2013 in Review: Tomb Raider Makes Us Ask, Do We Have to Kill a Classic in Order to Save It?

Square Enix updated Lara Croft for the modern age of games, but the end result barely resembles Tomb Raider as we knew it.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

About an hour and a half into Tomb Raider, not long after young protagonist Lara Croft is forced to kill a man for the first time in a desperate act of self-defense, she stumbles into an ambush.

"Light her up!" screams an unseen antagonist, blinding her with a flood lamp as six or seven men take aim and open fire. Lara survives, of course, or else it wouldn't be a very long game; she clears the entire room with deadly force.

This style of shootout -- one young woman against half a dozen gun-toting thugs (or more) -- is repeated over and over again throughout the entirety of Tomb Raider. Like her new inspiration Nathan Drake, Lara is forced into racking up a disproportionately enormous body count over the course of her adventure, wiping out entire hit squads of goons at a time.

That's par for the course in contemporary games, especially those gunning (literally) to take a bite from Uncharted's format. But it feels bizarre in the context of a Tomb Raider game, even one coming after Crystal Dynamics' previous attempts to reboot Tomb Raider, Legend and Underworld. In the course of surviving that single ambush beneath the spotlight glare, Lara guns down more people than she killed in the entirety of the 1996 game that launched the Tomb Raider series.

No, really. Think back to the original Tomb Raider and, if the cobwebs of your memory haven't obscured the details, you'll recall that Lara Croft's debut outing saw her enter armed conflict with a total of five humans. Not only that, each had a name: Larson, Jerome, the Kid, Pierre, and the Cowboy. There were no faceless mooks to kill in waves, and whenever you had to deal with several henchmen at once it made for a difficult and harrowing challenge. Each encounter with human characters in 1996's Tomb Raider proved to be memorable and significant, and every one represented a key moment in Lara's adventure.

Despite this paucity of human targets, Tomb Raider '96 wasn't short on combat. Lara took on any number of creatures both mundane and mystical throughout her journey, from bats and wolves to the bizarre skinless humanoid monstrosities of Atlantis, and of course the infamous earth-shaking T-rex. (Even Lara's nemesis, Jacqueline Natla, turned out not to be truly human herself.) Lara collected quite a number of weapons during her adventure, and players found plenty of opportunities to put them to use.

Yet no sensible person would ever call Tomb Raider '96 a shooter. It had shooting, yes, but that didn't define the game. Those encounters, whether with humans or wildlife encountered along the way, acted as punctuation. They existed to liven up Lara's journey, whose essence was about exploration, not combat. The original Tomb Raider saw players navigating complex labyrinths, navigating ancient traps and puzzles, and picking her way though a vast underground space in search of answers to an ancient mystery.

On its surface, the new Tomb Raider seems much the same. But the balance is skewed, and the game's elements exist in very different proportions. Lara engages in nearly as much combat as she does exploration, and the traversal aspect of the adventure feels greatly stripped down. Where some found Tomb Raider '96 dull because of all the wall-climbing in solitary caverns it entailed, the reboot's crime is in making the act of exploration nearly non-existent -- boring in its simplicity. The game text makes a cheeky reference to "tomb raiding," which after all these years comes off as a little too self-conscious for its own good (like when Star Trek finally referenced its own title three decades after its debut). The irony, though, is that no other game in the franchise has contained less of its namesake tomb-raiding than this year's. Quite the contrary; Crystal Dynamics quarantined anything resembling the cave-diving of yore into optional "tomb challenges," carefully sealing away the need for any skill besides those revolving around combat neatly out of sight.

Don't be afraid, they reassured players. Those scary parts where you're not killing things can't hurt you anymore.

2013's Tomb Raider, as its barebones title implies, essentially relaunches the entire series. With this game, Crystal Dynamics and Square Enix/Eidos have wiped Lara's slate clean, reworking her origin to conspicuously ignore the childhood flashbacks of previous games. And why not? It's not like the existing Lara Croft canon is any great shakes; what plot existed in the earliest games was only there to offer players the most minimal excuse to go spelunking in ancient ruins. Reboots are all the rage these days as intellectual property holders try to wring a little more life from their brands without forcing mass audiences to worry particulars like backstory, continuity, or history.

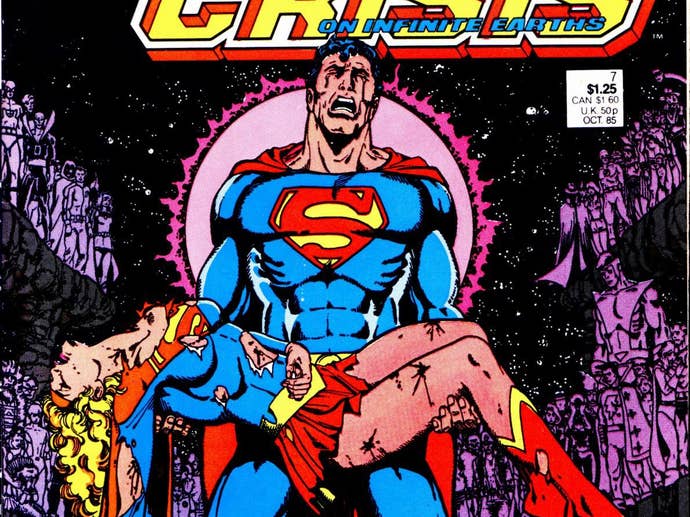

You can probably credit (or blame) DC Comics for the concept of rebooting; they came up with it back in the '80s when they realized they could no longer reconcile four or five decades of goofy superhero stories with the more serious plots they wanted to tell. So, they hit the reset button on their universe and let everything start from scratch. Now relaunches are a handy way to preserve the things most people can connect to about a franchise -- generally characters and settings -- without being bogged down by all the baggage of the past.

But where Crisis on Infinite Earths led to a number of genuinely thoughtful new takes on the DC Universe, including Batman: Year One and John Byrne's run on Superman, contemporary reboots tend to be less about clearing the way for fresh, nuanced stories than about retelling the same old stories in a flashier way. Sony Pictures, for instance, appears to have relaunched Spider-man a mere decade later so they can recycle not only villains but also individual scenes. The aforementioned Star Trek franchise went back in time to radically change its series' backstory... only to put all the pieces back where you expect them, but this time with more lasers and less characterization.

Lowering barriers to entry is the watchword of contemporary large-scale pop culture, even as the tremendous success of intricate works like Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones demonstrate a thirst for complex, serialized narratives. But those are "premium" shows -- read "niche." To really soak up maximum dollars (instead of merely a whole lot of dollars), IP holders have to break things down to their most easily digestible form, which has translated in practice to constant reboots and endless retellings of the same iconic tales.

Tomb Raider slots neatly into this trend. Here we have a new origin story for Lara Croft, which is totally unlike the previous origin stories of Lara Croft, yet ends up creating the same Lara Croft we used to know (except less cartoonish in appearance, and much grimier). And it all makes for a pretty damn solid game; it simply stinks at being Tomb Raider.

Don't get me wrong; my complaints are no rose-tinted lamentation against change. By no means were the old school Tomb Raiders perfect; there's a reason Crystal Dynamics has essentially reinvented the franchise twice now, and it's not because they simply had nothing better to do with their time. Tomb Raider '96 was a product of its era, and that era was nearly 20 years ago. The original game could get away with presenting the exploration of 3D spaces as its main hook, because 3D spaces that you could actually explore were so exciting and new in 1996. These days, we're over it. A few developers still somehow know how to sell us on the thrill of wandering around big video game worlds -- mostly Bethesda -- but for the most part it would take a special kind of game to work like Tomb Raider did in 1996 and still excite us.

And that's even assuming you were to modernize the game's fundamental mechanics. Tomb Raider, seen through 17 years of hindsight, is almost comically boxy and unfathomably clumsy by the standards of 2013. Truth be told, it was too unwieldy to work even a few years after its debut, though that didn't stop Core Designs and Eidos from rehashing the same dated engine annually for five years until the formerly impressive sales of Lara Croft's adventures took a dive off a steep cliff and the franchise fell into a tragic cycle of trailing into obsolescence and playing catch-up with the competitors it helped inspire.

Tomb Raider 2013 couldn't play like Tomb Raider 1996; not if it was to exist outside of gaming's niches, anyway. Crystal Dynamics already tried modernizing the original Tomb Raider, quite literally, in the form of Tomb Raider: Anniversary. It sold decently, but nowhere near what Square Enix and Eidos aspire to. They have blockbuster ambitions for the franchise; could the world's only video game series that can claim to have caught the attention of Douglas Copland, U2, and Angelina Jolie settle for anything less? The rules of blockbuster games, unfortunately, have grown fairly rigid and painfully stifling. Sure, there are exceptions, but for every Minecraft that did its own thing in its own way and hit big, you have a dozen Brinks or Vanquishes that did their own things in their own way and flopped. To play with the big kids, developers know you have to play like the big kids.

The reality of video games is that even the most popular ideas have a shelf life. How many franchises from 15 years ago remain vital today? Those that remain active have almost universally reinvented themselves. Castlevania is barely recognizable in its current form; Metal Gear looks like Splinter Cell and vice-versa; Half-Life proves that absence makes the heart grow fonder; and even evergreen Mario and Zelda seem to have lost their shine. Final Fantasy's sales and ratings have dropped sharply this past generation; meanwhile, Bravely Default (a direct sequel in all but name to Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light) has won over hearts who otherwise sneer at Final Fantasy by simply filing off its original branding.

The new Tomb Raider bears only a superficial resemblance to its ancestor. As someone who enjoyed the older games' sense of exploration and discovery (made to feel all the more profound through the sparing use of musical cues), I found the new game intensely frustrating for abandoning so much of what drew me to the franchise in the first place. And yet, I find myself at a loss to suggest how it could have been anything different without relegating itself to near-irrelevance in this boom-or-bust market.

Do we have to kill a classic series in order to save it? Tomb Raider suggests yes. But let's not forget, our corporate overlords do have an alternative: They could let a good idea fade gracefully rather than beating every last drop of blood from its mangled, mutant carcass. I realize business operates on the principles of profit rather than class, but playing for integrity can pay off, too. In the coming year, I wouldn't mind seeing a few faltering favorites actively retired -- if not forever, then at least until someone has a genuinely great idea to revitalize it. There's no shame in admitting that the best place for a classic just might be in the past.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)

.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)