2013 in Review: The State of Video Game History and Preservation

How has the year treated the games of eras gone by? Jeremy and Pete look at 2013’s news of the old.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Time and technology march ever onward, and with it march video games. Nevertheless, you can't really appreciate where you're going without having clear perspective on where you've been, which makes the preservation of video game history an essential pursuit. The great thing about game history is that it isn't simply valuable as information -- old games can still be a lot of fun on their own, too.

With 2013 ushering in a new generation of consoles, how fares the industry's ability to keep alive an archive of its past?

Jeremy Parish: In my opinion? Not so well.

I've already lamented the lack of backward compatibility in this year's new consoles several times here within the confines of USgamer. I'll say it again, though: It's a huge loss to everyone. On a practical front, it means PlayStation 4 and Xbox One are the first new systems in more than a decade to be completely limited to playing their specific libraries. The last time that happened was in 2001, when Microsoft launched the first Xbox and had no library to be backward compatible with, and Nintendo's GameCube marked a switch from cartridges to optical discs. Since then, BC has been something we take for granted in our new systems. I guess you really don't love what you have until it's gone.

There is some hope on the horizon in the form of PlayStation 4's Gaikai streaming, which recently resurfaced after completely vanishing from the public eye for nearly a year. But we've yet to see just how close Sony manages to come to its promise of streaming access to the entirety of 15 years of PlayStation. As anyone who has tried playing marquee PSP titles like Crisis Core and Mega Man: Powered Up on Vita knows -- not to mention anyone who's seen personal favorites delisted from PSN and Nintendo's Virtual Console -- publisher apathy and the tangled web of intellectual rights that surround games can really do a number on the availability of content on digital platforms. As we've seen with Netflix, when content vanishes from a streaming service, it's simply gone.

Gaming's overall move toward digital distribution and heavily locked-down software rights makes sense from a business perspective, and it's definitely a convenience for gamers in the short term. In the long-term, however -- the long view taken by game preservationists -- the new generation of games seems hopeless ephemeral. How can we enshrine the medium in museums if the content is lorded over by publishers? You can put a plastic baggie with Richard Garriott's home-produced Ultima predecessor Akalabeth in a display case, because it's a tangible physical object, but what about something like Hohokum for PS4?

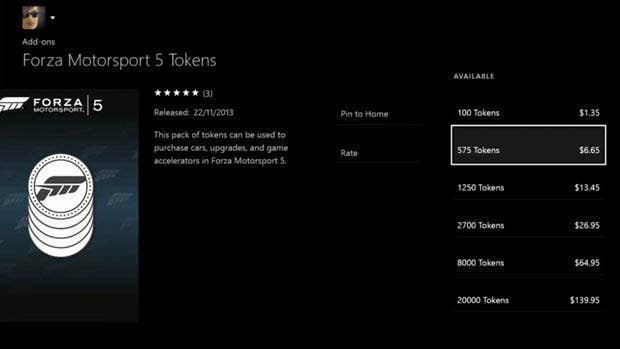

The preservation of digital platform-exclusive titles hinges on the cooperation and interest of publishers, and if there's anyone in the world that doesn't care about canonizing the medium's history, it's publishers. Even Nintendo, which makes a lively business of repurposing of its back catalog, has yet to make a single one of its classic arcade games available in any form. If not for the secondhand arcade cabinet market, there would be no way to experience landmark creation Donkey Kong in its original form save piracy. And that's a cornerstone game from a publisher that actually acknowledges the past! Imagine how much worse it could be 20 years from now when trying to preserve something like Crimson Dragon, a digital-only title published by the willfully apathetic Microsoft. Even if it's not a particularly good game, it's still a significant release with a considerable legacy behind it -- precisely the sort of thing that belongs in a museum. But even if we could somehow get it there, would it work properly decades from now with all those free-to-play-style e-commerce hooks and other online and social elements worked so thoroughly into its design?

Pete Davison: Jeremy, you nail my biggest hesitation with the looming "digital age" -- the fact that every time I purchase something digitally, there's a little voice in the back of my head that says "one day you might not be able to play this... are you okay with that?"

I actually go back and forth a bit on how I feel about this. With my Vita, I enjoy having a variety of PSP and Vita games at my fingertips without having to change cartridges. Oddly, I feel the opposite way about my 3DS, preferring physical packages when possible. On PC, I have no hesitation whatsoever buying something on Steam, GOG or via a bundle, yet on consoles I will always, without fail, buy a physical copy.

It's my personal dream that one day I'll have a "game room" with a selection of systems and shelves full of games from throughout the ages. Some of these systems I already own and have kept in good working order, others I intend to collect at some point in the future. For those I do already own, I still have the physical media containing the games I might want to play on them someday, and it's a simple matter of inserting the disk or cartridge and we're away. For the newer systems, however, I have to consider how much hard drive space they have, and whether I have a reliable, safe means of backing them up just in case the worst happens.

There are some that argue backwards compatibility and historical interest in the medium's development is largely irrelevant. But I'll still happily go back and play something like Gateway to Apshai in favor of the latest and greatest releases sometimes; while nostalgia doesn't always live up to your expectations, sometimes it can be enormously comforting, plus I find it endlessly fascinating to see how far the medium has come in such a relatively short space of time.

Jeremy: I love digital collections. I never buy retail copies of 3DS or Vita games if I can avoid it; my 3DS's SD card has something like 150 games on it that I can play at any time no matter where I am. But yeah, I realize I'm kind of taking my life into my own hands there, especially with Nintendo's so-called account "system."

But let's wrestle this back to game history and preservation. I saw a few noteworthy movements on that front in 2013, but none so impressive as M2's fantastic 3D Classics series for old Sega arcade and Genesis games. They've kind of picked up the torch that Nintendo and Arika dropped back in 2011 after porting over half a dozen NES games -- including a few complete duds like Urban Champion -- and as usual for M2's Sega preservation, it absolutely shames the emulation work anyone else in the industry is doing. Granted, M2 isn't doing anything super extreme like cycle-accurate emulation, but as a consumer product their arcade framework and "Giga Drive" emulator for Sega Genesis (which is built to support 3D technology in games never designed for it) are unparalleled. From Space Harrier to Sonic the Hedgehog, the 3D Classics are absolutely stupendous.

But it's not just the quality of the emulation itself that really impresses me. What I love most of all is M2's realization that video games aren't just pixels on a screen. Video games are experiences, and while it's not entirely possible to convert the intangible sensations of an old video game onto a new system, M2 does its best to reproduce the ephemera that made these classics so memorable. Whether simulating (and encouraging) the physical "lean" control system of Super Hang-On's special arcade cabinet or simulating the color bleed and CRT screen distortion that affected Genesis games on old televisions, M2 puts a tremendous amount of effort into ensuring each game they recreate feels as accurate as possible -- not just to the hardwired programming, but to the subjective human experience.

The downside, of course, is that this level of care means they can only handle a small number of games at any time. I wish there were a way to make that caliber of emulation more widespread... and that there were more profit in it.

Pete: Yes, I'm in 100% agreement there. There are a lot of these old arcade games for which the experience wasn't just what was happening on screen; it was in the physical controls, or the hydraulics-powered cabinet, or in the case of G-LOC, that amazing R-360 cabinet that actually went upside down when you looped the loop.

As you say, it's nigh-impossible to completely recreate these experiences on modern machines, but there are ways you can help capture that sort of atmosphere through special effects. And there's other ways that modern gaming can improve these experiences, too.

Microsoft's sadly defunct Game Room project on Xbox 360 had some good ideas going on, but also missed a few opportunities. I really liked the fact that as you bought games, you populated a virtual arcade with machines and could see avatars of friends and other players wandering around -- but I always felt a first-person option would have made that experience even better. Similarly, while the Airwolf-inspired music and ambient noise while you were browsing the menus was cool, it always felt oddly jarring that it abruptly stopped the moment you stepped up to a virtual machine -- having the option for that arcade atmosphere to continue in the background would have been pretty cool, I think.

One of the best things about Game Room, though, was how it gave us pixel-perfect recreations of old arcade, VCS and Intellivision games, but leveraged the power of modern online gaming to provide us with additional features like a real-time leaderboard that you could see yourself climbing as you played. For me, this was one of the best examples of "old meets new" -- the games themselves were intact in their original form, but the experience of crowding around an arcade machine with friends and competing for the top score was instead replaced by a global community of players all doing the same thing. It made games I already loved considerably more addictive in the process -- I can't tell you how many hours I sank into the Game Room version of Activision's River Raid, for example.

The reason this sort of value-added bonus is important, I think, is that it gives modern gamers an incentive to play these old games for more than curiosity's sake. If there's an element of online competition or social play, even the most dated game can get a new lease on life.

Jeremy: Yes, but what has it done for you lately? In the world of 2013, Game Room is a non-starter. And, in fact, most publishers have completely abandoned any attempt to treat game history with any respect. Sega's M2-programmed classic conversions are a beautiful but tragic exception to the rule -- tragic because no one else is making the effort. Nintendo's Virtual Console still exists, and the fact that it occasionally offers inexpensive versions insanely pricey software (EarthBound, Recca, and Shantae, to name three examples from the past few months) justifies its otherwise meager existence. But third party support for any back-catalog content has practically dried up; instead, the best we can hope for seems to be ugly, phoned-in (har har) mobile shovelware ports. Have you seen what Square Enix did to Dragon Quest? Heartbreaking.

There's more hope to be found on the PC side of things -- and not just for PC games. GOG.com's name has contracted even as the service has expanded its perview to encompass more than the good old games it formerly made its raison d'etre, but even so it continues to spoon out inexpensive renditions of DOS, Windows, and Mac classics reworked to run on modern operating systems.

Meanwhile, PC-based console emulators continue to expand the breadth and quality of their support, while the march of technology means the quest for emulation's holy grail -- cycle-perfect emulators -- creeps ever closer to fruition. There's also a thriving underground of handheld emulation devices, from the disastrous Neo Geo X to the more capable GCW Zero; none of these portable systems stand up to the best PC emulators, but they generally get the job done. I have high hopes for the Retron 5, due out early next year. Not only does it offer support for an unreasonable number of classic Nintendo and Sega systems, the manufacturer has promised to support the system with compatibility upgrades that can be downloaded and flashed to the system. So maybe notoriously finicky titles like Akumajou Densetsu (Castlevania III) and Star Fox won't work on day one, but there's a chance they will eventually.

The problem with all these emulators is that, with the exception of the Retron 5, they all hinge on piracy and the illegal distribution of ROMs. But that's all we can count on, because the industry continues to be so uninterested in offering legitimate access to history -- and what little effort they make is usually slapdash at best.

Pete: Yes, the Retron 5 has a lot of people excited. It'll be interesting to see how much of a success it will be, and whether or not it will prompt a change in attitudes towards classic game archival and preservation.

As you say, at present things look unfortunately bleak on the "official" front -- but at least, as ethically and legally questionable as it can be, we have the dedicated enthusiasts putting together comprehensive digital archives of ROMs and disk images for defunct systems. It's sad that, more often than not, we have to rely on strictly unofficial practices to enjoy the medium's heritage; it's something that I really think the industry as a whole needs to think more about as it continues to mature.