizuguchi on burnout and creating the "new-wow"

One of the first things Tetsuya Mizuguchi - creator of psychedelic on-rails shooter Rez - showed at his Reboot Develop presentation was a painting of Moscow. The abstract artwork from Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky sees the metropolis rendered as an otherworldly-yet-recognisable smudge.

Kandinsky is famous for having synesthesia, a sensory quirk that means he could see colours and sounds, associating them with other concepts: for example, he saw yellow as middle C on a brass trumpet, and he believed the colour black signified closure. The painting imagined the noise of the city rising as paint streaks, a transient heat haze. The sun swirled above like a golden vortex.

“In this industry, we can create anything,” Mizuguchi says.

The Japanese developer’s first video game creation was 29 years ago, working at Sega in his first ever games job. It was a Sega Game Gear - a handheld system from the console manufacturer - that he had rigged to strap to his face. A DIY VR kit. Nobody asked him to make it, but he took it into a board meeting anyway, where it was promptly ignored. This was in 1991.

Three years later, Mizuguchi was working on his first ever game: Sega Rally Championship. The small team had never worked on a 3D game before and yet they created this fully-fledged racing game for arcades, featuring different traction values for various surfaces, and with a mechanised car that twisted and turned while the players fought against force-feedback from the steering wheel.

There’s a clear throughline to Mizuguchi’s work - it’s all connected. The Japanese developer isn’t satisfied with you feeling just one thing while playing his games - he wants you to experience something completely new, something that takes over multiple senses at once. He wants to recreate what it’s like to have synesthesia.

With Rez, his first music-based game, every homing projectile you fire breaks off and becomes a piece of the soundtrack, laser beams forming into the rat-tat of percussion.

“Why? Why do people feel the groove?” Mizuguchi asks. “If you want to create that kind of feel, you have to know. Maybe we have a beat, you know, a heartbeat. I think this is a basic instinct. I don’t have all the answers, but naturally we have the beat. You have the beat,” he says, pointing to my chest, “and maybe we have some synchronisation. And if we play drums together, maybe in just ten seconds, twenty seconds, we can synchronise. This is the ability of all humans. Even children - any human being can connect through music. This is a big thing.”

Music is a universal language, of course. It doesn’t matter what culture you come from, each has a rich musical history that’s unique to its geography and invented instruments. As we’ve become a global planet, these genres have combined, creating offshoots and collaborations. A synchronicity, all of us connected by that beat.

“I want to create a new experience, using new technology,” Mizuguchi explains. “I think a video game is one of the best forms to create a kind of sensory experience. I got a lot of inspiration from music and music videos - music videos are audio and visuals combined to create a new narrative. It’s a great form, but it’s passive. It’s an outside of the box experience. So we have daily experiences in life and we know this is life, or this is a real thing. New types of experiences make you go, ‘Wow, what is this?’ It’s a fun moment for the player, but it’s also a fun moment for the designer. Designing those experiences was impossible, but now it’s becoming possible using new tech. It’s a new era. We are moving towards an experiential era.”

Mizuguchi is, of course, talking about the dawn of convincing virtual reality, where the world can melt away and we can truly inhabit these alien places. Before VR was where it is now, Mizuguchi felt creatively stifled by flat television screens. It was this limitation that led him to leave games in 2011 after wrapping up work on Kinect music game Child of Eden, at which point he began teaching at a Japanese university instead.

“I couldn’t make a game after this for four years because I didn’t want to make any games with 2D anymore,” he explains. “It’s very unusual and unnatural. Why does the 2D flat screen exist in our life? Our world, all the time, all things are 3D. If you’re a game designer and you imagine something, in your mind it’s this 3D image. All the time, I’m dreaming - in Rez, Child of Eden - that something comes from,” he throws a hand past his face, “here. But we need to squeeze all of this into a 2D flat space.

“I spent all my passion and energy on Child of Eden. I spent my everything. I broke. The project was amazing, but after that project, I burned out. Also, I felt this was a limit. I couldn’t move forward. I had no imagination [left] for the existing technology - 2D flat. Even with Kinect, you’re playing facing the monitor, but it’s small and 2D. I’m playing like this,” he waves his arms, “but I’m watching a small window. I felt kind of ambivalent. All the time I’m imagining something flying here, or hearing some sounds from here, and like this - the freedom. I needed to stop.”

Mizuguchi says teaching allowed him to see his life in retrospect, tracing it backwards. He learned things from his students and could see his games career from a different perspective. When the Oculus Rift was announced, everything fell into place. He was ready to create something entirely new, though by first looking backwards once more to one of his most popular games: Rez.

“When I made Rez the first time, I struggled with frustration and regret. In my mind, the game is like this,” he gestures widely. “But in reality it’s like this,” he makes a small rectangle with his fingers. “And it was really tough. The first Rez was a rail shooter - you can’t move freely. But Rez Infinite’s Area X finally had free movement and the technology makes that. Our frustration is getting less.”

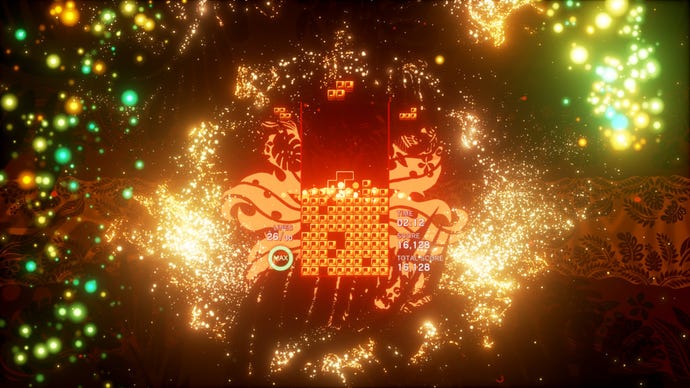

Since then, he’s also made Tetris Effect for PSVR, reimagining one of the most perfect games that ever existed as an experiential, synesthesiac experience with pulsing blocks and 3D effects jumping in and out of the screen as each movement enhances the music. It can feel like a religious experience, temporarily transforming you out of your fleshy existence into this space where all that matters is the zone. It’s undeniably powerful and it even makes some people cry the first time they experience it.

“It’s because it creates a new emotional chemistry through new stimulations,” Mizuguchi explains. “It’s not fake, it’s an acceptable reality. This is the big ability of the human, we have creativity. VR is just the beginning. It’s a door to much more gorgeous experiential art. I’m dreaming more. We want to make the new-good feel, the new-good zone, and the flow states. We have that feeling inside, but we don’t know how, so this is a new area. I’m just thinking about the next game. This is an ‘our life’ theme. How can we enhance experiences? We create the new experiences with sound, maybe some haptic. What is the new-wow?”