1989: The Year Anime Invaded the US Games Business

Anime has always been a part of gaming, but for many years, US publishers felt its artistic style was too "Japanese" and alienating for a western audience. However, in 1989 a tipping point was reached - and anime finally started to become cool. Jeremy Parish explains why.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Clash at Demonhead is the first to make it off the beach

To judge Clash at Demonhead by its cover, you'd expect it to be your typical low-budget, 1980s, post-Flash-Gordon, sci-fi schlock: A muscular Rambo-looking dude in chromed armor fires lasers at an insectile skeleton-man and other strange monsters while what appears to be a space cheerleader shrinks timidly into his protective embrace. Real boilerplate, potboiler stuff.

And that is precisely why that old saw about judging works by their covers exists in the first place. Although the box of Clash at Demonhead actually does depict concepts from the game (the chrome guy is protagonist Billy "Bang" Blitz, the skeleton is apparent villain Tom Guycot, the mountain in the background is the locale in which the game action takes place), the in-game presentation couldn't be further from the straight-to-video, Mystery Science Theater 3000-fodder quality of the cover's airbrush job. If the box art begged to be splashed across the side of a stoner's van circa 1980, the in-game aesthetic would have been better suited a wall scroll at a mall kiosk a couple of decades later. It was 100% pure anime... a word most American gamers didn't even know at the time.

In a recent piece on Medium, Henk Rogers (the man who brought Tetris to the West and role-playing games to the East) discussed how his Wizardry-inspired Japan-only creation, The Black Onyx, presented itself to Japan with box art in the style of Frank Frazetta: "A hero standing on a pile of monsters swinging a sword. The problem was that in Japan nobody knew what the hell that meant," he recalled. Within a few years, sales of The Black Onyx were eclipsed by the likes of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy. Rogers admitted, "I realized that I didn’t quite understand the Japanese aesthetic and way. These games were quite different to mine, and just struck a more effective cultural chord."

Dragon Quest, of course, became a blow-out hit in Japan in large part because of its illustrations and character designs by Akira Toriyama, the cartoonist behind popular manga series Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball. The game didn't attract much attention until publisher Enix began promoting it in the pages of Shounen Jump, the weekly comic anthology where Toriyama's work appeared. Suddenly millions of kids took notice. The whimsy of Toriyama's illustrations didn't translate well to the game's miserable little map sprites, but once battle began players got to go mano-a-mano against colorful monsters straight from the pages of Toriyama's comics. And Dragon Quest was hardly unique; Japanese-developed games had drawn visual inspiration from manga and anime for as long as Japanese designers had been making games.

But Toriyama-style cartoons were as anathema to American audiences as Frazetta-esque fantasy paintings were to the Japanese. A cultural divide was at work, which made things difficult for Japanese publishers who hoped to peddle their distinctly Japanese-flavored video games in the U.S. as the '90s rolled around. In those days, anime in the West was confined to a small, fanatical group of animation connoisseurs. Anime would make inroads in the States before long thanks to the likes of Akira and Sailor Moon, but at the start of the '90s a video game publisher would sooner turn a box into an eyesore of bad art and inscrutable design than dare leave Japanese cartoons on the cover.

While cover art was easy to change, in-game visuals were a different matter altogether. Try as they might to scrub away any vestige of a foreign origin (especially a Japanese origin), publishers usually (but not always) found it easier just to make the cover more Western in style and leave the in-game contents untouched. Maybe they'd reprogram a rice ball to look like a hamburger; perhaps they'd change some names around; but ultimately they'd leave the distinctly Japanese aesthetic untouched.

Which brings us back to Clash at Demonhead, a textbook example of this phenomenon in action. By no means was Clash the first game whose origins its American publisher tried to half-heartedly whitewash, and it certainly wasn't the last, but it may well have been the most obvious.

Clash at Demonhead was not based on an existing animation or comic. Its Japanese title, Dengeki Big Bang!, doesn't correspond to any other property -- not even Media Works' Dengeki family of game and anime magazines, which began publishing a few years after Clash's release. But you'd never know it to look at the game; every inch of it is drenched in manga aesthetics. It feels completely like an authentic licensed property.

The game begins with comic panel-like story sequences in which Bang, an agent of a secret organization called S.A.B.R.E., is summoned from his vacation to rescue an abducted professor. Bang himself is a young hero in the '70s action anime mode, with big hair and distinguishing facial scars a la Harlock, and a can-do spirit of the type that would later be lampooned by more self-aware post-Evangelion anime like Martian Successor Nadesico. But more importantly, Clash perpetually bordered on complete zaniness, slipping freely between dramatic action and goofy pratfalls in the manner of true Osamu Tezuka devotees.

A surface reading of Clash at Demonhead might suggest a game that played like a more fanciful version of a James Bond spy tale, with the quest for a lost professor leading to a race to deactivate a planet-shattering doomsday device. Aside from the fact that Bang's nemeses took the form of bizarre, inhuman creatures (besides the skeletal Guycot, Bang also battled a raging panda, a mushroom person, and more), Clash's plot fell very much into the epic secret agent mold. Yet its whimsical, anime-influenced presentation took the edge off the drama, rendering it very much as a broad comedy with a few dramatic elements.

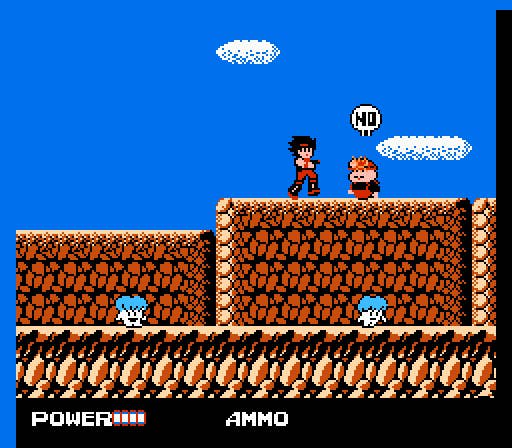

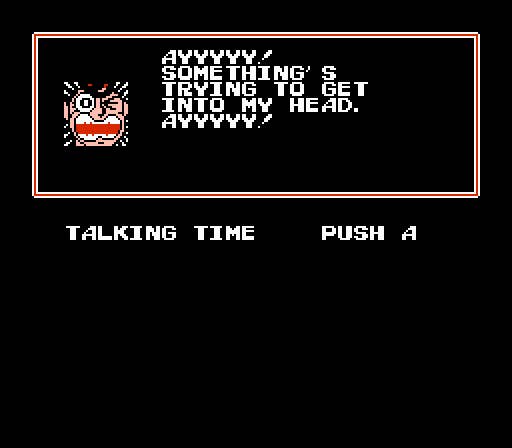

The wackiness frequently bled beyond the borders of the cutscenes and dialogue sequences (helpfully labelled as "TALKING TIME") and into the actual game mechanics. Shoot an ally character and they'd complain by way of a word balloon emblazoned with the word NO; return to where Bang's comrade was betrayed and murdered and the poor fellow's corpse would become progressively more decomposed (but cartoonishly so) with each visit. The plot's increasingly loopy twists and double-crosses went down more easily thanks to the fever delirium with which they were presented, and the loose, imperfect platforming shooting became a little easier to forgive because of the gung-ho style of the art and narrative.

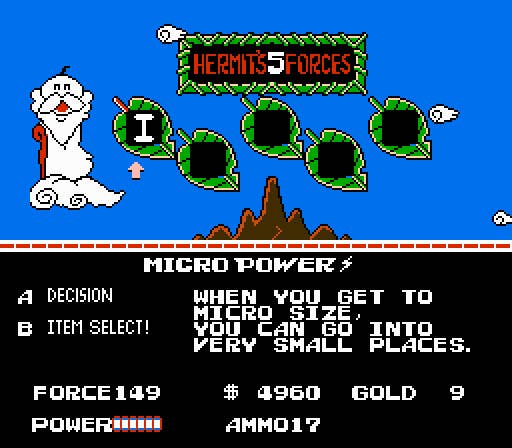

In a lot of ways, Clash was fairly ambitious for a platformer of its vintage. Its world sprawled across an expansive map of dozens of discrete stages linked by various routes, with Bang frequently forced to return to previously explored routes as dictated by the narrative or even to enter stages from a different direction in order to reach otherwise unaccessible areas. Bang could purchase weapons and tools to aid his exploration (the shopkeeper tended store with his tiny daughter by his side, a decidedly Toriyama-esque convention), and the boss encounters were each unique and inventive. It was a flawed game, no doubt, but an entertaining one.

Much of Clash at Demonhead's appeal came from its decidedly over-the-top manga influences, which gave the game a vital energy lacking in more serious NES contemporaries like Code Name: Viper or Top Secret Episode: Golgo 13 (which actually was based on a manga, but a far more straight-laced one). Thankfully, the snarling chrome-clad hero from the box had nothing to do with the reality of the game, which cheerfully paid homage to a school of slightly goofy Japanese cartoons that already was fading into obscurity.

American kids may not have understood the pastiche elements of Clash, but those who played it definitely responded to its hilarity (including Scott Pilgrim creator Bryan Lee O'Malley, whose work exhibits the same energetic, manga-influenced vibe as the game). Even more than today, publishers fretted back then about their packaging seeming too foreign, but they needn't have worried; slapstick insanity speaks its own universal language, and Clash at Demonhead's decidedly foreign personality turned it into a cult classic among players who didn't quite know what they were experiencing but who dug it anyway. The game certainly didn't single-handedly change American attitudes about foreign media, but it should be remembered as one more straw added to that particular camel's back.

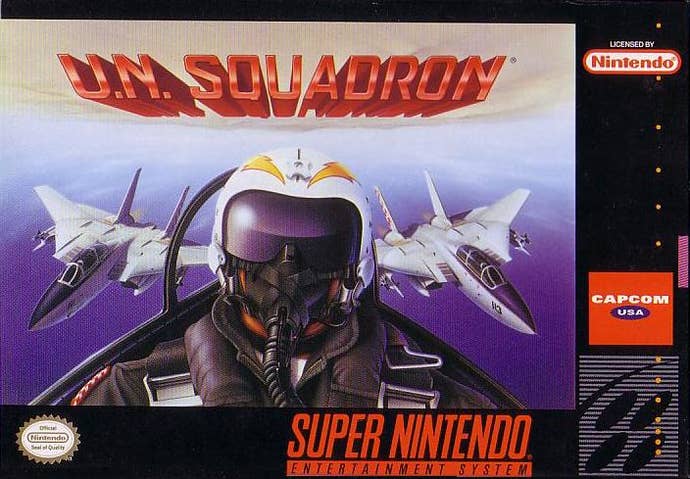

U.N. Squadron Sneaks in, Barely Disguised

In the grand pantheon of video games, not too many people remember Capcom's U.N. Squadron. It made a tiny ripple in the arcade and a somewhat more noticeable impact via its console conversion, thanks largely to being one of the first shooters on Super NES.

As shooters go, U.N. Squadron was pretty solid. It had that late '80s/early '90s Capcom vibe about it, which is to say that in addition to its excellent graphics and audio, it also offered a wealth of added features to give the button-mashing action some extra substance. Players could select one of three different protagonists -- the fast guy, the heavy-hitter, and the balanced generalist -- and, as usual for Capcom's action games, spend their combat earnings at the inter-level shop.

In many ways, U.N. Squadron felt like a variant on its sibling shooter 1943: The Battle of Midway turned sideways. Despite the difference in play style -- horizontal versus vertical -- it used a lot of the same tricks as its more popular counterpart. One-hit kills and multiple lives were deprecated in favor of a single red-gradiated life bar per credit, allowing a somewhat more generous (but nevertheless far from toothless) difficulty level than, say, Gradius or R-Type. It also allowed for two-person cooperative play, at least in the arcade.

U.N. Squadron didn't lack for spectacle. Dizzying formations of small fighters harassed the played en route to the enormous set piece boss. The boss encounters often broke from the fixed scrolling format, with players looping back and forth to dismantle massive enemy war machines. The stage three skirmish against a huge warship, for example, felt like a combination of 1943's aircraft carrier sequences and R-Type's battleship stage. The varied scenery kept things interesting, taking players high in the sky, over the water, into deep canyons, and more; so too did the shifting mission goals, such as clearing out enemy formations within a limited amount of time.

While the scenarios and bosses didn't always make sense -- was that Blackbird-style stealth fighter the size of the Spruce Goose really a logical feat of combat engineering? -- they certainly looked cool. So, too, did the players' choice of aircraft and their associated pilots; well, at least the dartlike F-20 Tigershark (flown by Shin Kazama, whose mop of hair all but obscured his vision) and the F-14 Tomcat (in true Top Gun style, its pilot Mickey Simon wore a rakish grin). The A-10 Thunderbolt looked as chunky as its Zangief-like pilot Greg Gates, but it made up for its lack of style with firepower and durability.

But there was something strange about U.N. Squadron, too; something that felt slightly off-kilter. There seemed to be an underlying narrative to the game, a bigger story that players only glimpsed a tiny fragment of. This certainly wasn't uncommon for arcade games of that era -- Capcom was, after all, the company that brought the world the enigmatic Strider -- but it seemed unusually prominent here. And what was with the shop system, which curiously refunded you for unused special weapons after each stage? Why did the runway in the opening cut scene read "A88"? And who was this mysterious "DAIPRO" credited on the title screen?

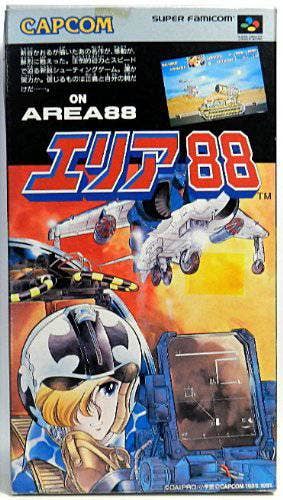

In truth, U.N. Squadron was a very thinly veiled licensed game... so thinly, in fact, that Capcom simply changed the name for the U.S. release. Shin Kazama and his comrades were all major characters from a long-running manga and anime property called Area 88, created by Kaoru Shintani -- hence the "A88" markings that appeared from place to place in the game -- and the game came over to the West with all names and references intact. The only major difference between the Japanese and English versions of the game, besides the language of the in-game dialogue, was the title. Why exactly the game's name had to change, but nothing else, is something of a mystery. By the time the game reached the U.S. in 1991, the manga had already been localized into English under its original title by Eclipse and Viz, so it's not as though "U.N. Squadron" was a prospective localized title.

Knowing the origins of U.N. Squadron goes a long way toward explaining some of its quirks. Despite the bolted-on title, the protagonists had nothing whatsoever to do with the United Nations; on the contrary, they were more akin to the Foreign Legion. Area 88 housed a squadron a mercenary pilots who operated under a contract obligating them to fly and fight in a semi-private turf war for three grueling years. Alternately, pilots could buy out their contract for $1.5 million -- hence the game's seeming obsession with tracking and refunding your earnings through the course of the story.

Anime-based game releases being distanced from their source material in the U.S. was hardly unusual in the late '80s, of course. Everything from Dragon Ball (aka Dragon Power) to Ranma 1/2 (aka Street Combat) was hacked and hidden, either to disguise the games' foreign origins or simply to reduce the obligation of license fees. U.N. Squadron, by comparison, seems like a demonstration of the least effort possible, like the time a kid in my second-grade class tore my name off my homework assignment and wrote his own name next to it. The teacher wasn't fooled for a second, yet my classmate feebly protested all the way down to the principal's office.

U.N. Squadron looks like it was ripped straight from the pages of Shintani's manga, regardless of what it was called or the hastily rewritten backstory. The inexplicable change turns a solid shooter into an odd little sidenote in video game history. Although actually, what's really weird is that Area 88's follow-up echoed the U.N. Squadron name change; since it didn't have the Area 88 license anymore, Capcom called it U.S. Navy instead. Well, that's what they called it in Japan, anyway; in America, it was bizarrely renamed Carrier Air Wing. So really, who even knows?

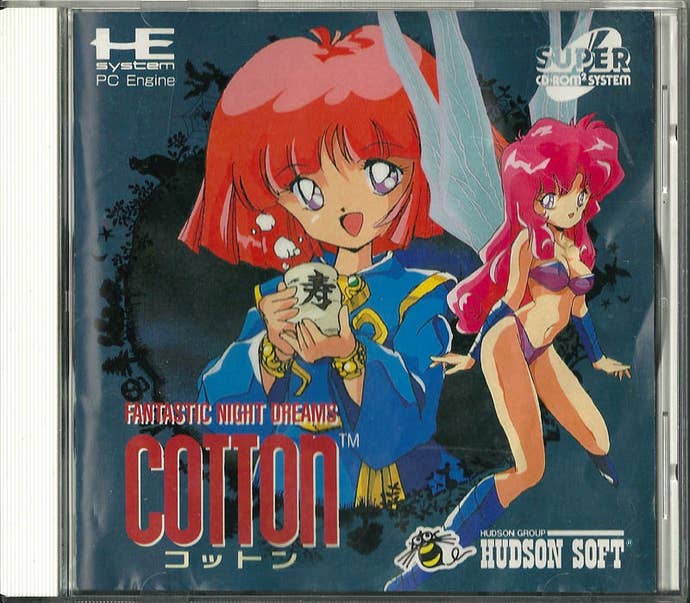

Cotton: Fantastic Night Dreams wins the Hearts

On very rare occasions, Americans have been granted a small glimpse into a game genre indigenous to Japan known as the "cute-'em-up." As you might gather from the name, cute-'em-ups are cute shoot-'em-ups. It's as self-explanatory as it is far-removed from the gaming American mainstream.

There are entire franchises of cutesy shooters that have never made their way to the U.S., most notably Konami's Parodius games. A parody of the Gradius games (geddit?), Parodius has been around for more than two decades, yet the closest we've ever come to a legit U.S. release for the series was the recent bizarre offshoot Otomedius, which replaced the lunacy and satire with sloppy mechanics and a sort of desperate, pandering sleaze -- sure, the shooting is awkward, but look at the girl dressed up as a half-naked Simon Belmont! Almost every shooter worth its salt has seen a cute, parodic, or super-deformed offshoot, even the noble Galaga (in the form of the wonderful Cosmo Gang: The Video). Yet you can basically count the number of cutesy shooters to have made it to America -- Fantasy Zone, Stinger, Ordyne, Keio Flying Squadron -- on one hand.

But few cute-'em-ups were quite as cute, or quite as seemingly unsuitable for manly American audiences, as Success' sugar-coated fantasy shooter Cotton: Fantastic Night Dreams... which makes the fact that it was actually localized all the more bizarre. After debuting in Japanese arcades in 1989, Cotton made its way to practically every non-Nintendo platform under the sun. And somehow, inexplicably, four years later, the Turbo CD version managed to escape the grasping gravity of Japan and ended up appearing as an English release.

Perhaps publisher Hudson was banking on sex appeal to sell the game. While there's nothing at all sexy about the titular protagonist, Cotton -- a childlike witch whose mop of pink hair suggests her name refers to cotton candy rather than the so-called "fabric of our lives" (TM) -- her faerie companion Silk features prominently on the box art, clad only in a revealing purple bikini. Of course, in-game, there's hilariously little of that to be seen; outside of the obligatory anime-style cut scenes, Cotton reduces its characters to chubby little sprites fighting against ridiculous-looking fantasy monsters, raging pumpkins, dopey-looking fish-men and so forth. Cotton isn't much larger on-screen than your typical tiny spaceship, and Silk -- playing the Option to Cotton's Vic Viper -- flutters around as little more than an abstract smudge.

No, there's not much sexy about Cotton, despite the cover art. It was a quintessential cute-'em-up, which means the entire affair was drenched in pastel colors and populated by utterly adorable enemies. Visually, it made for a striking contrast to other TurboGrafx shooters, which usually went for a darker style -- technological dystopia or biological horror, that sort of thing. Cotton, on the other hand, had to do with a witch who wanted to gorge herself on candy and was determined to shoot down every cuddly, chubby harpy that got in her way.

Where Cotton did resemble the rest of the TG16 library was in its difficulty, which didn't feel at all like you'd expect from a pastel journey through faerie-land. Apparently searching for willow candy is serious business, because Cotton faced off against some unflinchingly brutal challenges along the course of her journey. The power-up mechanics worked like a hybrid of the standard Hudson shooter system and -- fittingly enough -- Twinbee's bells. But the harsh checkpoint system and small stock of lives made for a shooter hiding vicious fangs beneath its willowy, pillowy exterior.

The Cotton series would go on to inspire quite a few sequels, including a technological marvel called Panorama Cotton that pushed the Sega Mega Drive to remarkable heights of 3D graphics. Eventually, though, the series fizzled out about a decade later in the wake of an uninspired Dreamcast chapter, Rainbow Cotton, though the protagonist did show up in Success' wickedly difficult DS strategy game Rondo of Swords a few years back. Despite its relatively short life, the Cotton series seems to have been remarkably influential. Developer Quest created a shameless clone called Magical Chase a few years after the original Cotton's debut; interestingly, the Witch-class characters in the Ogre Battle series look an awful like Magical Chase's protagonist Ripple. The Cotton format was also adopted wholesale by Victor's Keio Flying Squadron, which was slightly less obvious about its pilfering by dressing its young heroine in a bunny costume (despite its medieval Japanese setting). And then there's Touhou, a rabbit hole far too deep to be spelunked within the parameters of this humble retrospective.

Despite somehow making its way to the U.S., the original Cotton appears to have been almost entirely forgotten by American gamers. No doubt its being a niche release on a niche add-on for a niche console didn't really do its sales many favors (though it certainly has helped the game's aftermarket value). Still, it's a fascinating curio: One of the few instances of an oddball sub-genre to make its way to America. It's also an artifact of a very specific time, with its decidedly '80s anime look and attitude. In a lot of ways, the cute-'em-up died through commoditization, as the idea of selling hardcore game genres by dressing them up with scantily clad girls has become more or less the standard for much of the Japanese games industry rather than the exception -- though the relative restraint demonstrated by Cotton (only one female character appears nearly naked rather than all of them!) has long since disappeared.

Valis II attracts a small army of collaborators

For Americans who discovered anime in the early '90s -- say, after Akira, but before Evangelion -- the pre-import-boom days of exploring Japanese cartoons meant searching almost blindly for quality amidst shelves laden with cookie-cutter mediocrity.

In other words, anime in the '90s was a lot like anime in the '10s, except with two major differences. First, animation budgets were often insanely lavish thanks to the extravagance made possible by Japan's economic bubble throughout the '80s, so even if they were crap in terms of content those old videos at least looked stunning. And secondly, no one had ever heard of a "moeblob" back then, so the overall aesthetic was different. Fewer school girls, fewer meandering Azumanga Daioh knockoffs, more parity to western film genres. Sure, anime featured just as much borderline-tasteless exploitation of women back then, but the exploited women tended to be older and a lot less meek than they are now.

While that brand of boilerplate anime -- both tame and racy -- made it way to the U.S. in dribs and drabs alongside better-known works like Bubblegum Crisis and Tenchi Muyo (usually by way of ridiculously expensive video tapes that cluttered the "Japanimation" section in the dim back corner of the sleazier class of local video rental shop), it wasn't so common in games. You can't swing a dead nekomimi in a Japanese retro gaming shop without knocking over a few shelves of insipid anime-esque games from the '80s and '90s. And plenty of them feature adventuresome ladies in dangerous states of undress, boldly defying all manner of unsavory ends with sword or gun in hand. In America, not so much.

But at least we have Nihon Telenet's Valis games. Nowhere will you find a more perfect example of this particular niche of anime aesthetics than in the Valis games, many of which made their way to the U.S. courtesy of Telenet's long-vanished Renovation label. While they're not great games, in that sense they're actually kind of perfect: Utterly faithful renditions of the workmanlike anime and manga that inspired them. And while (like Clash at Demonhead) they tended to reach America wearing airbrushed Boris Vallejo-like Western-friendly cover art, inside they resembled 100% schlocky anime through and through, just like their original Japanese versions.

Case in point: 1989's Valis II. While the game appeared on several platforms in Japan, only the TurboGrafx CD version came West. Thankfully, it was a glorious rendition of the game. Crammed with slightly-animated cutscenes and the amateur-hour voice acting that characterized action anime dubs in the '90s, Valis II's story cutscenes had a running time nearly as long as the game's six brief, straightforward stages took to complete. Its connection to Japanese cartoons was as hard to hide as its generally mundane quality.

Not to say Valis II was a bad game; rather, it was aggressively average. It was your typical run-and-slash melee action game, a descendent of countless arcade titles like Rastan, Dragon Buster, and Magic Sword. And, much like Magic Sword, as protagonist Yuko grew in power she gained the ability to fling energy beams from her blade, progressively turning the adventure more toward the likes of Contra.

Alas, Valis II lacked the creative inspiration of Contra; its levels mostly consisted of flat ground containing a steady stream of monsters who would scroll into view as Yuko ran. While the adventure's later stages took on a somewhat more adventurous design, with moderate amounts of platform-hopping and even the need to switch scroll directions from time to time, its level design never managed to achieve anything more than "average," and its stiff controls and boss set pieces didn't help matters any. Its stages were like a journey through 8-bit visual design clichés: The quest took Yuko from city streets to otherworldly caverns to sci-fi techno-palaces to the inevitable bio-horror.

But despite offering fairly rote material, Valis II managed to win over a small but devoted American fanbase for being, well, uncommon. Even though Valis II represented a fairly uninspired slice of Japanese console game design, its aesthetics set it apart in the West, where such games rarely appeared. It was gloriously, unapologetically patterned after those exotic (and occasionally very graphic) cartoons that sometimes showed up late at night on cable or in the dustier corners of a video store. They were basically D-movie fare, animated equivalents of bottom-tier Hollywood Star Wars try-hards, but they were nothing at all like Disney or Saturday morning American cartoons, and Valis had the same intriguing luridness about it. Valis II brought Japanese animation into video game form in a time when Americans rarely saw such things. Add to that some of the most elaborate video game cutscenes ever seen to that point -- far lengthier and more detailed than Ninja Gaiden's! -- and some hard-rocking CD-based tunes, and it's easy to see the appeal of Valis II. Especially to the sort of tuned-in gamer who would have owned a TurboGrafx CD.

And despite being generally insipid, there were definitely little flashes of quality throughout the game. Yuko herself underwent several changes over the course of the adventure; while she began as a schoolgirl who stumbled into a mysterious power (a few years before Sailor Moon rendered such things a cliché), she soon geared up with increasingly complex forms of armor. Admittedly, they were all battle bikinis, but they provided fairly respectable protective coverage so far as such things go. Additionally, the power-up system offered a satisfying sense of player progression, and there were just enough differences between the stages to keep them from feeling totally homogenous. While Valis didn't set the world on fire with innovation, there was enough competent design behind its novel-for-us anime appeal to sustain interest in the game.

Later Valis games would build on the hints of depth and quality seen here, rewarding intrigued fans with welcome improvements. Much later Valis games, unfortunately, would take a turn for the crass; the Valis X games revived the franchise as an unflinchingly pornographic adventure series, taking the "sketchy VHS anime corner" spirit of the early '90s to its logical and graphic extreme. But tragic as the final video game indignities inflicted on poor Yuko turned out to be, it did at least make the flawed-but-decent older games like Valis II seem far better in hindsight. Like they always say: better generic than degenerate.

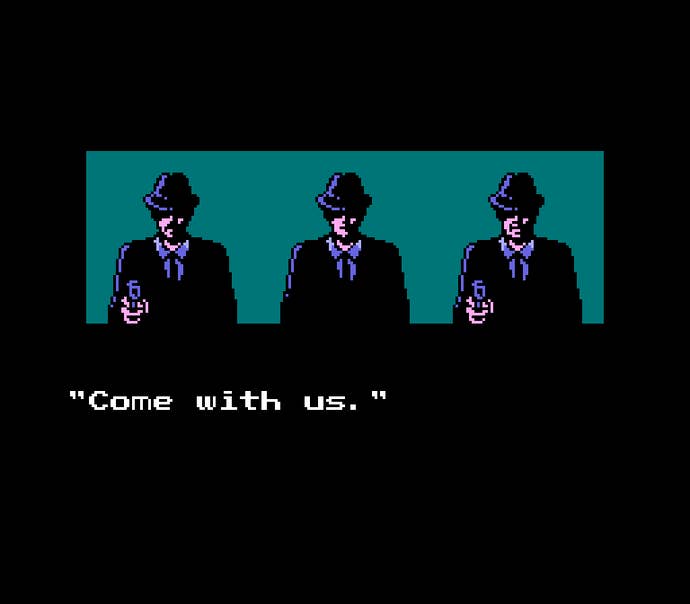

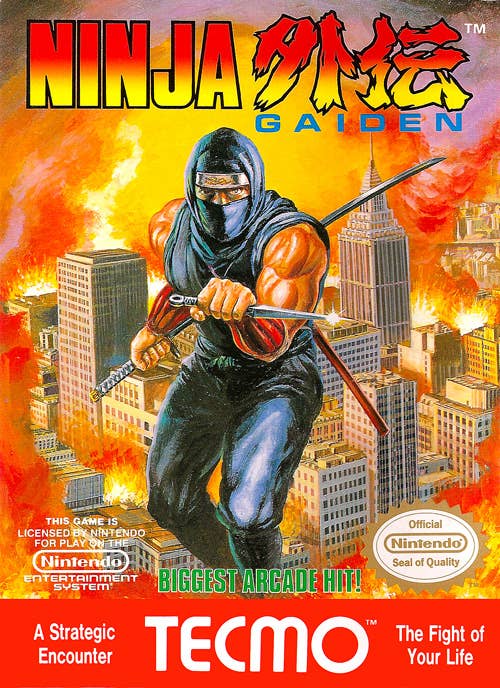

Ninja Gaiden wins the minds

"Just like the movie!" promised the ad for Ninja Gaiden, an upcoming NES game about, I supposed, ninjas.

"I wonder what movie they mean?" I wondered. I'd never heard of a movie called "Ninja Gaiden," though admittedly I was hardly a connoisseur of ninja flicks. I spent enough time at the local book-and-video store to realize there was a vast sea of movies out there, far more than I had ever heard of.

And anyway, I wasn't too excited about another NES game based on a movie or TV show. Those almost never turned out well.

As it turned out, though, someone had abused an article in that ad. Ninja Gaiden wasn't like the movie, because there was no such thing as a Ninja Gaiden movie (not yet, anyway, though the less said about the crummy anime that came along a few years later the better). Ninja Gaiden was more correctly like a movie, or rather a Japanese cartoon if you don't mind putting too fine a point on it. Somehow, within that chunky grey cartridge, the wizards at this company called "Tecmo" had managed to cram a ninja movie in between more than a dozen stages of fast-paced action.

Well, really, even calling it a "movie" is rather generous. Ninja Gaiden's cut scenes may have had cinematic aspirations, but in truth they were more akin to manga panels. In some of the more deluxe sequences, they almost resembled a very stiff and limited form of cartoon. But really, with their fixed angles, minimalist animation, and heavy black frames around the on-screen panels -- a space-saving convention that nevertheless created a convenient parallel to more familiar media -- Ninja Gaiden was a comic book you could play.

But hey, good enough. In 1989, that was pretty stupendous on its own. In the two years I'd owned an NES, the games had gone from shuffling around barely recognizable human forms to vivid tales of ninja revenge and demonic invasions. Wow!

In hindsight, yeah, Ninja Gaiden's story is pretty hokey, and the tiresome mansplaining of the plot prior to the beginning of stage 4-1 dragged on even back then. But you can't fault the game for its sharp aesthetic appeal, with dramatic camera angles and just enough animation to make static images feel lively and energetic. And, in true Castlevania style, the scenery reflected the story being presented: American Ninja protagonist Ryu Hayabusa went from being assaulted in a back alley to escaping a secret military installation to forging through the jungle and a system of mysterious caverns to take the fight to an ancient temple where Evil Awaited.

Also like Castlevania, the game action had a certain sense of rhythm to it that, once grasped, made its daunting difficulty feel considerably less brutal. Really, it was about memorization, but the whole thing flowed. Run, stop here, slash a foe, grab a power-up, leap to a distant platform and slash just so to take out the monster that appeared mid-jump. The enemy placement bordered on the unfair (and the way foes would respawn endlessly if you backtracked or even scrolled to certain spots made it worse), but the tight controls and helpful power-up placement meant that you could overcome the challenges -- and with enough practice, you could look slick doing it. According to producer Hideo Yoshizawa, that was precisely the point.

I admit, I have trouble looking back objectively at Ninja Gaiden, because it had such a profound impact on me at the time. My jaw dropped at its cinematic aspirations. I showed off the castle approach cut scene to all my friends. I played the game so much that I didn't just beat it, I could complete it without continuing -- no easy task given the wretched cruelty that defined the final battles. (If you died at any point in the three-part showdown at the end of the game, you'd be flung all the way back to the start of the game, a development glitch that the designers liked so much they kept intact, because they're bastards.) I used its sound check mode to provide sound effects and music for audio plays my friends and I created. I was a huge nerd, and nothing made me nerdier than Ninja Gaiden.

But in hindsight, I've also come to terms with the fact that, yeah, the game was hardly perfect. Even if you can forgive the nasty endgame gauntlet and the overly aggressive respawn rate, Ninja Gaiden has a lot of rough edges. The bosses seem daunting until you realize they use ridiculously simple patterns and can be killed without breaking a sweat; Ryu's habit of sticking to walls at inopportune times can be fatal; and many situations are designed in such a way that you need specific skills and weapons to pass them safely.