2013 in Review: In The Last of Us, No Death is Meaningless

Naughty Dog's The Last of Us is that rare thing in video games: an experience that gets us to think about the reasons behind all the inevitable violence.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The Last of Us is painful; an aggressively dire and miserable game to play.

Every moment that gets your blood up, that lets you thrill in that physical connection with a digital world, is followed by a crushing tenderness for its leads, Joel and Ellie. They're doomed and damned and destined for disappointment at every step, and even when they're at their most unlikable -- which, let's be honest, is most of the time with Joel -- you can't help but love them. The relationship they share is as tenuous as humanity's future in the post-infected world, where folks turn into ravenous, carnivorous mushrooms. Never really father and daughter, never really good friends; they're just survivors.

There are a lot of survivor stories, though, and plenty of them are about an adult and child trying to survive in a seemingly hopeless world. The Last of Us came not even half a year after Telltale Games wrapped up the first season of The Walking Dead, and the sad story of Clementine and Lee shares more than just cosmetic similarities with that of Joel and Ellie. So Naughty Dog told a familiar story. Why The Last of Us was one of 2013's very best games is the magnificent way in which they told it. They made it an action game about guns and then used that framework to answer video games' unanswerable question: How do you justify all that violence?

It's a question that Naughty Dog's needed to answer for years now, and not just in a post-apocalyptic game that asks you to care deeply about its characters. Uncharted, Naughty Dog's first PlayStation 3 game from 2007, was a success with a troubling cancer metastasizing deep in its belly from the start. That game did for adventure -- games where you explore strange places while scrambling all over its many nooks and crannies -- what Valve had done with Half-Life; it successfully rebuilt a familiar form of video game action for linear storytelling. The whole trilogy of Uncharted games thrived on a zesty blend of spices, one part likeable human character to two parts impossible set piece spectacle and a heaping spoonful of shooting.

That last ingredient was the problem, though. The more human Nate Drake seemed and the more glamorously wrought his adventures, the more irksome it became that he was killing so many people. The link between heroism and violence has always been troubling in video games, but the abstraction of older games made it easier to reconcile digital body count with games' mechanical nature. B.J. Blazkowicz shoots a thousand Nazis? Fine. He's barely more than a pair of eyebrows. Nathan Drake is a person, though. He moves like a man, talks like a man, and thanks to Nolan North's iconic performance every little aside that stumbles out of his mouth makes him sound like a man you know. But after the affable dude with the half-tuck kills his 900th henchman, there's an inevitable disconnect.

Every aspect of the game reinforces that negative association with violence. The balance between ambient noise and silence; the sick, susurrus noises of the infected, and the constant banging and shouting of firefights.

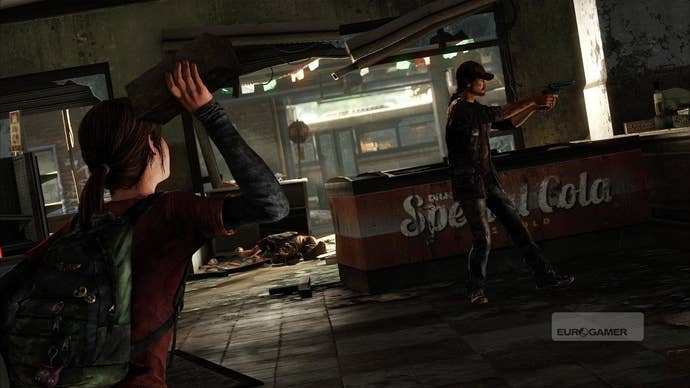

The Last of Us, as a machine, is made up of the same component parts as Uncharted. For the bulk of its 17 or so hours, you're guiding Joel in and around uneven, fairly constrained arenas that perpetually push him forward to a scripted set piece. Ancient ruins are replaced with modern ones, but they're mostly the same. Like Nate, Joel picks up the ammunition and tools he finds along the way. Fewer stockpiles of fresh grenades, more inexplicably un-scavenged bottles of rubbing alcohol, but also largely the same. In between the exploration and gathering, Nate and Joel both spend a lot of time shooting or bludgeoning people to death. Joel actually has a wider variety of options for committing violence. Screw just carrying one shotgun and a pistol, Mr. Drake. Joel's packing a rifle, a bow and arrow, a pistol, and a bunch of glass shivs for when a clicker gets squirrelly. The man keeps a stock of freaking pipe bombs packed with nails.

With Joel and Ellie, though, you never want to use these. Nate half-heartedly protests when he's handed a gun in Uncharted 2, but he treats every gun battle like a guy in a spin class. Uh oh, better lift those legs! What a workout! Violence is the basic reality of everyday life in The Last of Us, and playing the game, you can feel how desperate people are to avoid it, but how willing they are to kill if they have to survive. Whether slinking through the bowels of Salt Lake City trying to avoid the fungal remains of humanity, or facing off against a crew of cannibalistic desperados, it's always preferable to try and get through without making a fuss.

Every aspect of the game reinforces that negative association with violence. The balance between ambient noise and silence, the sick, susurrus noises of the infected, and then the constant banging and shouting of firefights all make you uncomfortable when a fight can happen. Even with your hefty arsenal, it's still all too easy to die. And whenever you get in a fight, you have less opportunity to listen to these characters actually talk to one another, and you want to. They're wonderfully acted and unpredictable. Getting to know who Joel's become in the years after the game's harrowing opening is more of a reward than putting a bullet in someone. Going in with guns blazing is an option, and you can get through fine, but it deprives you of the temporary peace that the game regularly rewards you with. An opportunity to look into someone's lost life in a Pittsburgh suburb; a chat with Ellie about what animals used to be like; a brief moment to feel like a person.

The Last of Us isn't a replicable game. Who would want it to be? As amazing as it is to walk in Joel and Ellie's shoes, it's not pleasurable in the traditional sense.

And the most amazing thing is that even though the game never lets you change the possible outcome, or change who these people are, it makes every single one of your actions as a player feel meaningful. By taking the care to avoid the miserable violence in the game, you feel fully in the role of both Joel and, eventually, Ellie. The choices the game gives you at every moment are limited but feel like full reflections of the characters you play as. Even in the game's absolutely punishing ending, the choices you're given never feel arbitrary or out of character. There's no disconnect.

The Last of Us isn't a replicable game. Who would want it to be? As amazing as it is to walk in Joel and Ellie's shoes, it's not pleasurable in the traditional sense. No one plays The Last of Us to unwind at the end of the day, so it's answer to the question of violence isn't a perfect one. Naughty Dog did manage to make one of the few games where violence is a centerpiece of the experience while also making every single instance of violence matter in the process. No death is meaningless in The Last of Us, and that makes living through its story all the more powerful.