Far Cry 5 review - the best the series has been since 2012

Ever since Far Cry 3, Ubisoft’s open-world series has been about the bad guys. These charismatic antagonists take top billing on the box art, and they taunt you across the entire adventure. Next to your protagonist - who’s usually as likeable as a men’s rights activist - they bleed personality.

Far Cry 5 takes this formula to its natural conclusion: now there are four antagonists and the main character is a fully customisable mute. Hooray!

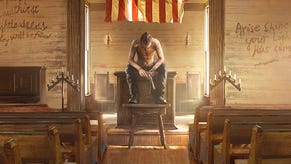

As an unnamed deputy, you head to Hope County, Montana, to arrest an enigmatic cult leader known as Joseph Seed. The Seed family run a religious group called the Project at Eden’s Gate and have laid siege to rural America, rounding up civilians, torturing, and maiming - all in the name of God. Hallelujah.

Of course, the arrest goes awry, fulfilling a prophecy Joseph predicted and embedding the cult’s beliefs - martyring Joseph without killing him. Radio contact is cut off from the outside world, you are alone, and Hope County has completed its transformation into Fascist Fields.

Hope County is split into three regions - the Henbane River, Holland Valley, and Whitetail Mountains - and each of these regions is overseen by one of Joseph’s trusted advisors: John Seed lords over Holland Valley, Faith Seed enraptures the Henbane River region, and Jacob Seed instills fear into the people of Whitetail Mountains.

" Weapons have a real impact to them, and guns recoil like a bucking bull - every shot is angry and physical."

Each of the Eden’s Gate leaders has their own methods: John Seed is the cult’s lawyer and rules by intimidation, Faith Seed controls the population through a drug called Bliss, and Jacob Seed recruits frontline soldiers by culling the weak. Only you and your star-spangled assault rifle, your canine companion, a couple of bears, a cougar, resistance fighters, your wingsuit, some air support, a garage full of vehicles, a flamethrower, a bow, lots of explosives, and a combine harvester can stop them.

These multiple antagonists represent a structural shift for Far Cry 5. On the tutorial island, an NPC asks you to climb a radio tower. When you reach the peak, he explains that you don’t need to worry - he won’t have you climbing towers all over Montana. Instead of unlocking the world by clambering up vantage points, you discover points of interest by simply exploring: drive past a cult outpost and it will be on your map forever; talk to a rescued civilian and they might point you to a sidequest; free companions and they will offer up more activities.

Far Cry 5 is still as stuffed with things to do as other Ubisoft games, but it never feels overwhelming because of the way it unfurls. There are no progress gates, and you can spread your time between the three regions as you wish. Everything you do - be it stealing a fuel truck, burning a Bliss field, saving citizens, doing side missions, or taking on one of the more lengthy story quests - it all feeds into a progress bar for the antagonist of that region.

Each of the Seeds must be drawn out by messing with their operations, every third of the bar triggering a big story mission. When I played Far Cry 5 at preview, I wasn’t sold on this structure. It felt confusing and I ended up doing a lot of the filler missions instead of getting to the meat during my short playtime. In the context of the full game, however, it works - even if it can be a bit grindy as you slowly plug away at filling the final third of each bar.

Mission quality varies, but the good outweighs the bad. Stealing bull testicles as Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing plays over the action is a highlight. Fighting a demon moose who has been pumped full of drugs is not.

Luckily, the core of the game feels stronger than ever. Weapons have a real impact to them, and guns recoil like a bucking bull - every shot is angry and physical. There’s just enough auto-aim snap on console to make you feel like a sharpshooter as well, whether you are flipping between targets in an outpost or sailing down a zipline with an uzi, gunning down cultists as you go.

Likewise, vehicles feel great to drive. You can get behind the wheel of a big rig and smash through roadblocks, or you can speed across dirt roads in a muscle car, its back-end fishtailing angrily with every push of the accelerator. Once you are done with the roads, you can take to the skies in helicopters and aeroplanes, strafing compounds and performing bombing runs. Or you can jetski and boat across the Henbane River.

All three regions have their own distinct personality, too. For example, the Henbane River region is difficult to traverse by car because it’s so hilly and the river itself divides the landmasses like a liquid artery. Take to the air and it comes into its own. Holland Valley, meanwhile, is best explored on four wheels, smashing through fields and barreling into cows. The unpredictability of the world keeps things fresh.

"There are some surprising bits of social commentary nestled in among the stereotypical hillbillies, survivalists, righteous priests, and alien hunters."

Spreading fire is as much a part of Far Cry’s identity as bad guys gurning into the camera, because fire is indiscriminate.

Far Cry smashes loads of components together, placing warring factions, animals, and the elements into the map and letting you manipulate them all. Far Cry 5 hasn’t done much to improve the series here - other than let you play the entire thing with a co-op buddy, upping the unpredictability - but watching your plans unfold as you become the AI puppetmaster is as intoxicating as ever. At least until you are almost murdered by a turkey.

Tonally, Far Cry 5 is a strange game. There is no getting away from the real world climate it released in. Here you are, saving the northwestern US from a cult of Christian extremists, diplomacy fails within the first five minutes, and the only answer to all of your problems is a gun.

In the lead up to release, Ubisoft made it clear that Far Cry 5 had no political statement to make, but there is no escaping the context it released in. Despite those apolitical claims, some of the dialogue is overtly political, too, though probably not in the way you might expect.

At one point, one of the cult leaders breaks into a monologue about their motives, asking you if you’ve seen the way the world is, if you’ve seen who is in charge, if you’ve seen the wars, if you have seen the walls being erected. Far Cry 5 does have a message, and that message appears to be: the world has gone to s**t, and people act desperate when pushed, particularly if they have embedded belief systems.

There’s also a lot of hand-wringing about violence and how you are as bad as the cultists for resorting to murder to solve Hope County’s issues. It’s a bit cliche, but there are some surprising bits of social commentary nestled in among the stereotypical hillbillies, survivalists, righteous priests, and alien hunters. I just wish there was more of it.

Ubisoft did lots of research to make sure Eden’s Gate has a believable cult structure, but it’s not explored enough in-game. I wouldn’t even know John Seed was a lawyer if I hadn’t read the information elsewhere. Despite being the main attraction, the bad guys just don’t get enough screen time.

Still, Far Cry 5 is an interesting game to play in 2018, and it’s easily the best the series has been since Vaas asked us if we knew the definition of insanity in 2012. Also, I’m well into religious music (and Marvin Gaye) now.